The Ellis Family

Intro:

The Ellis family members are only largely known as practitioners of weird and wonderful sounding concepts such as phrenology, psychometry, chiromancy etc at the turn of the 19th/20th centuries on the wide and exhilarating sea front of busy Blackpool on the west coast of Lancashire, UK. But there is much more to the story than that. They were both show people and entrepreneurs, being influential in the origins of the iconic Pleasure Beach, and they became very rich out of their endeavours. They never failed to argue and stand up for the genuine nature of their firmly held beliefs, and this led to fines, imprisonment and heated discussions in the local Council chamber when Albert Ellis was elected to represent the Brunswick ward of the town.

From their tenement building facing the sea on Blackpool’s Promenade and proudly promoting their name and their profession of ‘Phrenology’, the Ellis family was ostensibly a family of fortune tellers, palmists and phrenologists and other kinds of arcane ‘ologists’and ‘onomists,’ which they promoted in their literature. Through the years they advertise profusely in the newspapers nationwide and travel to trade fairs throughout the country.

However, looking back over the shoulder with this information only, perhaps with a patronising view of history, they could easily be considered the quacks, eccentrics or charlatans which invited the contempt, ridicule, fines and imprisonment, (Ida spent a short time in Preston Gaol) that they were subjected to. They are nevertheless part of the Showman World and Blackpool was the place for them and, if you consult the records, they allow you to open the door of the property and take a peek inside, and then a very different, and much more complete and sympathetic story emerges.

They weren’t alone in preaching and practising subjects which are generally beyond the pale of conventional learning and understanding and which to them was all part of the progress towards understanding, explaining and presenting, even attempting to cure, the human condition. Taken seriously it could be considered as a science and, to the Ellis family, it was just that. At the same time, and forever and a day, there are plenty of folk claiming to possess the palliatives, or even answers, to the human condition for a price, selling this, that or the other advice. There were many off-beat beliefs and practices, where there was a potential, captive audience to convince, and from who to extract a sixpence or two, and Blackpool provided just that opportunity. My grandfather expounded the Christian Faith via the Plymouth Brethren from his little booth by the Promenade. This was in the 1930’s when Frank Ellis would have still been practising round the corner on the Promenade. I don’t know how many people took my grandfather seriously, but life was already too serious and difficult in the big cities from which the majority of those who streamed passed, and who had escaped for the short but explosive freedom and a breath of fresh, breezy air that the week in the town provided.

The distraction of life outside seriousness and despair which Blackpool could provide in great quantities was more in the mind of the day tripper or extended holidaymaker. Many would be heading for an impulsive and ineluctable life changing experience under one of the piers (referred to with laughter in one the heated exchanges in the Council chambers between Councillors Bickerstaffe and Ellis). But then, somewhat eccentric on the outside, my grandfather was nevertheless a man who had amputated many a limb from a screaming soldier who had been carried to his medical tent on the Western Front and he probably realised that the salvation of humanity to rescue it from its savagery, was beyond the capability of the miserable human being, and the answer had to lie somewhere else. In that sentiment there is a tenuous parallel to the Ellis Family. It was a new way of looking at the science of hope. They thought they may have found a method of improving the human condition for one and all, and pursued it thus.

A contemporary of the Ellis’s was Dr George Kingsbury whose innovative methods of hypnosis worked for his patients but not for those who were opposed to his ideas and who didn’t want to believe in them. He had won a libel case concerning his practices earlier in the 1890’s and he was up before the magistrates again in 1899 because he had allegedly hypnotised a rich woman, his next door neighbour at Brighton Parade, into including himself in her will. It was her son who contested the £30,000 left to the doctor but the case was found in Dr Kingsbury’s favour. In between these dates he had been Mayor of Blackpool and he had been practising in the town as a doctor for about 15 years. The Ellis’s had practised both hypnotism and mesmerism before coming to Blackpool.

The lives of the Ellis family, Albert, Ida and Frank, don’t reveal people out to make a quick buck from vulnerable people. They made their money through the entrepreneurship of land and property. Looking beyond the weird and wonderful sounding profession of Physiognomist, into Ida’s sensitivity and Albert’s political Liberalism, it can be revealed that they showed compassion for the human condition expressed through the serious nature of their firmly held belief in their subject and its high sounding companion descriptions.

It could be seen as a story of Liberalism versus entrenched Conservatism, equality versus privilege, equitability versus prejudice and tolerance versus intolerance played out in the Council chamber, the sands, the fairgrounds and the substantial tenement buildings of the Ellis’s property in the town. Though it was largely a lone battle they fought in the town, they weren’t alone in their ideas and the claim that the character of a person could be determined by the physical features that the body possessed either in the shape of the head, (the ‘bump feelers’ of Councillor Bickerstaffe’s cynical retorts), the lines of the palm or the features of the face, had the considered attention of many people of letters and status. A reading of character, or advice on the future of love and happiness through these features would be given through a personal appointment, face to face or through a photograph at the confidently advertised address, first on Kent Road, then more prominently, on the Promenade. You could send an imprint or a photographic image of the hand which was a good substitute for the real thing. After all, we are all seeking knowledge of self, or those that don’t would probably need to, and if there was a simplistic and confident method of gaining that knowledge, like walking into a palmistry booth, rather than the complexities of laying for long sessions on a psychiatrist’s couch, or thorough the natural pain or exhilaration of finding it out through a life experience, we all probably would – and should. The price of this consultation at the turn of the 19th century into the 20th, was 1s (5p), which, using an online inflation calculator would be equivalent to a little over £23 today.

The Ellis’s had arrived in the town from Leeds in 1893, when the Town Council in Blackpool was becoming increasingly concerned about the proliferation of such practices on the beaches. From here, albeit after a bumpy ride, their practice flourished and they also resumed the publication of their work in several booklets on the various subjects they preached, mostly written by Ida and published by Albert. They also trained others in their methods. They believed entirely in their subject and were protective, sometimes nobly so and sometimes perhaps jealously so, of their command and understanding of it. There are many extant publications of the Ellis family, some available on Ebay, some in family possession, a publication of Frank Ellis’s at the Wellcome Library and some in the Blackpool Museum.

There were three people notably involved in the family business, husband and wife team Ida and Albert, and Albert’s younger brother Frank when he came to join them. Ida and Albert had a son Frank, who left England in 1913, arriving, perhaps appropriately, at Ellis Island, New York in that year. By 1939 he is a colonial solicitor and working in British Honduras – now Belize. On the 1911 census he is in digs in London and working as an articled clerk, eventually to become the solicitor he was training to be. In November of 1913, Ida states, clearing up the query that the Frank at the premises in Blackpool is not her son who was involved in the family business, but her husband’s brother Frank, employed by the family, and that he is ‘out of England, eleven months since’. At one time Annie Isabel Ellis, a cousin of Albert’s (a widower, an uncle, Albert Ellis 67 years old, born in Canterbury, and daughters Clara and Annie were living at Louise Street, Blackpool in 1911) was at the home address for some time, thus persisting in close, family ties. Another brother of Albert’s, Walter Henry also came to Blackpool and there are living descendants in the town today.

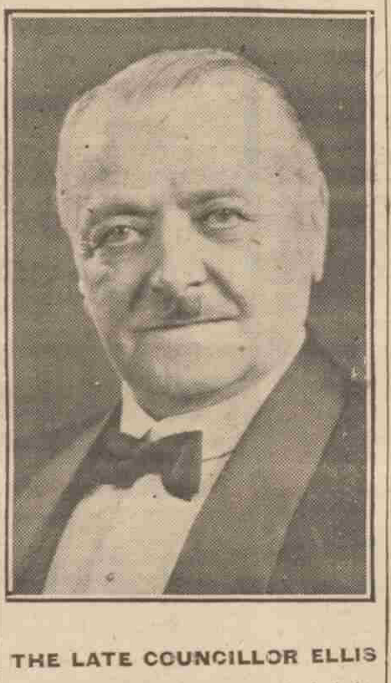

While Ida and Frank, her brother in law, were largely the practitioners, Albert was the businessman who was also elected to the Town Council and had many an interesting and unflinching conflict in the Council chambers with his arch enemies, Aldermen Grime, Bickerstaffe, Fish and Briggs, who were contemptuous and derisory that a councillor in their elitist group should have a connection with such a common enterprise as palmistry, even when the bigger word of phrenology (or ‘bump feeler’ as described by Alderman Bickerstaffe), was used. For Albert, his scientific approach to truth brought him into the conflict of the protocol of the Council chamber and he can perhaps be seen to be naive in the way he presented himself in his arguments, though not necessarily in the truths his statements. Words and sentiments like ‘liar,’ ‘bully’, ‘white livered devil’ and ‘white livered scoundrel’ crossed the Council chamber like tennis balls, one volleyed back to the other and they were challenged to meet outside the Council chamber to settle their differences as often is the only way the male animal knows howto settle differences to the eternal misery of others who have to take the consequences. As a businessman, this ‘unbearable’ irregular outsider, Councillor Ellis, was as successful as any of his Council members, and dealt in land and property and he eventually had neighbours on Lytham Road, living next door to Frank Pennington, founder of Arnold House School and next door but one to William Bean, creator of the Pleasure Beach, and also a rival in business of his.

There also appears to be a mutually sympathetic association with renowned historian Allen Clarke who, in his spiritual phase, might have found a common thread with the Ellis’s as his book ‘Knobstick’ originally published in 1893, was republished in Blackpool by the Ellis’s in 1906.

The Ellis’s weren’t Blackpool people and, though their last known previous addresses before arriving in the town were Batley and Leeds, where Ida was a practising phrenologist and Albert was an insurance agent, they were not native to that town or city. In 1891 they are described as travelling phrenologists and it was possibly for this reason that they first arrived in Batley or for Albert’s opportunistic work reasons, or perhaps again, for the birth of their son. They were there for a couple of years and while there they were both connected with the Salvation Army (and continued that support in their eventual move to Cornwall) which would have encouraged their desire for change in the sad condition of the human being, and they might succeed if they could find a way scientifically. They would have liked to have stayed in Batley (she was well remembered in the local newspaper report of her subsequent fine and imprisonment at Blackpool in 1904) but had left by mid December 1892 ostensibly to premises in Leeds more suitable to their ‘country’ patients but also possibly due to their published book being classed as ‘obscene’. Their stay in Leeds didn’t last, and a glance at google earth doesn’t present a picture of the most salubrious of areas today, and eventually Blackpool would provide much more opportunity they hoped, and it did.

Ida Mitchell was the daughter of a farm labourer from the little village of Alpheton in Suffolk and Albert and his brother were sons of an artisan whitesmith from Wincheap, Canterbury and were working from an early age, Albert as an errand boy at 13 years old. Albert, according to one census return had lost his right leg, assumingly in an accident during his youth. Ida disappears from the 1881 census but at 16 years of age she was probably in service somewhere. There are promotional pictures of the Ellis family in their instructive publications, and in one, Albert is showing his hand to Ida for her to read. His left leg is prominent but his right is hidden behind the voluminous and strongly feminine, all-covering, floor reaching dress of his wife. The boobs and bottoms, or even budgie smugglers of a Blackpool or a Bondai Beach are there to excite the libido and don’t make good subjects for serious character reading, being more akin to the behavioural sciences. Ida was a strong personality and her femininity transcended the mere physical. There is a reference to Albert’s physical disability in his obituary, though it is not stated what it is but it is something he bore with great dignity, it is reported, and it hadn’t hindered his success in life.

Ida had a vision for her life, and she was confident in it. She did not traditionally become a mat weaver, in coconut or horse hair, or a horse hair drawer or other subsidiary work involving weaving, as several of the Mitchells and other families were before and after her in the tiny Suffolk village and immediate environs of her birth. She was both energetic and articulate and though a Victorian woman who was obliged to accept her place, her first meeting with Albert wherever that might have been, created a union which was greater than the two individual parts put together. They were perhaps made for each other. Perhaps their head shapes were immediately compatible and behaviour, was just subject to that and was nothing to do with previous experience of character formation… Whatever way, she knew he was right for her and she for him.

Albert and Ida Eliza married at St Mildred’s parish Church in Canterbury on the 24th June 1889 and it seems a cousin of Ida’s was a witness. Kent is only across the estuary from Suffolk so it is not unreasonable to assume that the Rosa Alberta Mitchell who lived in Canterbury was the Mitchell who signed as witness and was related to Ida. Albert and Ida in each other appeared to have found a kindred spirit, strong and long lasting and bound themselves together in this way.

So, by 1891, with their one year old son Frank, Ida and Albert are living in Batley and presumably had been there at least for a year as Frank was born in the first part of 1890. Ida describes herself as a phrenologist while Albert is an insurance agent. While phrenology was a hobby at first for Ida it later became her profession and this was probably with the help of the business vision and energies of Albert and their ideas and personalities combined to achieve success. In their time with the Salvation Army they would have seen, with the human subject matter of their attention, some of the unhappiness in life in others that they later tried to understand, or even cure, through a method of practical and attempted scientific analysis.

Having moved to Blackpool, Albert’s energy in insurance and land and property dealing eventually created their wealth and he became a town councillor, elected for the Brunswick Ward. His spirited debates with bitter rivals Bickerstaffe and Grime make interesting reading, especially when he had been accused in public life, of hiding behind his wife who took all the flak for his claimed profession as phrenologist.

With their eventual success, they moved to the more salubrious area of Lytham Road next door to Arnold House and they were resident in London for a while but still retained properties in Blackpool as ratepayers. They took a trip to India, in 1925 and continued on to Sri Lanka (Ceylon), Africa and Europe before returning home. Albert later gave talks on occasion during his time in Cornwall on this subject of travel, the Indian part significant in that it probably reflects back to their time in Batley. In 1930, they retired to Trewinnard House at St Erth in Cornwall. Albert died in 1934 and Ida in 1940 at that address. Albert left more than £70,000 to his wife and Ida left her £30,000 to her colonial solicitor son, Frank. Son Frank and family were living at Trewinnard House with Ida in 1939, shortly before her death, and no doubt Frank would have naturally inherited the Manse.

Albert’s brother Frank died late in 1939 in Blackpool. He was a bachelor all his life. There are descendants of the wider, Canterbury, Ellis family in Blackpool, Australia and I think the USA.

The Story.

Albert and Ida’s son Frank is born in the first part of 1890 in Batley, so it can be assumed pretty well that they had been there for some time previously. They had been described as travelling phrenologists and it may be that they decided to initially rest a little in Batley due to the birth of their son before moving on. The Ellis’s are first recorded practising in the town in 1891 and are found on the census return of that year. Ida advertised in the regional newspapers from a permanent address at 115 Taylor Street in the town where they had an established residence. Here she describes herself as a Professor of Phrenology and a Member of the British Phrenological Association. Albert had founded the British Institute of Mental Science in this year it is claimed, Albert and Ida are also founders of the Universal Phrenological Society. Seeing the value of the human being in intrinsic intelligence rather than privilege and wealth, her promotional theme was to ‘Go at once to Madam Ida Ellis…’Why work in the mill as a weaver, when perhaps you have the brain and talents of an Eddison, a Talmage, or a Gladstone.’ If you couldn’t get there in person you could ask for a copy of one of the instructional manuals to be posted for a price. A source of twelve private phrenology lessons cost £1. Ida of course, had left her life as a potential weaver, though as a cottage industry rather than a mere, impersonal unit of labour in a dark and dangerous, satanic mill, and was exercising fully the potential of her own character and personality. So success was open to anyone else who could be shown their potential.

It seems that they were happy in Batley and would have stayed except for the fact that they had their first brush with the law in 1891 after they had been in the town a little more than a year. They had been accused of writing and selling obscene literature but the obscene of yesterday is not necessarily the obscene of today and the content was concerned with family planning in light of the human misery of the poor and especially the women who had to prolong poverty and invite death by giving birth to numerous children with little access (and usually no access, since the man would not be likely to desist) to birth control. As members of the Salvation Army while in Batley, they would have come across the poverty that their science was constructed in an attempt to teach to avoid. The content of these books had the acquiescence of many ‘men of science’ and Albert in his defence, spoke eloquently, firmly and confidently before the Borough Court for the town. But despite his clear plea the case was found against them and though several copies had been sold, the order was for 2,000 copies at the publishers to be destroyed.

Their work had been described as of the nature of Annie Besant and Charles Bradlaugh who had controversially published work on birth control and which was considered obscene. Annie Besant had eventually formed the Theosophical Society in Madras, India which might explain why the Ellis’s went to India in 1925. As a kind of pilgrimage I suppose, and with the potential for meeting her there. They were of like mind in their fairness and their compassion for the human being though Annie Besant was perhaps tinted with a little bit of eccentricity in the later years of their meeting. ‘There is no religion higher than the truth,’ a great sentiment of the Theosophical Society, of which she was president for a while, though the truth can often be relative or prejudicial. She was liked in India, she was pro-independence and had a district in Madras (now Chennai) named after her.

The Ellis family had arrived in Blackpool sometime in 1893. The last seen advert in the Batley newspaper is the announcement of their imminent move to Leeds in December of 1892 and the first advert from their Blackpool address in Kent Road is late 1893. From 1893 to 1897 Ida Ellis publishes herself in all the regional newspapers in England, Ireland Scotland and Wales with the address in Kent Road, and then the adverts stop and she seems to go on tour with Frank, who has now joined the duo, as impresario manager. For Albert, someone who earned his living selling insurance (his claims on the census return of 1891 and 1901) the idea was to quite sensibly make a science out of all the onomies and ologies connected with what is generally understood as psychology and psychiatry today. They were big and obscure words and maybe through the mystery of these long and high sounding words that could be spoken by a few enlightened people, mostly men, and the arcane truths they might be hiding, they could open up a door into the confusing and anxious nature of the human psyche for all those attending the potentially healing or revealing sessions that the Ellis’s provided. It was more than just fortune telling. It was a science, and perceived to be at the cutting edge of reason, it was an attempt to resolve the complex nature of the human individual and open up a path to a better life. To make money out of it was perhaps incidental, but not the full purpose, and it’s only what qualified counsellors and psychiatrists do today. After all, for all the big words that described the practices of the Ellis’s, that very small word ‘God’ which, in its myriad forms had countless worldwide followers, depended on belief which doesn’t work for everybody and could be construed as being equally irrational and relative in bringing contentment via justification to the existence of the human individual. You didn’t need an answer since it was given on a plate to you. You just had to believe, which can be justification enough if it works for one and all without inviting the conflict that it does. So not much different to the path that the Ellis’s were taking, though there is no evidence that they were atheists.

But Albert Ellis and the family, were not just about arcane subjects, it was about human politics, Liberalism versus the entrenched self-interest of the town’s Conservatism, populism versus elitism, justice against injustice and the acceptance of others against the institutionalised denial of their human rights by those in authority. However, it was of course quite acceptable to make a lot of money out of land dealing and property along the way. He was around when Keir Hardie spoke in Blackpool but perhaps Albert’s Liberalism didn’t extend into the values of the emerging Socialism.

So, from late 1893 Ida Ellis was advertising from premises in Kent Road Blackpool, and which appears to be No 10 (from a newspaper report of Frank Ellis’s court appearance.) Today, conferring with google maps this is now the Deneside Guesthouse. For the price of 1s (5p) the character of a person, both in talents and failings, could be determined by the evidence of a photograph or handwriting. By 1894 Ida, as Madame Ida Ellis, is advertising in both the Stage and Era publications and eventually includes an instruction booklet on how to read character through the physical attributes of head, hand and face. An illustrated booklet cost 6d (2½p). In 1895 and 1896 she continues to advertise monthly in many of the regional newspapers. By 1897 the newspaper advertising promotions decrease and instead she has published ‘A Catechism of Palmistry’ and found a London Publisher in George Redway. An illustrated book, it is described as ‘The Sciences of Chirognomy and Chiromancy Explained in the Form of Question and Answer’ and cost 2s 6d (25p). It contains ‘answers to over 600 questions on Palmistry by the well known expert’. By 1900 Ida was advertising her speciality as being able to determine the potential of children and was available for consultation at Ribston Hall in Gloucester in December of that year. The Ellis family are advertising their address at 33 South Beach Blackpool in this year.

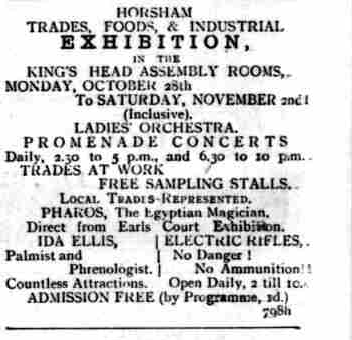

In 1907 she is seen to be back on the road and in October of that year she appears at the Horsham Trades Food and Industrial Exhibition.

Their first brush with the law in Blackpool came in 1894 when ‘Professor’ Frank Ellis was brought before the magistrates for fortune telling on the sands, that he ‘unlawfully did use certain subtle devices by palmistry to deceive and impose upon Caroline Baswell of Preston’. There are various spellings (or mis-spellings) of Caroline’s surname and it wasn’t her that was the prosecutor. Somebody else wanted to get at him. He had charged 6d for reading her palm. His address was given as No 10 Kent Road, one of the premises that the Ellis family kept for some time so it seems. The charge was quashed. The defence represented by Mr Callis quoted the answer to a question put in Parliament, that unless it could be shown that there was an intention to deceive then there could be no conviction. Palmistry was considered a science and not fortune telling therefore it could not be construed as an offence. In June of 1898 however, Frank Ellis was fined 40s (£2) and costs for blocking the footpath in front of his premises on South Beach while he was practising phrenology. There were gardens to the front of the properties on the Promenade before the road widening took them away so it can be imagined that Frank was in the garden and a crowd had gathered outside on the footpath, thus restricting the continuous flow of promenaders at the busy parts of the day that way. Fortune tellers and character readers had been removed from the beach and at one time Albert had a stall on the Central pier, but it hadn’t taken his vision long to establish premises in a more prominent position on the town’s sea front and he bought the premises on Central and South Beach in the town after being harassed off the beach with his trade in that year. Frank, a bachelor all his life, rented a furnished, ground floor bedroom at 82 Central Beach from his brother there which cost 10s (50p) a week round about 1910.

Never far from controversy and protective of their business idea, the Ellis’s were back in action the following year, this time on the offensive. In 1895 Joseph Palmer, a former pupil of the Ellis’s, went out on his own on the sands. Palmistry and phrenology was a lucrative business and the stands on the beach were always well patronised and £10 a day (over £1200 in buying power at today’s prices) could be earned, as alleged by the police. He thought he would be onto a good thing and he hung up his sign, acquired from and signed by the Ellis family (who he referred to as ‘those people’), proudly and confidently in front of him. However this upset the Ellis family as he had been trained by them and issued with a certificate of phrenology from the Institute of British Mental Science which Albert had founded in 1891. In unwelcome competition he had set up as a rival with their own copyrighted methodology. ‘Mental’ of course has somewhat pejorative connotations today and the ‘mental’ arithmetic of long gone school days has been replaced after the evolution of the word changed its meaning. The Ellis family had warned him to take it down or, he claimed, they would use foul means if he didn’t. The outcome was that the sign disappeared anyway and he asked the courts to search the Ellis’s premises on South Parade, because he assumed that they had stolen it. Though it had been signed by the Ellis’s, there was no signature of examination by Dr Brodie (I assume here that Dr Brodie was the same Brodie, town surveyor), which made it invalid and the request was thrown out.

The Ellis’s continued to advertise character reading from handwriting or photo for a fee of 1s (5p) at their address, Promenade Blackpool but in the later part of the 1890’s, Albert had acquired an interest in a fairground at South Shore and this gets into the industry publication of theatre and entertainment, the Era.

n 1898 the executive of the Van Dwellers Association, a national association of showmen (and women of course, but 1898 is still Victorian), held meetings around the country concerning laws that had been passed earlier in the year which alarmingly allowed Local Authorities to pass bye-laws at will and without consulting those who it might affect. In the case of the van dwellers, the travelling showmen, this would severely restrict them in their work. They could even be evicted without warning and without knowing whether they were doing right or wrong because the authorities had no need to tell what was right or wrong in the first place. It was cloak and dagger stuff for the authorities to get their own way without being laboured with discussion or consultation.

And the case of the Ellis family was brought into the argument and published in the entertainment paper, the Era. It was the Blackpool Building bye-law case, a case which was waiting to be heard at the Court of Appeal. Albert Ellis, and indeed Ida, were no push-overs when it came to defending their profession and would not give in without a considered argument. The year previously they had been driven off the sands for practising ‘palmistry’ and had acquired their two, sea front properties in the front garden of which they had erected their temporary advertising stand. (It seems large enough to fit two persons within for a more private consultation). This the Borough surveyor equally objected to. The laws were defined to protect the safety of individuals and temporary structures like the tents and huts of the van dwellers and the show people involved needed to be regarded as safe, a necessity which in itself cannot be argued against, and the paper agreed. However the paper, in the cause of the numerous and varied show people throughout the country, accused the Blackpool authorities of twisting the bye laws to suit their own unstated design when they asked the Ellis family to remove their ‘temporary’ construction from their own front garden. It was on private property. It was one thing for the Council to legislate on the sands, but on private property it would invite expensive litigation for show people and Councils alike if a traveller couldn’t even put a peg in the ground without it being regarded as unsafe and inviting a summons issuing like a grand fountain from it. The whole professional lives of these people and their seasonal shows anywhere in the country were at risk.

The South Shore fairground was a popular place and would eventually, largely evolve into the Pleasure Beach. The Era of June 1898 has this to say about it, ‘The seaside resorts, like the fairs, have felt the full effect of the adverse weather. They all with consent (except one phenomenal exception) tell the same tale – ‘’bad, bad.’’ Blackpool South Shore fairground contains the following novelties; The ‘American Carousel’ (a roundabout-machine with horses, camels, lions, and other animals in tether), the Hotchkiss patent bicycle track, a switchback and other machine novelties, drop boxes and slot machines, a Russian fur stall and a fruit kiosk. A prominent feature on this ground is the splendid van of Messrs Grange and Sons, the well-known ‘Little Wonders’, purveyors of the celebrated ‘Blackpool rock.’ Here, too, are the consulting cabinets of the Ellis Family, the psychometrists, and Madame Vane, the palmist; the photograph studio of Mr Taylor, George Richardson, auctioneer etc; a stereoscopic show, with views of the war in Cuba; and the crowd of small novelties organised by Messrs Rossington, Twigg, and others. The change this year in the order and date of the holidays in the large Lancashire towns (Oldham to wit) has kept the biggest crowd of visitors until the end of the week. Though this has been deeply lamented by the show people of Blackpool, yet on the whole it may prove a blessing, for had the people been with them the rain would have spoiled the market.‘

(The Cuban War refers to the Spanish-American war of that year in which the American victory wrested much land off the Spanish. It not only annexed Cuba but many other territories including Indonesia.) (Wikipedia.)

Another report on the fairgrounds reveals that at Blackpool there had been a record Easter where the Ellis family, ‘character readers, hold public demonstrations on the fairground.’

There is a photograph of the Ellis practising on the beach at South Shore in which there is a large crowd gathered round and focusing its attention on the activity at one end of a marked off area. It appears to be a demonstration or instruction and there is a triangular tent which you would be expected to be used for any private consultation to anyone convinced enough by the promotional skills of the speaker.

But the Council weren’t finished yet and in the following year of 1899 the Ellis’s were once more in deep water for breaches of the building regulations concerning their land at the Fairground in South Shore. There were twelve cases to consider and largely concerned with the safety of the constructions of some of the huts being built of combustible materials. A coconut shy for instance, was built of wood with a canvas roof covering and it was considered unsafe. The attendants had been warned to take the roof off but hadn’t complied. The defendants, in this case, Albert, Frank and James Ellis were fined (50p) and costs in one case and 5s (25p) and costs in nine other cases on their land. I’ve not been able yet to positively identify James Ellis.

In 1901 while Albert is away at Huddersfield as an insurance agent, Ida, her son Frank and Frank her brother-in-law are at the address of 33 South Beach and living next door to Christopher Irwin, manager of Madame Tussaud’s waxworks. Both Ida and Frank are described as character readers. Here the family could afford to maintain a house servant.

But he was only away briefly on business for Albert Ellis with an address at 33 South Beach advertised land for sale at South Shore suitable for Stalls, Shows, Roundabouts etc and land was always at a premium. Albert and Ida would eventually become a neighbour of William Bean, popularly regarded as the founder of the Pleasure Beach, on Lytham Road. Nick Moore has the Blackpool New Fairground Company Limited, a rival to the Pleasure Beach, created and owed by Albert Ellis. There was controversy in the Council chamber in July of 1907 about the large number of temporary buildings allowed on the fairground site which appeared unfair to those people in the town who had to pay rates on their permanent buildings.

In 1902 the life of Albert Ellis, phrenologist and publisher changed as his candidacy for Councillor was accepted for the Brunswick Ward. He was subsequently elected and his name is frequent in the newspapers from this date until he chose not stand for a seat on the Council any more around the end of the decade.

The following year Albert was putting out fires not in the Council chambers but in the next door property at Seymour House at South Beach. The Ellis’s discovered a fire which, on investigation, was coming form the next door premises. Quickly calling next door Frank and Albert were able to put out the fire which was under the floorboards and was burning the floor joists away. They had used a hosepipe and a disaster was averted without the need for the fire brigade.

In September of 1903 Councillor Ellis was once more engaged in crossfire with Councillors Grime and Bickersatffe and was largely unmoved by their accusations and insinuations, giving as good as he got. The Watch Committee wanted the Spiritualists off the beaches, objecting to them meeting there and promoting their beliefs. Councillor Ellis was on their side, sympathetic to the right of their particular beliefs, as much as he had a right to practise his.

In 1904 both Albert and Ida stood up to be counted for their beliefs and both demonstrated their loyalty and their resoluteness to their ideas. First, Albert walked out of the opening ceremony at the Revoe Library in July of 1904 because the waiting public would not be admitted until 5pm. It was a public library paid for by the ratepayers, and the invited guests seemed to be keeping themselves apart from the working class rabble that was perceived as Revoe. It was the Ward that Councillor Ellis represented and his Liberalism, while it allowed him to make lots of money, would not allow for the perceived snobbery of the invited guests inside. Outside he told the people exactly why he had walked out, after all they were the people who would hopefully vote him in next time.

But it was in August of 1904, when the antagonism burned fiercest. Ida was brought to the Magistrate’s Court for practising the illegal craft of palm reading. She was in the company of several others, all stung by police action. The charge was that she, ‘did unlawfully use certain subtle means to wit, palmistry, and imposed on certain oh His Majesty’s subjects, to wit, John Leaver and Thomas Luke, two police constables of the Blackpool force.’

Those people arrested and with who both the Council, and consequently the police, had an equivocal relationship (they were good for tourism but nevertheless their practices were illegal) included Mrs Dearden Smith of Clare Street South Shore, Professor Vane who had a tent on the sands at South Shore, Madame Lozell of the Blackpool Palace and Bianca Unoma of Stanley Street who conjured up communication with the dead through her contact spirit guide Loo Loo, (Lulu) whom she described as a ‘little negro’ and who had warned her of the visit by the police two weeks earlier. She could immediately tell they were policeman by their feet when they entered her premises. Perhaps only a policeman could have an explanation for that.

Fortune telling was illegal and its practitioners were breaking the law, but the gypsies, most frequent exponents of the craft, were an attraction and brought many a tourist and day tripper to the town so what do you do with them? Occasionally you had to prosecute but mostly they were treated with a fair, blind eye. You had to since it couldn’t stop it. Ida’s arrest was due to the police sting of the 13th August. At that time the Council wanted to ‘harass and imprison’ fortune tellers, and often did their best to get rid of them.s’ . The legal defence had insisted on this occasion that Councillor Grime who had uncompromisingly referred to these people as ‘humbugs, frauds, rogues and vagabonds.’

The charge was under the Vagrancy Act of 1834, and the wording of the Act conveniently applied to the resident ratepayer, working from home, that Ida was on this occasion. The offence was that she was an imposter pretending to exercise power by claiming to predict the future by means of palmistry. She was accused on four separate counts.

Two police constables had visited the premises on South Beach and the first, constable Leaver, was charged 2s 6d (12.5p) and constable Luke 1s 6d (15p) for a palm reading. The results were written in a book which was given to the client. This book advertised further reading for more detailed advice at a cost of 10s (50p) and sent out by post. In these consultations, the other paraphernalia on offer and sale at the premises, like booklets on specific advice and subjects or even a crystal globe, were offered the client and could be obtained from Mr Ellis for 5s (25p). Each part of the booklet that was filled in cost sixpence. You could send someone’s handprint by post (for which the Ellis’s had developed a special ink, ‘transferine’ for that purpose). The court proceedings produced much laughter as the incredulity of the evidence was given by the prosecution. Ida would have had to sit through this and take it on the chin which she did with dignity and proven loyalty, both to her profession and her family.

The advice given at the consultation was read out in full by the prosecution. Constable Leaver was told that he had healing powers by the accused, Ida Ellis, at which the prosecutor, playing to the crowd who were on his side, exclaimed, ‘what trashy nonsense’, for which language he was admonished by the chairman. The prosecution had to prove that Ida had ‘intent to deceive and impose’ and then she would be guilty under the Act. The Council had a duty to protect the vulnerable, of which women and servants (outrageously condescending) were the larger part, and the problem of palmistry was becoming rampant. There was also the possibility that Albert’s political rivals had it in for him for he was now a Council member representing the Brunswick Ward and he would be accused of hiding behind his wife’s guilt.

Ida’s defence claimed that fortune telling unless it could prove to be dishonest or an imposition was not a crime. She had been in the business for fourteen years by now. Many men of letters believed in such things and just because members of the Council didn’t, it didn’t represent a crime, and just because they didn’t have the power or the vision, it didn’t mean that others hadn’t. When it was Ida’s turn to give her story it seems that the policeman were insistent and demanding first for a private room which she declined and then to get it over as soon as possible, no doubt to collect the incriminating evidence as quickly as possible and dash off to their superiors with it. There were several levels of consultation defined by the prices of 6d (5p) in five increments up to 2s 6d (12.5p). They took a shilling’s worth and she filled in two pages of the booklet for 6d each to make the shilling. Ida was able to eloquently defend her belief and did not desert the faith in her science. She was fined £25.00 and 2 guineas costs for some of the several specific charges brought against her and the other charges would be deferred to Nov 7th on the undertaking that she would discontinue the practice and take the advertising notices out of the window of her premises.

All the defendants were summarily dealt with, with the maximum fine of £25 with the undertaking that they would discontinue their practice or face 3 months in prison. Bianca Unoma opted for the three months in prison. There are several spellings of her surname, misheard or typographical errors. On the census returns the gypsies are anonymous, their names are not included, just their ages.

They did come before the court again, for in the November those cases that had been adjourned as to the undertakings of the defendants to end their practices, were held. Ida Ellis, Madame Bianca Unoma, Professor Thomas Vane (actually Henry Musgrove from Oldham), Madame Ariel (Frances Hawkins), Madame Elvira Dixon, A Mona (John Victor Green) and a Madame Edith Roselle.

Ida Ellis was first up again and the prosecution stated that the offensive signage regarding palmistry had not been removed from the frontage of the premises on South Beach. Ida was not perturbed and she was a lady not to be moved. She repeated that her defence, Mr Callis, had stated in the previous hearing that she was doing what three successive Home Secretaries had declared to be perfectly legal. It was however to no avail and though two counts were dismissed she was fined £25 and costs and was sent to prison for the contempt along with fellow accused Professor Vane and Madame Elvira. £25 (over £3k today) was half of Madame Elvira’s £50 rent for the season in her booth at the Tower where she had been for seven years. Elvira, like Ida and Albert Ellis, left the town and chose what was probably her native Cardiff to continue her profession until her own death in 1944.

Ida’s time in gaol was cut short as she was released in mid November, her fine being paid by the generosity of a Mr F Ash. The whole affair was in the hands of the Home Office on appeal where prominent public men called her imprisonment ‘a scandal and an outrage.’ Since she was no longer in prison it seems that Albert had discontinued the Appeal. At the same time, Professor Vane is also released from prison and he had no idea how, or who, had paid for his release. In her usual eloquent and articulate style, Ida thanked the anonymous donor through the columns of the newspapers. A Mr Ash who was unknown both to Ida and Albert at the time, turns up later, quite coincidently, as a local council candidate on the same Brunswick Ward as Albert.

And in the same year of 1904, in between Ida’s first court appearance and her sentencing in November Albert, finding an opportunity to swipe back at those in the Council who were responsible for bringing his wife to court, and as a member of the Municipal Reform Association, found the time to complain forcibly about the status of the alderman. These men, before they embarked upon their political careers, made promises to the electorate when they wanted to be elected to the Council but, when they had been elected and later co-opted as alderman, their positions safe, he could demonstrate that they were in the habit of changing their minds about certain policies that suited them. Albert Ellis in wanting the alderman to be voted in by the electorate rather than co-opted in by their friends on the Council, revealed this by reading letters written by the former prospective candidates and their unconverted political promises at present. He upset many Council members and strong language was used in a bitter row. Councillor Grime accused Councillor Ellis of buying his vote by spilling out £21 on drinks in the Farmer’s Arms in Chapel Street. Several members of the Council chose to leave the building and though the vote to abolish the post of alderman was taken, it was voided because there wasn’t enough Councillors left in the room to validate the vote.

In October of 1905 Councillor Ellis was once more at the throats of the perceived sinecures in the Council chamber where it seems that both the Liberals and the Conservatives were fed up of the muck stirring Councillor Ellis, and had joined forces to oust him from his post at the next election and in this respect Councillors Charnley and Ash were to collude in the Brunswick Ward. It is interesting, if ironic, to note the Fred Ash who had allegedly paid for the release of Ida Ellis would want to have a hand in getting rid of her husband from the Council. In the elections of November Albert Ellis was however, re-elected as Councillor.

At the end of October of the same year, it was little wonder that the Council wanted rid of Councillor Ellis as his criticism of their integrity and equivocation continued. It was concerning a free plot of land in between Revoe Library and the gymnasium which, owned by the Council, had been offered for sale but it was Councillor Ellis’s contention that the land had already been offered for sale to someone who was a relative of an alderman. A draft contract had allegedly been agreed with a Miss Barker and hence this could only amount to favouritism. Councillor Ellis maintained that the sale of public land should be made public and not be conducted behind closed doors. In the same Council meeting, Councillor Ellis backed a claim for compensation by the Bonny family whose stables had been damaged by the widening of the Promenade. It seems that the Pier Company had already received compensation, in which Councillor Bickerstaffe had a vested interest, for the same reason, and Councillor Ellis claimed that if the Pier Company could claim compensation, then anybody else had an equal right to do so.

In September of 1906, the land upon which the fairground was situated at South Shore was up for sale as valuable building land to be sold in three lots. It was part of the Star Estate Company and was a prime site for itinerant gypsies to encamp and a German troupe had settled there charging 2d for entry to the public. It was an affront to the Council who declared them dirty, dishevelled and lacking in any kind of sanitation and would have them removed. This was entirely opposite to the removal of Alma Boswell who had lived on the site as a tenant of the site for £12 a year for the 54 years of his life, his parents arriving he states in 1810. It was a condition of the Council that the gypsy tenants had to be removed if planning permission was to be given for development.

In this year of 1906, a somewhat militant and defiant Councillor Albert Ellis addressed a meeting of his Brunswick Ward constituents in the Station Coffee House (itself owned by Alderman Heap). His aim was to clear up the scandal that had surrounded him at the elections the previous November, and the reverberations of which persisted among his rivals and enemies in the Council. His victory in the election ‘was one against the aldermanic clique; against the Press, which the aldermen owned; and last but least it was a great victory against cant and hypocrisy’. This was reported in the Preston paper, rather than the Blackpool one. If it is believed that today’s politics are owned in self-interest by the press and the BBC is owned by the politicians who own the press then politics can never be democratic. Councillor Ellis’s words are as fresh today as they were at that time.

He had taken out a writ against Councillor Grime concerning the same the previous year and had not his wife Ida been released then he would have pursued his already enacted approach to the Home Office for an enquiry to expose the affairs of the Council. Had he done so, and if he were to ‘repeat all the scandal he had heard about the public men of Blackpool – aldermen and councillors, and even magistrates – the lawyers would be very busy indeed sending out writs.’ After all, Councillor Grime had agreed compensation for his libellous remarks and paid sufficiently to negate the maximum £25 fine and costs.

The campaign against him was led by Alderman Bickerstaffe and the local paper, owned by Alderman Grime didn’t report the event as solely to oust the candidacy of Councillor Ellis. It was left to the Preston paper to report the incident and justify its report against the objection of its neighbouring town. Albert Ellis was prepared to work with the other Councillors in a hypocrisy free atmosphere, though he could never befriend any of them. He also had severe words for the Christian ministers of the Blackpool churches maintaining that the misery of the human condition is exacerbated by the rigid contention that birth control is immoral. Ultimately, a religion, while a beneficial psychological and emotional easement for the individual and a secure collective, social cement is nevertheless founded on belief alone and the unmoving justification of that belief is a major cause of the scepticism, fear and suspicion of others and leads to many a desperate human conflict and tragedy. Councillor Ellis was prepared to live and let live, unlike his opponents. Let the Mormons and the Spiritualists on the beach. The diocesan bishop of Blackburn and his followers (and at one time in 1909 chased the suffragists off the beach with violence) worshipped on the beach so why not others? The objection put by the Council in favour of banning these religious groups from the beach was that money dealing on the beach was not allowed. (If this was the case then it would explain why the church meetings were so popular if they didn’t include a collection plate during or at the end of each service.)

In May of 1907 Councillor Ellis’s appointment as vice chairman to the Building Plans Committee was called into question by his enemies most particularly Councillor Bickerstaffe who did not like the method of his appointment rather the appointment itself, he claimed, as did Councillor Grime. It was Councillor Ellis’s opponents in a quieter mood of criticism.

In November of 1907 Councillor Ellis was once more on the defensive though it was to go on the attack as the best means of defence intimating the less than ingenuous conduct of his arch enemies on the Council and vowing to never let them ‘hound him out of public life’. He was once more at the Station Coffee House addressing his constituents at length but first he gave praise and sympathy to Alderman Heap, the co-owner of the place, who had just undergone a successful operation and had recently been awarded the freedom of the Borough. He was keen to demonstrate that he had defeated the disingenuousness of his detractors. He was an ordinary man and didn’t like baubles and titles and was even slightly uncomfortable when he was referred to as ‘Councillor’ Ellis rather than the man he was just plain old Albert Ellis. He was grateful that he been elected as a member to the Fylde Board of Guardians and in his Liberal minded politics he would immediately begin inquiry into certain matters to the Local Government Board and, further than that to the Board of Trade to complain about breaches of law perpetrated by the central Pier Company in which his arch enemy John Bickerstaffe was on the board. He suggested too, that money should be put into sewerage improvement rather than overspent on advertising and that the Council’s decision not to buy the Raikes Hall Gardens did not tally with their expenditure elsewhere, monies which were somewhat wasted. (He was actually in favour of the Council buying the site for the proposed library and the Queen Street proposal at the time had been quashed). But he showed good business acumen and sincerity of purpose against what he considered, in his enemies, their cliquishness and their collective self-interest rather than the common good. He also was able to refute the allegations that he attempted to sell off a piece of land owned by the Corporation at a profit to himself and, when the vote of confidence in him was passed at the end of the meeting, he went on to say in conclusion, that, ‘The men whose names he would not soil his lips by naming had done their worst by sending his wife to prison. They could not do anything worse than that, but they would find it the hardest task ever attempted in Blackpool or the world to try and hound him out of public life.’

Also in 1907 the Council was critical of the fairground at South Shore and claimed it was destroying a once desirable area which had deteriorated drastically. If Albert owned this fairground, known as the Exhibition Grounds, then Frank was certainly the manager, advertising spaces available in 1909 and giving the telephone number for his No 82 Central Beach address as Blackpool 290 or telegram, ‘Spaces, Blackpool’.

In the following year of 1908 the Ellis family published, ‘How to Improve Body, Brain and Mind’ by Albert, Ida and Frank Ellis. It was published in Blackpool and cost 6d (5p), and Ida is still on the road and at the same County Hall trades exhibition in Salisbury as a respectable palmist where Frank is the manager of the event. Also in the same year Frank is selling off a quantity of uniforms which would potentially suit bandsmen or skating rink, a connection which my imagination won’t allow me to make at this present moment.

In March of 1908 discussions at the Council in a Board of Trade enquiry, concerned the widening of the Central Pier. The Pier Company claimed the widening was essential for safety and extra upright piles had already been put in place. Councillor Ellis was objecting on behalf of the ratepayers. It seemed that one of his less objections was that the safety issue could be resolved by removing dancing from the end of the pier which exaggerated the stress put on the pier structure with such a ‘large mass of moving humanity.’ (The piers were packed shoulder to shoulder on a busy day so this could be understood as reasonable observation.) His main objection however was that the widening of the pier had been carried out without the permission of the Board of Trade through an official order, and it was an insult to Blackpool and its ratepayers that the work should have been carried out without that permission. It was either Albert’s commitment to correctness and his Liberal politics or just an excuse to get at his adversaries in the Council chamber. It was a ploy of his to quote what has previously been claimed in writing by those against who he is objecting to and he reads out a statement, proudly put, in the local paper by Mr Rowlands the chairman of the Company that they were going to construct a ‘thundering big pavilion’, thus impuning the honesty of the pier company to build whatever it wanted, and to get around any rules in the process.

The Company also wanted to increase volume on the pier and extend the structure westwards as well as add an extra width referred to, and would give no undertaking to exclude the construction of buildings as shops or shelters as part of the development. When the proposal to erect shelters on the pier was discussed, the famed contribution of Blackpool’s piers towards the proliferation of humanity was referred to by one of Albert Ellis’s co-objectors, Mr McVittie with a tongue gently in his cheek, you would imagine, when he claimed, amidst laughter, that they had, ‘ ‘‘funny things’’ happening in Blackpool, and what might be a shelter one day might be a kind of menagerie tomorrow.’ Albert, once an occupant of one of the buildings on the pier as a phrenologist claimed that buildings erected with permission of the 1891 provisional order tended to be used differently to the provisions of the order, changed at the whim of the pier Company as time went on. The report was then concluded and transferred back to the Board of Trade for decision.

In 1909, there was a large round up of gypsies charged with fortune telling after a police sting. The undercover policemen had crossed the palms of the accused women, Regenda Townsend, Louisa Young, Adelaide Smith and a very young girl, Clara Boswell, with a silver sixpence (2½p) in their tents upon the sands at South Shore. They could make £10 a day it was claimed, as much as some of today’s Brechtian beggars in the town centre. Incredibly, using an online inflation calculator, £10 in 1909 is approximated about £1140 today. Eva Franklin a gypsy of 17 Clare Street and with a tent on the sands had been in the town for 40 years and the gypsies had always been an attraction to the holidaymakers there. There was no deception involved they innocently claimed. But the land at South Shore was earmarked for development so, deception or not, their time was up and they were soon expected to move into more permanent accommodation.

At the Magistrates Court the defence solicitor asked the policemen if they had noticed, or knew of, the Ellis’s who had a massive sign outside their premises on South Beach and, if so, why did not they arrest them, too. The constables denied any knowledge or even noticing the signage displayed in large letters on the building frontage. It was perhaps that the policemen had not been trained in observation or it was the Chief Constable’s policy to get at the gypsies via pressures from the Council (as Chief Constable Dereham appeared to be a fair minded chap, a manner which his son, also Chief Constable, would continue.) It was a time when the gypsies had to be cleared off the beach in order to develop the South Shore and create the Pleasure Beach out of the Fairground. Councillor Bean would lose his rent from the gypsy tenants at up to £20 a tent or hut, but would go on to create what has become, today, an iconic place of entertainment and amusement. Today the site would have been designated an SSSI, making development more difficult but times are different today, land is increasingly more scarce and precious.

The controversy over whether fortune telling was deceptive or not continued but the three adult women were fined 10s (50p) and the young Clara Boswell bound over under probation for three months. The Ellis’s were left alone in this case since they would not have given the prosecutors such an easy ride.

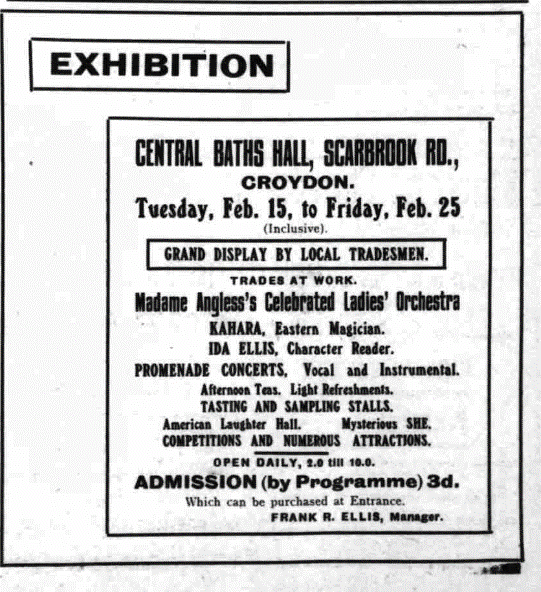

Though Albert did travel on occasion, he was largely, it seems, involved in his other activities at home and Ida continued to take the show on the road and she, with Frank as manager appeared at the Croydon trades show in February of 1910. If Albert didn’t travel too often with the other two it was possibly not only because of his business interests at home but because of the potential discomfort of his missing leg.

Albert left public life around the end of the decade and now the newspapers are quiet, the gypsies have been moved from their accommodation in South Shore into more permanent residencies and there is less controversy over fortune telling as it has now been tamed to a state of respectable curiosity, and Councillor Bean’s Pleasure Beach was up and running in its early stages. Ida continues to publish and tour while Albert continues to look to his business interests and they lead a quieter life. They have now moved to a more exclusive area of the town on Lytham Road with illustrious neighbours such as Pennington, Bean, Fish, and Watson and Grundy further along.

It is a relatively quiet period for the Ellis’s and they can relax more in the wealth of their success, away from the hustle and bustle of the busy Promenade. But in the war years Blackpool was as busy as ever as military recruits filled up the accommodation of the town to undertake their training. It was also the headquarters of the RAMC, the medical arm of the military and the trams would trundle past their house on Lytham Road to and from one of the largest military Convalescent hospitals in the country and the pitched tents of the soldiers next to it, which had taken up much of the golf course, at Squires Gate.

In 1911 Ida published her book ’Colours, Their Relation to the Physical, Mental and Spiritual Development of Man,’ and in 1912 she addressed a convention on Mental Science held in her adopted town of Blackpool, where she explained both the strengths and the limitations of reading the palms, and there is a little insight in just how she understood and practised her profession. Palmistry, she reveals, was no more exact than the sciences of healing or psychology. Frank Ellis continued to rent a furnished first floor bedroom for 10s (50p) at 82 Central Beach off his brother. It is Frank who continues overtly with the one to one palm reading sessions and is active into the 1930’s and until his death in late 1939. On the 1939 register the address for Frank Ellis is obscured but appears to be Blackpool Central. Frank is still single and describes himself as an ‘incorporated character reader’.

But in 1913, the controversy that was part and parcel of the life of anyone living on the edge of knowledge, reasoning or convention, took a different turn. In the couple of weeks before Christmas, Ida was summoned before the Sudbury Board of Guardians, and she made the gruelling three day round trip to Suffolk to present herself before them. It was for the payment of a maintenance order regarding her father who was now, at 78 years old, an inmate of the Sudbury Union Workhouse where he had been since Nov 1912. She had been summoned previously but had not appeared in person. During the proceedings she conducted herself with her usual, calm dignity and eloquence in the face of abrupt criticism and derision, even to the status of her name, which was understood to be Eliza, her professional name being Ida. But she was up to the task of confronting men who would demean her profession and patronise her female status. After all she was a self-made woman and could have considered herself far superior to her accusers. She claimed she had no means to support her father because she didn’t earn an income, it was rather that all the money that came from her employment went to her husband which was used in the household budget. Albert would have been aware of the economic advantage of that and that’s why he ultimately became rich and left over £70,000 in his will and Ida who followed six years after him with £30,000 from their mansion in Cornwall. A payment of 1s (5p) a week was already being paid by her husband but he had stopped this as soon as proceedings against his wife had begun. If the Ellis’s made money, they maintained a certain level of generous principle, too, in the Liberalism of Albert’s politics and the genuine seriousness of Ida’s convictions.

Her father, Mr Charles Mitchell had two sons, working in London, and seven daughters and each contributed 1s a week. His daughter Eliza was found to be living and working in Blackpool and married to Mr Ellis who was an ‘auctioneer, estate agent, company secretary, insurance agent etc.’, so it reasonable to understand that there was money available to pay. Mr Ellis’s assets were described as rented premises on Central Promenade assessed at £30 per year. They had a shop and a house which were their own property and the private house was assessed with a rateable value of £40. Albert seems to have owned and let out several properties and had offices to let at the address at 84 Central Beach.

To investigate the case, an officer from the Sudbury Board had visited Blackpool, staked out the premises, and had his hand read by Ida (or Eliza as they preferred to call her). He had expected to find her married to a labourer and so would have been quite surprised to find a woman involved in a wealthy business and successful business enterprise. (It was actually Uncle Albert Ellis who was working as a labourer – he was a sand shifter for the Council.) Mr Scrace the relieving officer, revealed who he was, unlike the policemen previously, when he was asked if he was willing to pay the contributory 1s. She said she did not earn anything and she would have to consult her husband which she did by using the telephone. In the arranged interview with the officer later, Albert claimed that he was not in a position to contribute as he was already paying the balance of 7s of the 9s payable for his own father, the other 2s (1s each) being paid by his two brothers. He had nevertheless agreed to pay the 1s for his wife’s father but defaulted when a summons was taken out against her. The Bench had unanimously given an order for 5s (25p) weekly and costs of 2s 6d (12.5p).

Ida took the stand and conducted her own defence under oath but despite the confident and quiet articulation of her statements, she was ordered to pay £2 13s 6d (£2.67½p) in arrears and the Board refused to rescind the order against her.

Things perhaps go quiet again for the family after that as they are able to remain out of the limelight and in 1917 Ida advertised her re-edited and improved edition of her catechism in the Tatler (published again in 1920) and other papers, and in 1918 she publishes a reprint of the 1911, ‘Colours: The Law of Colour in Relation to Character, Capacity and Health, Physical, Mental and Spiritual.’ This later edition included a section on astrology. There are many copies of the Ellis’s publications available today.

The 1920’s is an even quieter public period for the Ellis’s. Albert Ernest, Ida and Frank William Ernest Ellis are resident at 384 Lytham Road in between Arnold House and Rawcliffe’s Yard, and by 1923 the Penningtons have now moved in next door. In 1924 Annie Isabel Ellis is now at the address. Annie is a cousin of Albert’s whose Uncle Albert had moved to Blackpool and lived on Louise Street. Annie has some kind of infirmity, her mother is dead prior to 1911 and it may be that Albert has since died or unable to look after her. From 1926 the address on Lytham Road has changed to No 504, perhaps a number change subject to continuing building and growth in the road and living at the address (where Ida is referred to Ida Eliza) are Albert and Ida, Albert’s brother Frank and cousin Annie Isabel Ellis. They maintain this address until their move to Cornwall though also have an address in London.

On 21st November 1925 Albert and Ida take a trip to Madras, India on board the Malda and Albert’s occupation is given as a farmer. Maybe it had always been a dream of his to be a farmer, and was indeed realised when he moved to live amidst the farmland of Cornwall.

The journey to Madras (now Chennai) in India can be understood because it is in 1907 that Annie Besant became president of the Theosophical Society whose international headquarters were, by then, located in Adyar, Madras (Chennai). She had published a book on birth control along with Charles Bradlaugh and it is these two names that are mentioned in condemning the Ellis’s publications ‘Know Thyself’ (a reflection of Socratic philosophy in the name) as obscene by the Batley authorities. In Blackpool the Ellis’s played out their lesser part in this late Victorian surge towards the questioning of standard morality and argued their case. Albert references Malthusian principles in his argument against the church goer, the good Christian men of the Blackpool Council, in showing their equivocation and of course swipes at Councillor Bickerstaffe at the time for rallying the churchmen against the principle of birth control.

By 1930 only Albert and Ida are on the electoral register at the premises on Lytham Road though they are non-resident, having a business vote qualification. Their residence in this year is among the affluence of Bayswater and given as 45 Lancaster Gate Hyde Park, London on the electoral registers. Neighbours in Blackpool now are Frank Pennington at Arnold House and at No 486 are the Thompsons and Mrs Lilian Bean of the Pleasure Beach. More houses have been constructed up to Rawcliffe’s Yard.

While Frank continued to work in Blackpool, with an address at 86 Harrowside where he lived with his infirm cousin Annie Isabel, though continuing for some time to work from the office of the Promenade address, Albert and Ida had moved to Cornwall in 1930 and in 1933 Trewinnard Manor St Erth was for sale. Albert bought this shortly before he died.

They had moved to Cornwall having come from Blackpool as visitors and both he and Ida must have fallen for the district. They first took up residence at No 1 St Mary’s Terrace, Penzance and when they retired to this much more peaceful spot, they put their former lives behind them and lived the rural life that they had been used to as children. There was not an ology or an onomy or other etymologically compound Greek word in sight except for the eulogy of Albert’s eventual obituary. A rich and generously minded man, he favoured the town and district with his magnanimity and was well liked. He became a County Councillor and secretary of the Rotary Club, and he even offered part of his estate for a municipal airport. A lasting gift for the town was the mayoral chain of office presented in 1933. He and Ida seemed to have adopted a new phase of their life, away from controversy and for Ida it would be back to her rural roots.

Less controversial but busy and involved in the affairs of the County and Penzance in particular, he was largely liked and popular but had the reputation among some as being confidently opinionated, knowledgeable and tough to contest in an argument and few had tried it. At the inaugural meeting of the Penzance Model yacht Club in October of 1932 Councillor Ellis was still considered an outsider but had held his own and lasted longer in politics than expected and had already contributed many things to the town. One of the purposes of the meeting was to decide on a site on a suitable pool for the model boats and Councillor Ellis was able to dip into his experience of the Fylde Coast and he described the pool at Fleetwood, ‘if not the best but certainly the largest model yacht racing pool in England’. He was also very near the top of the subscription list (behind Lord St Leven, the influential Bolitho’s and Walter Runciman Liberal MP for St Ives) for the Royal Mount Bay Regatta, the large bay that stretches out beyond Penzance.

But he never entirely severed his ties with Blackpool and returned each year to visit friends and family and to view the properties that he continued to own in the town and he was still a rate payer. In May of 1933 he wrote to the ‘Blackpool Times and Fleetwood Express’ in advance of him spending a month in the town from mid June. He had left Blackpool to find an ‘equable climate’ and ‘after travelling in India, Ceylon, Africa and Europe’ for just that, he found it in Penzance and it was ‘without the pests which accompany eternal sunshine’. But for all its fertile hills, valleys and beautiful semi tropical gardens and an equable climate all free of charge, there is nothing happening on a Sunday when only churches and chapels are open and you have to drive out of town to get any of the excitement that Blackpool can offer in abundance seven days a week.

In June of 1933 he wrote back to the Cornishman newspaper from Blackpool concerning his visit. A man whose money was distributed with generosity was however, made by being cannily careful and he was thus shamelessly encouraged to make the visit to Blackpool during the promotional Guest Week when visitors staying more than four days received free tram ride passes, entrance to all the piers, the Winter Gardens, Tower, free tennis, bowls and putting, free entrance to the ‘finest open air swimming pool in the world’ and a concession in the cost of the hotel bills.

The journey was broken at Kidderminster and resumed the next day. He had noticed the proliferation of advertising boards which he felt spoilt the looks of the countryside of his adopted county and he felt his complaints in the Council chamber about just that were justified as he had travelled through. The rural beauty of Shropshire and Cheshire was in stark contrast to the industrial boiler room that was South Lancashire and there was every justification for Blackpool to provide such diversions as it did for those who lived and worked in such demoralising conditions. A keen sportsman, his first job after picking up more concessionary tickets from the Corporation offices, was to attend the last leg of the Manchester to Lytham walk, whose competitors had completed the distance in less than 8¼ hours, and suggested that a similar event (Bodmin to Penzance) should be held in the West Country. He did meet up with old friends and attended a divine service one morning, divine I guess meaning conventionally religious rather than out of this world, and he shook hands with so many former friends that his hand was nearly taken from his arm. He must have been well liked by the majority of folk but everyone has to have at least one enemy despite a façade of popularity. His only concern was that he couldn’t find his car after the service and was slightly worried that it had gone the way of the 3,000 cars that had been stolen in the borough in the last year. But he need not have worried because when his chauffeur came running up to him he explained that the vicar, learning that the car with the chauffeur in it belonged to Albert Ellis, and knowing of the generous nature of the former Blackpool Councillor, had asked the driver if he was able to collect his cap from the vestry of his church where he had left it. The chauffeur, too must have been confident of the nature of his employer, went to get the get the cap – and got back just in time.

During his stay, which wasn’t all holiday, he attended lectures given by the Royal Sanitary Institute, whose Congress was being held in Blackpool at the Winter Gardens where the Spanish Hall is a ‘sight for angels’ and the Opera House is a ‘wonderful place, worthy of a greater city’, in that week in June and hoped that some of the knowledge gained there would be useful on his return to the Council chambers at Penzance.

Albert died at Trewinnard on 3rd October 1934 after being ill for some time but always reluctant to relinquish his municipal duties for the sake of his illness. He was cremated in Bristol and it seems that his ashes were brought back to the family home and buried there. He left effects of £71,855 (close to £50m) today to his wife Ida Eliza Ellis.

His obituary is one long eulogy and his memorial service at St Mary’s Church Penzance was attended by virtually every official in public affairs, religion, sport and education and many more in the district.

‘He only came to our town in 1930, and yet in a short period of four years he became one of the best known men in Penzance and neighbourhood. He has left his mark on the town of his adoption in a way which it is not allowed for many of us to do.’

‘He was a man of great courage, and there are not many men who overcame a physical disability as he did.’

‘There was no cause in the town that appealed for his support which did not find him a ready and generous donor, and he gave irrespective of creed.’

His experience on the town Council in Blackpool had given him a head start for the municipal work in his adopted district and becoming a valuable member on the Penzance Council. He bought up the estate at Penalverne which had been an obstacle to the development of ‘workmen’s cottages’ thus facilitating their construction. Much town improvement in Penzance is due to his foresight and generosity.

Albert was cremated at Arnos Vale cemetery Bristol on the 8th October 1934 and attended by Ida and his brother Frank.

After Albert’s death, the family continued to live at Trewinnard. Ida is living with her married son and family there. Frank is a practising solicitor in British Honduras (now Belize in Central America). There are couple of incidents connected with them until Ida herself died in 1940. At the time of her death, the confusion in the minds of the human being that their efforts had been focussed on resolving in their own ways had begun to express itself in yet another World War. ‘Know Thyself’ was advice that was both misunderstood or ignored as prejudicial idealism had become a common cause and could only be resolved by the desperation and pain of conflict.

In 1937 a car driven by Miss Ellis of Trewinnard manor was in collision with a car driven by Bishop Sara of Truro Cathedral. Her car was damaged. His car was wrecked. Neither received serious injuries but Bishop Sara had to cancel his attendance at Truro Cathedral for a service. In this year too, a Mrs T Ellis organised and financed a tea party for the children of the Council school, so keeping up with the good work of Albert.

Ida Ellis died 7th February 1940 at Trewinnard manor and left effects of £36,901 (over £25m today) to her colonial solicitor son, Frank Raphael Ernest Ellis.

Sources and Acknowledgements.