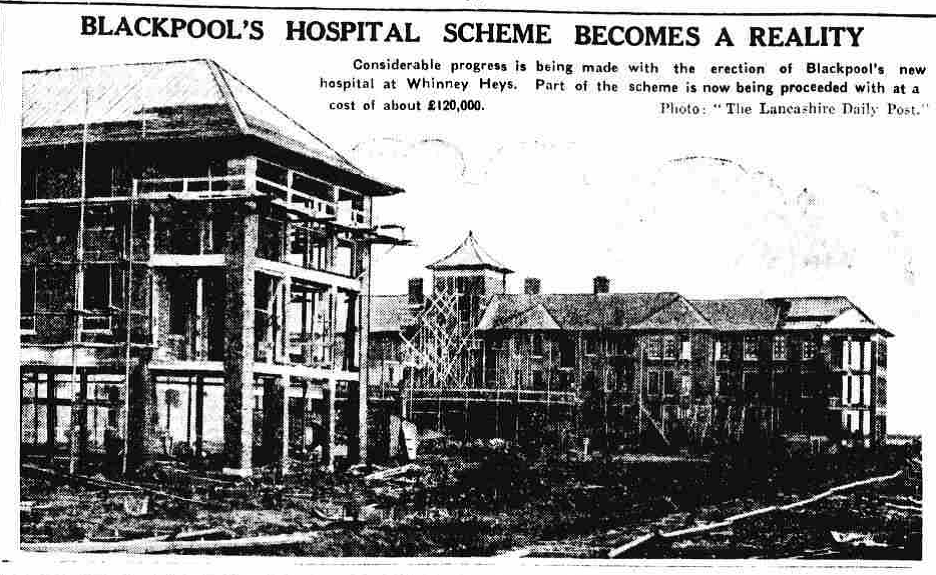

The Whinney Heys Story

Whinney Heys as the site of the existing Victoria Hospital, and the name of the perimeter road within which the Hospital is contained, belies the fact that it was once open land, resplendently yellow in the summer months when the settling Norsemen had first given a name to it. The extensive and vivid brightness of the yellow gorse on the small area of raised land in the middle of an area of generally, flat and sometimes marshy landscape would indeed have been quite a spectacle, deserved of independent description. The site is situated on a higher point, later referred to as the Whinney Heys Uplands, with views over the surrounding countryside in all directions, and was later an ideal place to construct a country manor house and to reap the benefit of the profitable agriculture that the land around it could provide.

The researchable story of Whinney Heys begins with the written records of the late mediaeval period, before which Celtic, Romano British, Anglo Saxon and Viking settled and left the evidence of their place names across the Fylde, and from the Norman Conquest it witnessed the evolution and decline of feudal society until relatively recent times.

It seems that, before the hall was built the estate was owned by William Fleetwood and the ‘gentleman’s residence’ of Whinney Heys Hall, was constructed in 1570 or 1575 when it was acquired by James Massey of Carleton, perceivably to complement the land he owned and create a residential estate. A couple of seen descriptions have different dates, but it suffices to say that the records put it around the last quarter of the 16th century. There is suggestion of conflict within the Fleetwood family in the selling off of land, especially perhaps to James Masssey who already owned land and was acquiring more in a perceivably rival kind of way.

So, it seems that at the beginning of the records, James Massey owned the Whinney Heys estate and the Masseys (sometimes written ‘Massie’) remained there until John Massey (Massie) died, reportedly in 1618 without a male heir and the estate passed through marriage, to the Veales, a local family with a residence at the nearby Mythop Hall.

The Veales also held property in Bispham, of which church, All Hallows, they were the patrons. The name also appears about the same time in Great Marton where Antonius Veale, a younger branch of the family name resided with his wife Ann.

The Veale name first appears in the parish records at Whinney Heys in 1597 through to the last seen entry of 1747. From1597 to the death of John Massey in 1618, Edward’s status at the Hall might be of tenant until ownership of the estate passed to him.

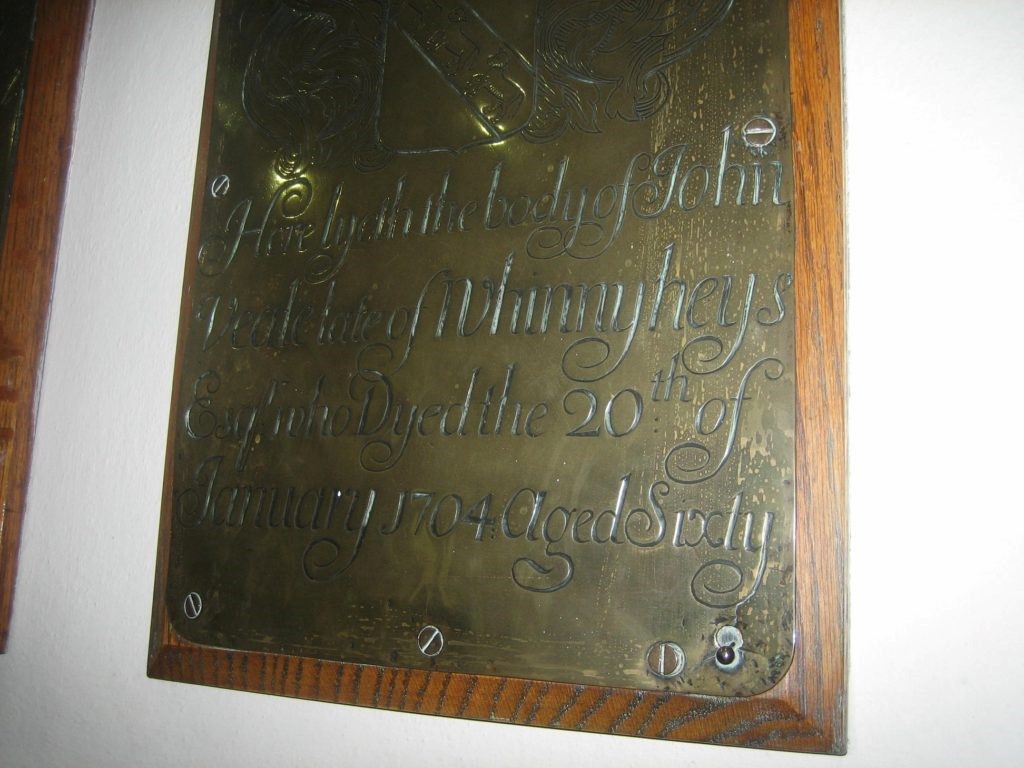

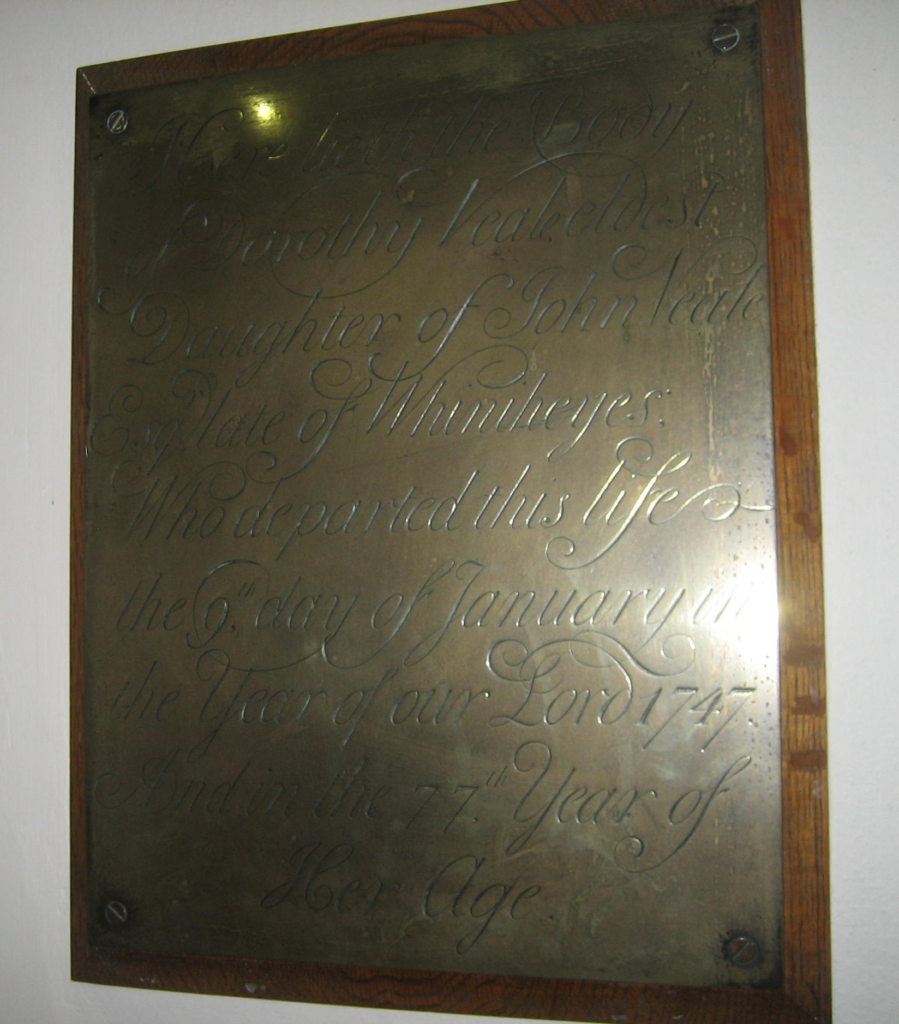

The Veale family plaques at Bispham Parish Church with the kind permission of the Church Wardens and the generous help of Denys Barber

From this date the large estates of the landed gentry, were gradually reduced and partitioned and the area becomes a farmland occupied with the relatively smaller farms of often quite wealthy yeoman farmers of high status as owners or tenants. From commentary on the Tyldesley diaries quoted in the Preston Chronicle of July 1872 we read, ‘Whinney Heys is situated on a hill in S E Layton but the present farm house is only an abridgement of the ancient hall, and scarcely a vestige remains of the plantations which formerly surrounded it.’ It is a description which reflected the changing farming landscape from large estates to smaller farms managed by influential yeoman famers and then later, to even smaller farms as industry and property development was taking over the ascendancy of farming for profitability. Further on into the 19th century the relative wealth of these farmers could be increased by land speculation on the coast, land for building which would be the continuing demise of farmland and agriculture, and would eventually consume the farms, creeping gradually inland to include Whinney Heys Farm itself.

In the mid to late 19th century, the farms would become the playthings of the property developers of the coast, successful businessmen who regarded farming and horse breeding, particularly at Whinney Heys, as a little bit of extra fun and status when complete reliability on the productivity of farming was not necessary. Whinney Heys was owned at the turn of the 19th/20th century, respectively by John Bickerstaffe and James Fish both with the title of Mayor of Blackpool and a large portfolio of properties on their CV’s. Much of this wealth was underwritten by the commercial success of Blackpool as a town, the urbanisation of which crept gradually yet inexorably inland to leave Whinney Heys today only as a name.

VEALE

It seems that there were four generations of the Veale family at Whinney Heys, Edward, John, John and Edward. The last Edward died without a son and, for the first time in the generations, the female, Edward’s sisters, acquired possession of the estate and, when they both married, it heralded the end of the Veale name as owners.

The Veal name first appears in the area in a military muster of 1574 when John Veale was obliged to furnish one caliver (arquebus) and one morian (rimmed helmet) and the Whinney Heys estate first comes into the possession of the Veale name as Edward the son of John Veale (living at Mythop at the time) married in the last decade of the 18th century (going by the first record of progeny, daughter Jane), in 1597. He had married Hellen (Ellen) Massie (Massey) who was a co-heiress of the Whinney Heys estate occupied by her father John Massie. Massie is a name which is not well represented in the Fylde but has an earlier pedigree and is mentioned as early as the 1500’s. Hellen’s sister Alice, the other co-heiress, married Thomas Bamber of Poulton (a ‘gentleman’ and also a longstanding Fylde landowner in the name). The estate thus passed into the hands of Edward Veale, eventually a magistrate for the county of Lancaster and referred to as Edward Veal de Whinney Heys, Armiger, (and so entitled to a coat of arms) and appears in the list of free tenants of 1621.

Edward’s address in 1597, 98 and 1600 (the latter two dates being the births of his children Ellin and Julian respectively, daughter and son), is stated as Poulton, and with the birth of Ann in May 1602, the abode is given specifically as Whinney Heys (Whyny Heies) for the first time, while an Anthony Veale and wife maintain the family name as resident at Mythop (Methop, Mithope).

Edward and Hellen have further children Alice 1603, Francis 1610, Dorothy (Doryty) 1611, Thomas 1613, Richard 1615 and James 1616.

After Edward, his son John Veal(e) is resident at Whinney Heys and is reportedly born in 1605 succeeding to his father’s estate, Edward having died in 1623. John married Dorothy Jepson of Yorkshire and their children, baptised at Bispham All Hallows, a church for which they were patrons, are Edward in May of 1632, (probably buried 1650) Ellen in September of 1633, Mathew in April of 1635 (buried April 1636), and Dorotie in November of 1639 (buried November 1639). His mother Ellin, dies in March 1634/5. It appears he was succeeded by his son John also, reportedly born in 1635 and who died in 1708. He had married Susannah Rishton who probably died in 1718 at Whinney Heys. After John’s death, his son, a clergyman, possibly the Edward Veale Esq of Whinney Heys, dies in 1723, without having married, and this left John’s daughters Sarah and Susannah as co-heiresses.

Sarah married Edward Fleetwood Esquire of Rossall Hall on 30 March 1713/14. They have a daughter Margaret (a ‘gentlewoman’) born in 1715 and who married Roger Hesketh Esquire of North Meols in 1733. Their son born 1738 succeeded to the title of Rossall Hall and who was the grandfather of Sir Peter Hesketh. Rossall Hall was converted into a school in 1844 and in 1872 known as Rossall College.

Susannah married John Fayle (previous occupant of Mains Hall before the Heskeths), of Thornton in 1704, and in 1718 Susannah Veal of Whinney Heys dies. John Fayle constructed the ‘Bridge House in Bispham’ in the ‘likeness of Whinney Heys’, (which is possibly Bridge End in Carleton, the residence at the birth of a son, John, to William Fayle in 1724). Dorothy Veale is the last of the name to be represented at Whinney Heys as her death is recorded in 1747/8 as being in Poulton but ‘formerly of Whinney Heys’.

From an extensive knowledge of both the district of Marton and the family history research of Philip Walsh, there is a Thomas Hill who is resident at Whinney Heys in 1712, and there is a Thomas Hill born in Bispham in 1690 and thus he would only have been 22 years old at the time. The date is the baptism of the ‘base’ child of the seemingly unmarried couple, Thomas Hill and Elisabeth Singleton. Thomas was not afraid to own up to being the father of his and Elisabeth Singleton’s child. Whether any subsequent marriage was an obligation (which might then be described as an arquebus wedding) or a natural union of love is not known but they had more children together and from that natural union the family have been traced to a living family today. Documents also reveal the settling of disputes between the same Thomas Hill and other names associated with the neighbourhood (Butcher and Miller) in August of 1731 showing that Thomas Hill was perhaps running the farm, potentially as bailiff at that time.

With Sarah Veale’s marriage to Edward Fleetwood, the Hall passed back into the ownership of the Fleetwood name and, having a residence at Rossall Hall, it seems they had no need of a residence at Whinney Heys so, as valuable capital, it could eventually be sold off. The records aren’t clear as to who is resident at the Hall from this date up to 1771, when the Gretrix name moves into Whinney Heys, having bought it off the Fleetwood Heskeths. Nick Moore, in his exhaustive and meticulous chronological history of Blackpool, has the estate brought off the trustees of the Hesketh Fleetwoods in 1771 and New Whinney Heys built after the Gretrix’s moved in to the estate. There are now two Whinney Heys farms, the Old and the New.

The Veale name had seen Whinney Heys through some turbulent times in English history, after the written story is picked up some years later beyond the Reformation of 1532. The Fylde contained its Catholics, both recusant and compliant and reportedly off the Rossall coast, experienced the perhaps unwelcome visit of a wayward and desperate Spanish galleon of the Armada, an invasion attempt itself supported by Cardinal Allen snugly out of the way in Rome and in no need of the priest hidey hole in Mains Hall.

The inner, religious strife exacerbated by the Gunpowder Plot in largely Catholic Lancashire in the early years of the 17th century would have affected the gentry of the Fylde especially those who clandestinely adhered to the Catholic faith as Robert Cecil’s government spies in their search for the plotters combed the country. While deeper sympathies might have been innately hopeful of a return to a Catholic State, equally those sentiments would not have considered such violent and murderous means in achieving it.

The next two generations of Veale, would have experienced and lived through the Civil War, the battles of Preston and Wigan occurring uncomfortably close and where John Veale’s contemporary and neighbour, Thomas Tyldesley, as Commander of the Royalist forces met his death at Wigan and is commemorated there.

But in peace time it was a story of gentlemen and their ownership of large estates worked by a servile population. This ‘gentry’ would have been well acquainted with each other as neighbours and no doubt lived a life reflecting that of a Jane Austin or Bronte novel, as the daily diaries of Thomas Tyldesley of Foxhall later published in the Preston Herald as several weekly instalments relating to the years, 1712/13/14, record.

From his country residence of Fox Hall Thomas Tyldesley would visit his neighbours in Thornton, Poulton, Staining, Mains Hall Singleton, Rossall and Whinney Heys and it is a report of gentlemen riding to each other’s estates on horseback or coach, for idle chatter, business concerns and usually with a servant or two in attendance when the women, highly intelligent and astute and critical in their observations, would be confined to the drawing rooms engaged in repetitive activities considered as useful in keeping their imaginations away from idle thoughts. William Thornber gives to Mrs Veale, a rather Puritan nature of hard work and a distaste for the idle pastimes of those of her neighbours who would rather drink and gamble and probably do rude things, but which are not mentioned as such and for which the women would get the blame anyway. While Mrs Veale’s altruism or asceticism may be true, it is nevertheless William Thornber accrediting those qualities to her a hundred years later in the romanticism of his histories.

War and civil strife were also experienced during and at the end of the Veale’s occupancy of Whinney Heys as the Jacobite uprisings of 1715 and 1745 would see the military pass close to the Hall, and sometimes too close for comfort. The Fylde is on the direct route to and from the west of Scotland. Today you would take the M6 and get there within two hours at a casual speed. Before that it would be the A6, before that the turnpike and before that the Roman road, the vestiges of which can still be seen at the foot of the hills as you travel trough the Lake District on the modern road. The Scottish army, picking up English sympathisers on the way, would not consider paying turnpike fees nor collecting food and booty that was available en route with the need to ask or pay for it. While there might have been some sense of order in the army marching south, the unruly, bedraggled and retreating force that passed once more a little time later through the Fylde was just a marauding horde of desperate men, broken up into little groups. They were exhausted, hungry, cold and without suitable clothing for the prevailing weather conditions. While there were sympathisers to the Catholic cause in the Fylde, it didn’t matter to these desperate men, both friend and foe had what they desperately needed; food and clothing. For a short period, the Fylde was a lawless place. Though some of these marauders penetrated as far as Layton and it is quoted that valuables were spirited away by some of the local residents and hidden ‘as far away as Marton’, there is no evidence that Whinney Heys was attacked. However, both the Veales and the Gratrix’s in residence there, would have been extremely concerned for their own safeties as these men, with unkempt long hair and flowing beards by now, and the clothes hanging off them, looking more like lawless vagrants than soldiers, robbed with careless violence, taking away cattle and valuables from anywhere they could find. At Layton it is quoted that one of the marauders, desperate for a pair of shoes, of which many of them were in dire need as many were barefoot, dragged them off the feet of Thomas Miller with the words, ‘Hoot mon, but I mon take thy brogues.’ Whether this is a true quote nor not, it does demonstrate the violence that the Fylde was subjected to during this period. The attackers didn’t always have it all their own way though. A vigilante group of about forty men was gathered together by a farmer named Singleton who had been attacked by them. Armed with scythes and sickles and anything they could get hold off as a weapon, they tracked down the marauders, meeting up with them at a place which would get the name ‘Bloody Lane Ends’ near Wesham, after the skirmish and three of the culprits who were killed. Some local sympathising families, named as Sanderson, Cartmel and Wadsworth were executed at the time and buried at Garstang, while the local Garstang attorney, Robert Muncaster was hung at Preston. Such is the violence surrounding religious belief mixed with politics for those who are unable to compromise.

GRETRIX (Greatorix, Gratrix, Greatrix)

When the ownership of the estate passes to the Fleetwoods through the marriage of Sarah due the lack of a male, Veale heir, to take over Whinney Heys, the next occupants on the records towards the last quarter of the 18th century are the Gretrix’s, a name that has several variations of spelling. The Gretrixs are a Marton family.

The last date that the Veale name is recorded as referring to Whinney Heys is 1747/8 (when Dorothy Veale, ‘formerly of Whinney Heys’ dies) and the first date of the following tenants the Gratrix’s is 1754. The Greatrix’s were from Marton and had lately been resident at Mythop as farmers, as the Veales had been before them and it must have seemed like a natural progression to move to Whinney Heys which was not that far away. It seems that the Gretrix name took up the tenancy of the Hall when it became vacant and, after the death of the last remaining Veale in the middle of the 18th century, and bought the estate in 1771 when it came onto the market.

We now get both Old Whinney Heys Hall/Farm (the Old house is referred to as Whinney Heys Hall on the 1891 OS map) and is situated in what is now the Hospital complex. And now there is also New Whinney Heys, built at the time the Gretrix’s took over according to Nick Moore, and which is still on the 1942 OS map and is about where the zoo car park and the zoo entrance buildings are today. From this point the land plunges away northwards and then rises sharply to what is now the hospital site and its upland status.

From now on there is the confusion of there being two Whinney Heys, both the Old and the New and sometimes a reference to Whinney Heys could mean either, though each is situated in a different parish, the Old in Layton-with-Warbreck and the New in Hardhorn-with-Newton. The farms are neighbours with contiguous borders with the parish boundaries separating them. New Whinney Heys appears in its own right in the records that I’ve seen, at the beginning of the 19th century and in 1819 when historian William Thornber gets romantic again in recounting the murder of John Gratrix, the 49 year old farmer would have been on his way back to the Old Whinney Heys, the New Whinney Heys being occupied by his brother Richard in 1818. But there is always some confusion in the records as to which brother occupied which Whinney Heys. Both farms are included on the first OS map surveyed in the 1840’s, where the more southerly of the Whinneys is given the title of ‘New’.

The earliest date found for the Gretrix name at Whinney Heys is the recorded burial at St Chad’s Poulton of Thomas Greterix son of George Greterix on the 18th October 1754. A little later is the birth of George Gretorix, son of Richard and Susannah 5 May 1768 at All Hallows Church Bispham while residing at Whinney Heys, Layton. Richard it seems had married Susan Parkinson at St Michael’s on Wyre in 1767.

When the death of Richard Gretrix, yeoman is recorded in 1807, his address is given as New Whinney Heys, Hardhorn-with-Newton in the Fylde. ‘He weighed upwards of 27 stone.’ He was aged 64 and buried at St Chad’s Poulton. Four years later in 1811, Susannah, widow of Richard Greatrix, Whinney Heys is buried at St Chad’s Poulton. In June of the same year, William Gretrix married Dorothy Crookall at Poulton St Chad’ and they live at Whinney Heys in the parish of Poulton. The farm is inherited by his son John who marries Jane Dixon.

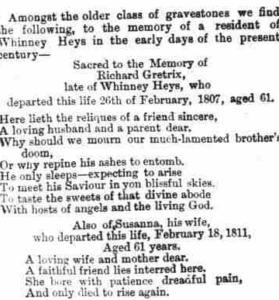

From the Blackpool Herald of July 3rd 1883, we read; ‘Amongst the older class of gravestones we find the following, to the memory of a resident of Whinney Heys in the early days of the present century –

On the 21st January 1770, the baptism of John Gretrix is recorded at Bispham Parish Church. His parents are Richard and Susannah. Their daughter Dolly is then born in May 1772. On 2nd of August of 1797 the marriage of Richard’s son, John Gretrix, husbandman, to Jane Dixon is recorded at All Hallows Church, Bispham and on the 9th March of the following year, their son Richard is born at Whinney Heys. (He dies aged 23 in 1821). It seems that John and Jane had married once Jane’s pregnancy had become evident.

Children born at Whinney Heys and baptised at All Hallows Bispham are; Richard in March 1798, Margaret in May 1799, Susannah on the 22 April 1801, Elisabeth in Feb 1803, George in Feb 1805, and Nanny in Jan 1807. A daughter Betty died 18 months old in 1804 and is buried at St Chad’s.

William occupies New Whinney Heys from 1813 as, in 1813, William and Dorothy Greatrix have a son Richard, baptised at Bispham and their abode is Whinney Heys. The 1818 auction announcement of the Whinney Heys estate is more definitive, placing John at Old and William at the New (the New being the larger of the two). It is described as good arable land and especially productive for wheat and green-cropping.

In 1819 the burial of 49 year old John Gretrix of Whinney Heys is recorded at Poulton. Whether he was murdered or not is speculation. We have only William Thornber’s word for this I believe. I haven’t come across an account in the newspapers of the day, when you would expect it to have been reported. Possibly with the demise of John Gretrix, murdered or not, the tenancy came to a natural conclusion (if his death hadn’t). By 1828 William and his wife Dorothy have a son Richard born in 1828 and their address is given as Dover. Dover Farm is a little south east of Staining and near the Mythop Toll gate on the road to Mythop across land drained and reclaimed by the Jollys some years before, so this would conclude the Gretrix tenancies of the estate and after which the farms were tenanted by the Wards and the Bambers respectively.

In 1847 the curious birth of a cow was recorded by Peter Hutchinson the vet from Poulton le Fylde. The cow belonged to Dorothy Gretrix of Dover farm Hardhorn-with-Newton and was born from a cow which was two months overdue. It had four ears, two large and two small, two of which were in the place where the eyes should have been and its head in general had the appearance of a pointer dog. It had a single eye in the middle of its head and was hairless apart from its chin and hooves.

In 1887 the obituary of John Gratrix gives a little information on the Gratrix name of the estate. He was born at Whinney Heys (‘near Blackpool’) in 1809 and died in Preston on the 23rd December. Like one of his brothers, he hadn’t stayed in farming but instead was an iron-founder and was the last surviving Member of the ‘Seven Men of Preston’. He had joined in partnership with his brother who had a spindle and fly works in Bridge Street in the town and succeeded his brother in the business. A quiet and retiring man, he was a Nonconformist, and a Liberal in ideas. The ‘Seven Men’ originated from a Sunday school meeting when that number of men present pledged abstinence from alcohol. John Gratrix was a staunch member of the Temperance movement. The movement eventually grew and became the Preston Temperance Society.

The Gretrix name would have lived through the effects of the French revolution and the rise of Napoleon when Britain, usually referred to only as England, in a nervous state took steps to defend itself from a French invasion. The pride in the victory at Waterloo lasted long enough in the popular mindset to give its name to roads and pubs in many towns and cities that had begun to expand along with the emerging industrial unrest of the Luddite riots and the dissatisfaction of Wellington as a politician. But Whinney Heys along with the Fylde Coast was far away from Europe and the town of Blackpool which eventually absorbed it was still advertised as such in that much worse of conflicts from 1914 to 1918, a place that was ‘far away from the Zeppelins.’

They had also lived through the time when sea bathing was seen as highly therapeutic and had become very popular for those who had the time and the money to spend some time there. The future of this popularity would ultimately be the demise of Whinney Heys, but it would first experience a heyday of popularity in the profitability of farming and horse breeding during the 19th century before it would be laid to rest and become the name of a road only.

BAMBER AND WARD

Agriculture now is a highly profitable business as it begins to feed the growing cities of the Industrial Revolution and there is now a different generation of smaller type farmers and farm owners competing against each other in the market place in root crops, (where the mangold wurtzel, now virtually extinct, enjoyed a popular status), grazing for cattle to produce milk and meat, and the breeding of that most versatile and respected of animals, the horse. Horses were a man’s best friend and pride and consideration were taken in their care and maintenance.

This was perhaps the golden age of agriculture before the industrial age took over. It was a life style which intimately involved the farmers, who were held with esteem in their neighbourhoods and the agricultural labourers who toiled the soil.

Since the tenancy agreements, unless otherwise stated, were on a fixed term of years, it provided a reason for the farm tenants to change regularly and it is tempting to think that there was a scramble to get onto one of the more profitable farms when it became vacant with a little jealous rivalry between the applicants.

Labourers would work from farm to farm and even follow their employer as they moved farms when the lease ran out. Recorded in the Manchester Courier of 1860, the story of John Simpson, farm labourer, recalled a life looking back from his octogenarian staus. Born in Carleton in 1780, he worked at many Fylde farms, including as teamsman to Richard Gratrix at Whinney Heys in Stalmine (his reported words, possibly means Staining) where he worked for seven years before moving to the farm of Richard’s son, John at Layton where he spent seven years. (Probably moving from the Old to the New Whinney Heys or vice versa.) He was back again at Richard Gratrix in 1800 and learning the ploughing skills by ‘following the horses’ at Newton to where the family had moved and continued his life as a farm labourer until he married in 1891 and went on to keep the Ship Inn at Poulton. The marriage lasted only until 1826 when his wife died at the age of 41 after which he sold up, worked for two years in service to Edward Jolly and went to work in Blackpool for eleven years before moving to Dicksons Hotel until 1850. While at the Ship Inn in Poulton and Dicksons hotel in Blackpool, he also worked as a teamsman on the farms. He remembered all the names of all the horses he worked with on all the different farms, thus showing a close association with the animals in the farming life. He gave up farming and for three bathing seasons he worked for Mr Dickson’s (at Dickson’s Hotel now the Metropole) and left there in 1850.

He was proud to be wearing the same clothes, his trousers (breeches) being made in 1819, his shirt in 1820, coat in 1823 and his waistcoat in 1825. He was also proud to claim that he wore these clothes to his wife’s funeral in 1826, his 82 year old brother’s in 1859, and brother-in-law of the same age in 1860, and his sister-in-law in the same year aged 88. He goes to church every Sunday…..in the same clothes. It seems he had his photograph taken in 1860. Whether this has survived or not is not known here.

Bamber 1829-1850

Bamber is a long standing and frequent name on the Fylde since the origin of the records in the 16th century. The Bambers had been in the tenancy of Whinney Heys since at least 1829 with the birth of their daughter Elizabeth recorded there, and are tenants when the estate is up for auction once more in 1832. Here the estate is recorded as comprising of two separate farms, the ‘Old’ and the ‘New’. 317 acres of ring fenced arable, meadow and pasture land and respectively in the occupations of Thomas Bamber and Richard Ward. Bamber was an ancient name, a Richard Bamber held land in Great Marton in 1607. Perhaps he had had his eyes on Whinney Heys for some time. The records show that Thomas Bamber occupied Old Whinney Heys and Richard Ward occupied New Whinney Heys. The Bambers held the tenancy up to the early 1850’s when Richard Rogers took over. The Wards held their tenancy until the early 1860s when James Lewtas took over.

The first mention of the Bambers in the newspapers at Whinney Heys is in March of 1834 with the sad and untimely death of 16 year old William Bamber, son of Thomas Bamber of Whinney Heys. The newspaper obituary describes him as ‘an amiable youth, and he is sincerely regretted by his friends and acquaintances’. Somewhat confusingly the newspaper reported in June of 1836 the death of 92 year old Margaret Bamber of Old Whinney Heys in the obits but there is no record of her death in the parish records and, rather strangely, also in 1836 the death of 92 year old Mrs Margaret Cookson at Old Whinney Heys and her demise is in the parish records. She is the widow of John Cookson of Midgeland, Marton, the former residence of Thomas Bamber and family. So probably a slip of a printing block or two by one of the compositors.

The Bambers are still at the farm in the April of 1839. In this year at St John’s Church, Alice the youngest daughter of Mr T Bamber of Whinney Heys married Mr Murdock Balfour, chief mate of the ‘Alice Brooks’ of Liverpool. Murdock Balfour would have been quite at home at Whinney Heys, a farm with neighbours as distant from another as his own neighbours were in Westray, Orkney. In March of 1839 the ship had arrived from Valparaiso with a cargo of wool, leather and copper ore and was due to leave for Adelaide and Port Philip on the 15th April but they were married by William Thornber on the 16th April of the same year, so there must have been a delay in loading the cargo which wouldn’t have pleased the captain but would have given the happy couple the time to get married. The vessel didn’t leave Liverpool until 22nd May. The vessel was back in Valparaiso in September so had made up the time. The Alice Brooks was a 212 ton barque, a Liverpool built vessel and carried goods and passengers to all over the world including South America, China, Africa and migrants to Australia in the period when shipping ruled before railways and flight. It was ‘a coppered vessel and well known as a remarkably fast sailer, and in every respect a first rate conveyance for both goods and passengers’ (though it was limited in space for passengers).

On the 1841 census, Thomas Bamber is not mentioned and Margaret is head of household at Whinney Heys. Hugh is there, as well as married sister, Alice (Balfour) and one year old son James (born in Blackpool in 1840). Alice had stayed at home and not accompanied her husband on the long and arduous return journey to Australia and back (in May 1840 the Alice Brooks was in Adelaide). By 1842 Alice was living at 30 John’s St Liverpool when son Thomas was born (this Thomas it seems married in Liverpool and can be traced through family trees to date). Alice also had a son David born in Liverpool in 1844. In 1851 Alice is on her own again with her seven year old son David, at 93 Sheaf Street Poulton.

The records show that it would always have been safer at home since, on October 27th 1857, along with her son and her husband, now master of the Ontario, she died at sea in a shipwreck off the Norfolk coast. The note on the record of the death states that her body was picked up off the beach at Caister. The Ontario was carrying coals from Newcastle. There was only a single survivor, the chief mate, who made it to the shore alive and was able to describe the wrecking. The somewhat mutilated bodies of the 20 or so crew were collected off the shore over the next couple of days and laid out in the lifeboat station at Caister. Alice’s face, mutilated and distorted after her drowning in the storm lashed seas, would not have recorded the pain and the fear of losing her husband, but more of being helpless to save her son before losing her own life in the pitch blackness of a storm-rent night. The tragedy is enhanced by the fact that the lifeboat was nowhere near fit enough to go out to sea, its water tanks in some disrepair among other faults. Had it been able to then it was considered that most of the crew would have been saved. Murdoch’s parents were James Balfour & Jean Rendall of Westray in the Orkney Islands. Born in 1813, he had gone to sea as apprentice in 1830 and eventually worked his way up to Master. The Bambers appeared to have had a Liverpool connection since both daughters’ marriages were to men living and working in Liverpool.

In the following year after Alice’s marriage, her sister Margaret of Whinney Heys married Osbertos Rowe, a book keeper of Harrington a man it seems of some means, involved in finance, from Liverpool and from a military background and whose father had fought in the Napoleonic Wars.

Later on in 1846 in a case of property ownership involving the Bambers of Whinney Heys it seems that John Bamber had got into debt and Thomas Bamber, his father of Whinney Heys, had tried to help him out by selling goods pledged to a Mr Jackson. John Bamber had a seasonal shop in Blackpool, as those in the farms could see the opportunity of dipping their toes into the lucrative market of Blackpool in the year that the railways arrived, bringing in day trippers by the thousand and ultimately sowing the seed of the town’s development and its eventual absorption of the surrounding farmland. It seems that, despite his brother Hugh going into the witness box and speaking for him, the case was made against them.

In December of 1850 Hugh Bamber, son of Thomas Bamber of Whinney Heys Farm, Layton, died at the age of 37. He had been married to Jane Long in November of the same year, and so only married less than a month. A son, Hugh Bamber was born in August of 1851. In 1851, 29 year old Thomas has scaled down his farming and is now on a 15 acre farm at the Fold, Marton. Margaret is still at home as well as son James and grandson James. Alice is not there but 11 year old James Balfour, who would be a grandson, is not mentioned.

After the Bambers, the Wards, Rogers and Lewtas’ time at Whinney Heys covered not only the Crimean war and its celebratory termination but also the mutual slaughter of the so-called Indian mutiny in the years following. Stories of the atrocities would have reached the eyes of those who could read and the ears of those who would listen to those who could read. They would be relieved no doubt to hear of the storming of Delhi but have the inability to share sympathy with other religious ideas or be concerned with any national sovereignty other than their own.

Those in occupation of Whinney Heys in 1856 would have witnessed the celebrations of the end of the war in the emerging town of Blackpool on the coast. They would have known or been aware of those that came from the war, Squire Clifton, the landowner or Lieutenant Ryecroft of South Shore. With the first introduction of gaslight in the streets and, unless involved in the extensive celebrations themselves, they possibly would have been able to see the lights in the distance from their advantage point of the Whinney Heys Uplands. Certainly they would have been able to hear the celebratory cannon fire. The celebrations coincided with the opening of the first promenade of the coastal town and they wouldn’t have known that in less than a hundred years’ time, the developing town on the coast would have covered all the land in front of it and would be washing over its threshold as much as the sea erodes the land or covers it.

WARD 1829 – c1856

The Ward family took over Whinney Heys about the same time as the Bambers. Whinney Heys is described as a single estate which included both Old and New Whinney Heys. Since the Wards are recorded at being in the parish of Hardhorn with Newton, it should be safe to conclude that they occupied New Whinney Heys.

Though the Wards are an ancient family of the Fylde, they first appear recorded at this address in April 1829 with the birth of a daughter, Elizabeth, to Robert and Margaret Ward of Whinney Heys and baptised at St Chad’s Poulton. In 1832 Richard Ward son of Robert and Peggy Ward was baptised at St Paul’s Marton and the abode is given as Marton.

In 1833 Whinney Heys keeps its Layton milling connection in the family when, Mr Richard Bonny of the Wheel Mill, Layton married Esther Ward, daughter of Mr Richard Ward, Whinney Heys, Staining. In March of 1835, William Ward of Whinney Heys married Elizabeth Jolly, daughter of James Jolly of Weeton and in July of 1836 Esther the daughter of Robert and Peggy Ward is baptised at St Chad’s Poulton and their abode is given as Marton. They had a choice at which church they baptised their children and the records reveal the inter marriage of the farming community.

In October of 1840 Margaret Ward, the eldest daughter of Richard Ward of Whinney Heys (Hardhorn) married joiner Thomas Topping of Blackpool at St John’s (vicar; Rev John Hull), and in the same year Richard’s 20 year old daughter Mary, marriedRoger Parkinson, later to take over Whinney Heys,so family ties once more were kept within Whinney Heys. Roger was lodging at the farm while working there in 1841. This 1841 census shows Richard is at Whinney Heys with his family, his wife Betty and his two daughters, Mary and Ellen. Both Mary and Ellen are given ages as 20 but the records show Mary born in Weeton in and Mary in Staining. Also lodging at the farm at the time among others were Mr and Mrs Topping, Thomas and Peggy. Peggy Topping is the now the married eldest daughter of the Wards.

The next farm on the census is Newton occupied by the Parkinsons and then Todderstaff farm after which is Staining occupied by Richard Gratrix so the farming community is shown to consist of familiar names, maintaining the continuity of ownership through a marriage qualification or moving from farm to farm opportunistically as tenancy agreements expire naturally or through the death of the tenant. Other farms in the immediate surroundings include Whitemoss, Wardloss and Puddle House.

The 1851 census shows 73 year old Richard at Whinney Heys a farm of 115 acres and employing two labourers. At home are wife Betty, Ann Thornton and Elisabeth Ward, described as nieces (grandchildren?) and four ‘nephews,’ and in February of the following year the last of Richard and Betty’s daughters, 32 year old Ellen Ward ties the knot. Stated as the youngest daughter of Richard Ward of Whinney Heys (Hardhorn with Newton), she marries Peter Sykes an innkeeper from Liverpool.

In January of 1856 Mr Robert Cooban of Whinney Heys (Hardhorn; New Whinney), died suddenly aged 45 (parish records give ‘Layton’ as his address and give his age as 47 years.) It is not known what status or occupation Robert had at the farm but on the 1841 census he is living at Bradshaw Lane Goosnargh with the Wards and is of independent means. Hecame with the Wards to Whinney Heysand is living there at the time of the1851 census(when he is described as Robert Cowburn), a nephew of Richard Ward; both Richard and Robert are born in Treales), while it was in the occupancy of Richard Ward. The Cooban name is relevant to the earliest history of Blackpool, Laurence Cowbourne owning land in Freckleton and Bispham. It is first seen in the parish records in the Fylde in 1669 with the baptism at Bispham All Hallows, of Jennet Cooban, son of Thomas Cooban resident at Revo(e), itself a farmhouse on a rise a little inland from the sea before the industrial age which caused the expansion of the town of Blackpool and created a working class area at Revoe, a thorn on the side of the politically orientated Conservative town. From then the Cooban name appears quite regularly across the Fylde until it becomes less common before proliferating in Liverpool from the first decade of the 19th century.

It seems that Richard Ward died in March of 1854 aged 76 and was buried in St Michael’s Kirkham, ten years before his wife Betty who lived until October of 1864 and was buried with her husband at St Michael’s too, age 88.

The demise of the Bamber name left the tenancy vacant and it was filled by Richard Rogers and, after the death of Richard Ward, New Whinney Heys was occupied by James Lewtas.

RICHARD ROGERS 1854 – ?1856

Richard Rogers took out the tenancy of Whinney Heys after the Bambers sometime in the early 1850’s. He wasn’t a local man and probably didn’t live there at least all the time. If the census for 1851 is to be taken at face value, and resident in Blackpool, he originated in Buckinghamshire and thus shares a connection with the Whittaker name which arrived later on. He had also spent some time in the United States if the same census is to be believed as his daughter Elisabeth, if a natural daughter, had been born there nineteen years previously. Not only was he a farmer of over 200 acres at Whinney Heys, he was also a schoolmaster and ran a school in Blackpool. He’d been a teacher since at least 1841 and had been in Blackpool for at least eight years. The school was situated at No 1 Chapel Street in Blackpool with an open view to the sea at the time, prior to the explosion of the development and expansion of the town. From this coastal position he would have witnessed the numerous bodies washed up on the shore in the early Autumn of 1848 from the tragedy of the Ocean Monarch, shipwreck of Titanic proportions. He may have even been one of the many curious folk who went to view one of the bodies laid out the workshop of Mr, …. the plumber who had brought the mutilated and decomposing body of an unfortunate male passenger off the foreshore. He would have seen the town lighted with gas for the first time, in the beginning with vegetable gas then the more economical coal gas. He would have witnessed the onset of the self determination of the town now called Blackpool from the 1848 Sanitation of Town’s Act. He would have seen the filthy streets covered in sewage and the blood of the butchers’ produce cleaned up within the construction of a sewerage system and local laws to curb nuisances. In 1851 he lived with his wife Millicent as the Governess and daughter Elizabeth a teacher in a town that was over spilling with trippers encourage by the cheap tickets of the railway companies. As well as a family of seven children there were 38 pupils of high school age, two assistant teachers, a cook, nurse, housemaid, laundress and boots. They were mostly locally Lancashire, though two brothers were from as far away as Brazil.

With an address at Whinney Heys Farm, a property he most likely rented out to take advantage of the profitability of farming, there are two recorded incidents connected with Richard Rogers there. In the first, horse breeding was an important and profitable business and Whinney Heys had a reputation for producing good shire (heavy) horses. It seems though there might have been some jealously vindictive, or purely destructive and insensitive folk around as in October 1854 ‘some fiends in human form’ stabbed and killed a mare belonging to Richard Rogers of Old Whinney Heys Farm. They hadn’t stopped at killing the animal but went further to break as many gates as they came across, and pulled up a crop of turnips and threw them into a pit. To injure or kill a horse was indeed a severe crime of the time as horses were a man’s best friend and without which you would have to walk everywhere. It might be equivalent today to trashing an expensive car though without the more comprehensively warm sentiment shown to a living animal. The effects would be the same and would incur the same relative costs, investment and even possibly loss of employment.

It’s not known why or who carried out the attacks but there is a possible motive in a court case some years earlier, involving Richard Rogers over the theft of some small items of his property. This case involved the theft of a table cover, a pillow case and a single handkerchief which had been put out to dry on a hedge at the farm. The case was tried at the Preston Quarter Sessions, when it was claimed that they had been taken by 21 year old Ellen Newsham on the 28th December 1844. Though she denied the charge she was nevertheless found guilty and sentenced to two months of hard labour in the House of Correction. Perhaps if there was a niggling and lasting sense of injustice there was a need to avenge by some sympathetic hands or maybe, on an entirely different slant, in his status as a schoolmaster he had annoyed one of his pupils who might not have been too closely connected with country lores and harming an animal only seemed like damaging a bit of property to hurt the wallet of the owner.

JAMES LEWTAS c 1854-1866

The Lewtas family name was a Fylde name of farmers and took over New Whinney Heys after the death of Richard Ward. There appears to have been some infighting however within the family, perhaps jealousies, or other reason as, in 1837, before they arrived at Whinney Heys, some farm buildings which were the inheritance of James and Richard Lewtas had been burned down by both James and George Lewtas. Ultimately James Lewtas pleaded guilty and was declared ‘mad’ on a doctor’s evidence. In 1842 the death of 34 year old James Lewtas is recorded at the Asylum in Lancaster, Lancaster Moor as it was known later. It was a condition that probably could be better understood today and probably it was something that could be treated or cared for now.

It appears that the James Lewtas of Whinney Heys married Ellen Porter at St Michael’s in Kirkham in February 1816. With some status in society as a farmer he had been appointed a church warden at St Michael’s Kirkham in 1847.

There was the Lewtas name in Blackpool in 1900 as Lewtas and Sons with premises in Exchange Street and selling high class coaching horses for waggons and high class carriages and broughams, and ‘vanners’ and ‘bussers’, presumably colloquial names for those horses pulling both the omnibuses and the vans.

In 1853, the year before James took over at Whinney Heys, and while he was residing at Singleton Lodge, in the severe and well recorded storms of January this year, where Whinney Heys would have been safe from the incursions of the sea which reached far inland, and which had continued from the storms of Christmas Day of the previous year, James Lewtas of Wardless (Wardley’s Creek), lost a barque called the Hope after its unloading, and while it was being checked by customs in Fleetwood harbour. His boat had been built at Wardless and it was rendered a complete wreck, being washed over to the Knot and pushed and pulled from place to place by the ensuing tides. The customs officer on board was eventually dramatically rescued and the captain of the vessel was able to wade out on a later, receding tide to collect his valuables and everything he owned.

In May of the same year his workmen killed a total of 400 rats from underneath two stacks of hay as they were removing the wheat crop from the field to the barn, but in 1854 James Lewtas left Singleton Lodge and moved to Whinney Heys. Singleton Lodge was up for let and was classed as a ‘desirable Corn and Dairy Farm’ of over 243 acres with outbuildings, offices, gardens, meadow pasture and arable land.

It is a time now when the agricultural shows were becoming the place to be seen with your produce and being the inspiration and motivation to create the best and be seen to be the best. In the Fylde Agricultural Society Show of September 1855, James Lewtas of Whinney Heys won 10s (50p) as second prize for his mangolds.

In 1857 however, tragedy struck as James Lewtas, the 26 year old and youngest son of James Lewtas snr died at Whinney Heys and in 1864 Ellen Lewtas dies in April of this year aged 74. This may be the trigger for James to give up farming as, in 1865, Mr James Lewtas of Old Whinney Heys retires from the farming business and sells off his farming equipment and working animals. Two auctions were held, the second one being in January 1866. Farming is on the cusp of mechanisation. His equipment included 6 carts, a threshing machine, weigh beam, weights and scales, containers for meal loads, stack cages, horse harnesses saddles and bridles, spades and other smaller items and even a wooden bridge for crossing streams and ditches. Dairy equipment included a churn and cheese making paraphernalia, and there was plenty of farm produce which included a haystack, 100 loads of fluke potatoes and 20 loads of fluke potato seeds, fluke potatoes being ones which produced a good number of tubers. Included also his household furniture which consisted of 4 pairs of bedsteads and four feather beds, cupboards and iron fire grates and oven. He had for sale 31 horned cattle, five horses and colts and husbandry implements, 3 drape (no longer milking or calving) cows, 3 ‘excellent’ work horses and a mare suitable for saddle or harness and a very good trotter.

Later in 1866 three cottages owned by the Oddfellows in Kirkham were up for auction one of which was occupied by Richard Lewtas. There was a James Lewtas on the committee of the Fylde Board of Guardians in discussions concerning the proposed increased salary of the rates collectors in the district.

In 1868 James Lewtas jnr married Ellen Seed of Preston at Poulton. His address is given as New Breck House, Poulton.

James it seems died in 1870 aged 77 and his address is given as Preston but buried in St Chad’s Poulton. The name continues in the Fylde as in 1896 the death of James Lewtas, yeoman, residing at the Grange, Hardhorn, is recorded in 1896.

PARKINSON c1856-1883

When Richard Rogers left Whinney Heys, it was Roger Parkinson who took over. Roger Parkinson is a name associated with the Fylde, most especially Cockerham from 1600 and later from St Michael’s on Wyre.

On Christmas Eve 1840, Roger had married Mary, the daughter of Richard Ward, keeping farming in the family as it were. A son Roger was born in 1856 and who married Mary Dagger at St Chad’s in 1888. He is a farm labourer in Staining at the time.

Roger Parkinson was well known for the quality of his stock and won several prizes at the annual agricultural shows. In 1856, at the Poulton Agricultural Society’s meeting he won first prize of £1 for a bull calf. Farmers were influential members of the community until the spread of urbanisation in the Fylde. They can be found serving on the Boards of Guardians and elected as churchwardens. Roger Parkinson was no exception and in the same year of 1856, he was appointed churchwarden for Hardhorn.

The following year at the Royal North Lancashire Agricultural Association event held at Lytham Hall he won a joint second prize for a mare, ‘for road or field which had produced a calf or was with foal in 1857.’

In 1860 at the Fylde Agricultural Show, the turn out wasn’t as good as it had previously been. This is because the tenant farmers didn’t consider the prizes of high enough value to consider entering their animals or produce. At this Show, Roger Parkinson was the director of bulls and cows. Many regular names however, were represented including Fisher of Layton Hall, Braithwaite of Weeton, Dewhurst of Hardhorn, and MP (for Blackburn) W H Hornby of Mains Hall, all these names wining prizes.

On the 1861 census, 44 year old Roger Parkinson was the farmer of 200 acres at Whinney Heys. With his wife Mary, they had five sons and three daughters and employed five people.

In 1862 there is an interesting little anecdote regarding Roger, the six year old son of Roger snr who had deposited a halfpenny in the privy. He had swallowed it two years earlier and it had taken that amount of time to travel through his digestive system. The newspaper snippet was headlined, ‘A hard morsel to swallow.’

At Old Whinney Heys farm, one of Roger’s horses, a spirited youngster in the team of two horses, was a bit wild and got itself pierced in the breast by the harness of the second horse. It penetrated twelve inches deep, inflicting a ‘fearful orifice’. However Roger Parkinson called in the vet, and the skills of Mr George Hutchinson of Marton saved the valuable horse it being well again after a month. George Hutchinson lived with his wife, daughter and son at Top o’ the Town, Great Marton. His son trained to follow him into the profession.

By 1864 Roger Parkinson is secretary of the Farmers Insurance and Protection Society which had over 500 members and 7,000 cattle insured with them. Cattle disease is a perennial problem and the insurance was the ‘peace of mind’ it always portrays itself as.

By 1868 he was back into his winning ways and in August of this year at the Blackpool and Fylde Agricultural Association Show, ‘Roger Parkinson of Whinney Heys’ won a prize for ‘three cows in calf or milk,’ and by the 1871 the family is still at Whinney Heys, a farm of 212 acres. There are six children at home ranging from 24 to 10 years old. By this year he is also a member of the Kirkham Board of Guardians.

In 1872 at the Blackpool Agricultural Show held on the large field at the Raikes Hall Park and Aquarium Company, Roger Parkinson of Whinney Heys was a judge of the vegetable exhibits. A gelding for harness of his also won first prize later on in the animal shows and he also won first prize for the best pen of geese. Many familiar Blackpool names were among the exhibitors. Jonathan Read (of baths and market fame) won first prize for the best load bearing cob. At the end of this show there was a steeple chase around the field. For a £15 prize, it proved a disappointing event. With three horses participating all the riders were thrown off on the first lap but ‘Miss West’ went on to be awarded first prize. None of these horses were locally owned.

At the Great Eccleston Agricultural Show of 1876, Roger Parkinson of Whinney Heys was a judge of roots and pigs, and in April of the following year of 1877 Roger Parkinson and John Fisher (of Layton and who provided competition for prizes in the various Agricultural Shows you would imagine) were both as judges in the Fylde District Agricultural Society Show in the grounds of The Raikes Hall Park Garden Company. He is also a judge at the Great Eccleston Agricultural show of this year.

In 1879 at the Great Eccleston Agricultural Show in September, Roger Parkinson won prizes for a ‘two year old gelding or filly for road or field’. Still winning prizes in August of 1881, 64 year old Roger Parkinson of Whinney Heys won prizes for cheese and butter at the Blackpool Agricultural Society Show at Raikes Hall. On the census there are only Roger himself and two daughters at home as well as a domestic and two farm servants. The Blackpool Agricultural Show was the new name for the Fylde show as Blackpool’s influence gradually swallowed up the smaller districts. It took part at the Raikes Hall Park.

On the electoral rolls of 1882 and 1883 Roger Parkinson’s address is given as Whinney Heys, Hardhorn-with-Newton. Mary had died in 1880 and Roger died in 1883. Both are buried at Poulton St Chad’s. After his death, Whinney Heys is once more up for let. ‘A very desirable Dairy and Corn Farm containing over 204 acres.’ A short obituary in the Blackpool Herald of July 1883 states, At the age of 66, another member of the Fylde Board of Guardians has gone to the rest that remaineth for all. Roger Parkinson, who has farmed Whinney Heys for over thirty years, was buried in Poulton churchyard last Saturday. For some months he had been confined to the house.’

BRAITHWAITES 1866-1887

The Braithwaites (who also farmed at Mythop sometime after the Gratrix’s), had an original association with Rossall Hall. There are many Braithwaites in the records and the name goes as far back as the 17th century in the records of the Fylde and its environs. The Braithwaite name, strong in Hawkeshead, first appears in the Fylde (Bispham and Marton) from the second decade of the 18th century on the parish records and from then begins to proliferate in the Fylde, in Marton and Bispham, and Layton Hawes as skilled craftsmen. George Braithwaite is a servant at Layton Hawes in 1821. John Braithwaite is a yeoman in Bispham in 1821. In 1828 a John Braithwaite aged 28 shot himself by accident. By the 1830’s Richard Braithwaite (wife Betty) is a butcher and has an address as Blackpool in 1838/9. John Braithwaite, a butcher also, in 1847 and John and Betty Braithwaite, innkeepers, in 1849. In 1861 John Braithwaite and Alice are living at Mythop where John is a farmer. On the 1851 census John Braithwaite is at the Fleece Inn Market Street in Blackpool with his wife Betty and two daughters with two house servants. In 1861 Thomas Braithwaite and his wife Hannah now keeping the Fleece Inn. In 1868 a John Brathwaite married Ellen Breakell.

From 1846 with the arrival of the railways, the collection of dwellings and inns on the coast referred to as Blackpool began to grow and the land that was used as farmland for grazing or cropping became more important as building land in which the greater profit existed. There was interest then in the profiteers from the burgeoning town to take advantage of the countryside and also interest in those in the farms who saw greater profitability in the towns. The Braithwaites had an interest in both as the opportunity afforded itself. The livestock of the farm at Whinney Heys, was the meat produce sold in the butcher’s shop on Market Street in the town.

The Braithwaites moved in to New Whinney Heys and were contemporary neighbours of the Parkinsons. The first mention of the Braithwaites name at Whinney Heys is 1866 and the last is John Braithwaite aged 62 in 1887. Like his neighbour Roger Parkinson he was proud of his stock and produce and in the September of 1869 in the field of Mr Dagger at Raikes Hall, Mr John Braithwaite of Whinney Heys won second prize for the best farm of between 80 and 150 acres, ‘in the most approved state of cultivation.’ Roger Parkinson of the other Whinney Heys won a second prize for a pair of agricultural horses and a recommendation for a ‘colt or filly’.

In March of 1870 a ploughing competition took place at Singleton, on behalf of the Singleton Ploughing Association after which refreshments were served at the Miller Arms when a Mr Braithwaite of Mythop was chairman and Roger Parkinson of Whinney Heys was one of the judges. There are 19 entrants, 16 men and three boys and all showed the most competent of skills, making the judging difficult. A Richard Braithwaite won first prize for the boys’ entrants. These were all very male affairs but among the many after speech, self-congratulating toasts, there were two for the women which included one for the Queen and one for the hostess, whose hard work in the provision of the meal was at least recognised. The servant girls didn’t get a mention but might have had an imaginative pat on the bottom by the mildly lasciviously inclined in their perceived dominance or confidence of drink, and that’s all the attention they might have received. In the same year a great exhibition of agriculture took place at both Layton Hall and Whinney Heys Farm, a walk or a short ride away from each other.

The week before Christmas of 1870, witnessed a road accident, Victorian style involving a horse and cart (described as a shandry) while John Braithwaite and a ‘servant’ man were travelling back to Whinney Heys from Thornton. The horse became spooked for some unknown reason and set off at an uncontrollable gallop by the Carleton railway crossing and the two men were both thrown out leaving the cart and horse to race forward unattended. Mr John Dewhurst coming in the opposite direction on horseback seeing the incident called to a farmhand named Bamber on Mr Poole’s farm nearby to open a gate to let him in out of the way of the runaway horse. He had only just got inside and the gate shut when the horse with its shandry collided with it smashing both gate and cart. The cart was stuck in the gatepost and the horse could not continue further but shied frantically in its panic. A large piece of wood had been thrown from the gate and hit Mr Bamber on the head rendering him unconscious. A doctor was called for and he soon recovered. John Braithwaite and his companion were unscathed but a little shaken.

Preston Chronicle August 1870

In the same year, Blackpool’s annual Regatta, was postponed several times due to inclement weather but eventually took place in July. Crowds filled North Pier to view the event. Blackpool was now becoming a focal point for events which attracted large numbers of people who could easily reach the growing town via the railways.

It was also a time of booming land prices and if there was a bit of money spare the canny capitalist would invest in land. In an auction announcement in 1875 in the papers, for sale of land in both Marton and Layton with Warbreck, John Braithwaite of Whinney Heys appears to be one of the sellers.

The land has its sad stories to tell however as long as it is walked upon by the human being. In late June of 1880 and in a field belonging to Mr Fisher near Whinney Heys, a man called Burke had seen some clothes by the side of a pond and had informed the police. On investigation the body of 22 year old John Whiteside, a labourer of Raikes cottages was pulled out. He was a married man and had been in ‘low spirits’ for quite some time. Within the perceived idylls of the countryside there are nevertheless the contortions of human relationships and the confusion of self-awareness.

In July of this year Arthur and Mabel Braithwaite, children of John and Mary Braithwaite of Whinney Heys, were baptised at Bispham All Hallows.

In 1882 Abel Braithwaite, son of John Braithwaite of Whinney Heys, emigrated to to South Africa (Natal) and worked in a sawmill making timber sleepers for the construction of the railway northwards. The Zulu War had been concluded a couple of years earlier and the Zulu Chief Cetawayo captured and imprisoned. However, Abel Brathwaite is concerned in his letters home that as there was talk of Chief Cetawayo being released and returned to Zululand in a reorganisation of the South African districts and that because of this, there might be another war. It was a white man’s world and the indigenous Africans were referred to with the complete disdain of the ‘n’ word and beaten with sticks to make them work if there was a language problem. While, after the war, the compliant Zulu chieftains were given each given a territory to keep then disunited, one of them, quite paradoxically a Scotsman, John Dunn with an ‘awful tan’ (Abel Braithwaite’s description) and who kept four white wives and twenty black ones would not be happy to see the Zulu King on his territories. Such is colonialisation. Human social evolution moves on. Sometimes it improves. Sometimes it regresses.

Still at Whinney Heys in September of 1883, George, son of John Brathwaite of Old Whinney Heys married Mary Hartley of Southport.

In 1885 the owner of much land in the Fylde, a Mrs Dawson who had inherited the estates as heiress from Thomas Oxendale of Preston, and which included both Old and New Whinney Heys, had died and the properties were up for sale by auction. Situated in Layton-with-Warbreck and occupied by John Braithwaite Old Whinney Heys (112 acres) sold for £5,700 at a rental of £184 (I guess pa) whereas the 216 acre farm New Whinney Heys was withdrawn at £8,600. The estates were sold off piecemeal.

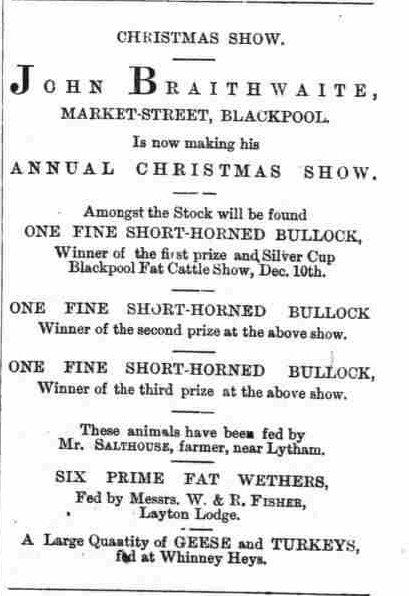

1887 was the year in which John Brathwaite died. He died at the end of April at his home at Whinney Heys where he had lived for the last 23 years and was 62 years old. John Braithwaite was a prominent member of Blackpool, being one of the first Councillors elected, and represented Claremont Ward. He had been involved in all the early and first improvement works of the town. His father Richard was the first butcher in the town and John continued this trade supplying the town with meat for over 40 years from his shop on Market Street which he had occupied for about 35 years. The funeral took place at Bispham Parish Church. The Braithwaites had been around a long time in the district, a John Braithwaite, yeoman having been recorded as farm bailiff at Rossall Hall in 1711. From there he moved to Layton Hawes. His son Thomas, yeoman at Layton Hawes had a son Richard reputedly the first butcher in Blackpool. John Brathwaite was the eldest son of Richard being born in 1825.

So, in 1887, also in August of this year, the freehold estate known as the ‘Old Whinney Heys’ estate of 99 acres is up for auction and formerly in the ‘occupation of John Braithwaite until his death’. It seems to be the closure of his estate as a house and butcher’s shop as well as a slaughter house in his occupation at 22 Market Street were also some of the many lots as well as much property in Blackpool including many shops and houses in Braithwaite St and Upper and Back Braithwaite Streets, as well as shares and debentures in some of Blackpool’s utilities and estates and Over Wyre in the Shard Bridge Company.

Shard Bridge provided a good opportunity of investment for someone with a bit of spare cash and an eye for increasing the return on that investment. A bridge across the river Wyre, to replace the ferry and to open up the Over Wyre district would probably have been a sound investment. A bridge and a road to connect it from Mains Lane was first proposed in 1845. The project would cost about £5,000 and John Braithwaite would have been one of the multiple shareholders (£10 shares were originally issued). By April of 1863 the plans for the bridge had been approved by the Board of Trade and the work on the bridge could now proceed, the construction engineers being Messrs Fairbairn and Co of Manchester. It had been completed by 1866 when a regatta and party were held by the Shard there. It’s possible that John Braithwaite and family were there enjoying the day out with their picnics and entertainments and boat race, a duck hunt and aquatic sports. There was drama, too as five lads stole a boat, capsized it and nearly drowned before they were rescued. But the busiest place was the Shard Bridge Hotel ‘where both sexes were doing their utmost to amuse themselves,’ a statement which lends much to the imagination.

There was plenty of opportunity for investment n Blackpool – the new Council were always in need of money for sewerage, water, sea defences etc. those who had money had the means to invest and accumulate. ‘It is now marvellous to witness the rapid development that this seaside resort is making. The farm attached to Layton Hall, formerly one of the richest and best managed holdings on the Fylde, is now being yielded up to the advance of the builder’. Preston Herald 1896. Once owned by the late John Fisher, the farm was renowned for the quality of its crops and the breed of its horses. By 1896 it was owned by a Mr Lumb of Halifax and a Mr Worthington of Blackpool and extensive building work was well under way. Whinney Heys would be able to see the urbanisation creeping nearer and nearer like the terminal saw that crept nearer and nearer to Vera in the popular rhyme.

This is now the period of the smaller tenant farmer, and more farms of smaller sizesof ten acres or so and it was the beginning of theuneasy neighbour relationship with the advancing towns. Some of the dairy work of the farms was being taken over by the large creameries which produced butter and cheese, traditionally made by the women of the farms. When a creamery at Garstang was proposed by the Co-op, a collective to which the farmers of the area would sell their milk at a low price, the argument against it was that the conformity of the butter and cheese it would produce by taking milk from a wide area would take away the uniqueness and varieties of the taste and qualities of the butters and cheeses made on the individual farms and which the farmers could sell at their own price at the markets. ‘What shall we do with our daughters if all the milk is taken to a creamery?’ bemoaned a Staining lady to the correspondent.

The numbers of trespassers were also increasing. ‘Especially near Blackpool is the nuisance aggravated. The marauding seaside tripper, out for a day’s lark, takes a walk in the country, mounts the hedges to their detriment, leaves gates open, chases livestock, tramps to his heart’s content amongst the green crops and, if spoken to by the farmer, generally adds to his offences by his impudence’, writes the correspondent of the Preston Herald in the July of 1896.They would also idly pick mushrooms for which the farmer could otherwise get 9d (7½p) and a yield of £30 (over £3,000 in 2020) for the season if lucky.

In this same year of 1896 the newspaper article resonates with the state and condition of farming of the time. There had been a drought for the first part of the year followed by a heavy downpour of rain which largely ran off the parched earth rather than being absorbed by it but, despite this, there was nevertheless a good harvest of hay in the Fylde.

The relatively high price of labour was a bone of contention with some of the farmers. A man who could handle a team of horses to follow the plough cost 26s (£1.30) to 28s (£1.40) a week. An itinerant Irish labourer would cost £1 and all the porridge he could eat and would usually be engaged for a month in the harvest season and come rain or shine he would be found work of any kind on the farm and fulfil it competently. They had come in handy before in Blackpool during a fight between two warring farming families, the Kirkhams of Warbreck Farm and the Banks of Scut House Carelton, the presence of the Irish labour being on hand to discourage further violence from the Kirkhams.

Of course when the tenancy of a farm was on the market there were jealousies and infighting in order to get to the farm from one that was perhaps not as profitable or was in the hands of a more reputable owner. Tenants of course, could be evicted if proved unsuitable or agitating with too much complaint about the rentals imposed by the owners or their agents. Unless there were some corrupt practices and behind the scenes prejudicial jiggery-pokery, CV’s would be brushed up, collars stiffened, the best Sunday suit put on and a supplicant manner adopted for any interview that might take place with the owner.

The Fylde had a an excellent reputation for breeding all kinds of working horses and Whinney Heys was up with the best, the Fishers of Layton Hall, and a Mr Sykes of the Breck, Poulton in the latter half of the 19th century. Buyers came from all round the world but especial interest was given from buyers across the ‘Herring Pond’, as the Atlantic Ocean was colloquially referred to (though sadly with a reflection of the slave trade), in America who bought everything and anything but most especially the shires with their reputation. The popularity of the horse sales had however already begun to wane as the figures of horses presented at the show and sale had diminished considerably since the peak year of 1889 when over 1,000 animals were entered. The 20th century brought in mechanisation and motor cars and so signalled the demise of the horse as a valuable working animal and by 1925 at Whinneys Heys there were only stables for leisure and horse riding with an address on the road that took its name from the former landed estate, thast large and prosperous farmstead, reduced to the smaller farm renowned for its horse breeding, and latterly, just a small farmhouse before its eventual demolition in 1969.

DEWHURST c1885-c1896

The Dewhursts were a Fylde, farming family. As well as Daniel at Whinney Heys at this date there was also John Dewhurst a‘progressive young farmer’ who had learnt his profession well at Whinney Heys, down the road at Staining Farm, owned by W H Hornby influential Conservative and former MP for Blackburn, though with Blackpool connections (the Hornby family occupied Raikes Hall from about 1826 to 1860), and one of whose sons, Albert Nielson Hornby, was captain of the England cricket team on the occasion of losing to Australia in the Test Match that created the Ashes. William Henry Hornby died in 1885 and two sons continued his career. So farming was still for socially influential and successful people not just for the rough and ready character proud of his blunt sentiment and undecipherable, local accent.

Daniel Dewhurst sold a large quantity of milk in Blackpool daily. Milk kitting was a staple occupation of the farmer and the milk and its products of butter and cheese would be sold at Blackpool market. However, in May 1896 John Greatrix of Fair View farm Poulton encapsulated the dilemma of the Fylde farmer in selling his products in town, bemoaning the fact that there was much foreign produce coming in at a lower price and he had to drop his own prices to the very lowest margin of his profit. There were the creameries which would take the milk in bulk but the price paid was meagre.

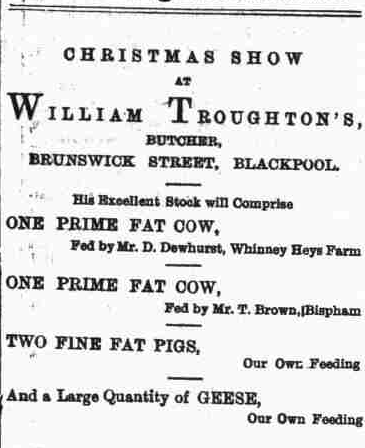

In 1885 Daniel Dewhurst was already in occupancy of the farm known as ‘The New Whinney Heys Estate’ as it went up for auction. This may be on the death of William Hornby who had died in 1884. Much of his later occupancy was during the ownership of James Fish, a self-made man who was to become a mayor of Blackpool, when ‘Mr Dewhurst’ was the farm bailiff there, a farm of 220 acres, 60 of which are arable and treated on the ‘four course system’. This meant growing crops, three food crops and a grazing crop which was grass or clover, so that cattle and the all-important horses could be bred all year round. There was an excellent market for straw and hay in that system, with clover hay selling at 5¾d (less than 5p) a stone ( a little more than 6 kilo) and meadow hay about 5d, a little less again. The land around Whinney Heys ‘is excellent for sheep though 1896 had been a bad year for grass.’ The produce had its own individuality and each and taste and quality in meat and dairy cold be identified as being from the different farms as this butcher’s advert from a Christmas 1888.

According to a reporter from the Preston Herald who had visited the Fylde and the farms of the Dewhursts of Mythop and Whinney Heys, Mr Dewhurst of Mythop had raised the fine mare, Jolly Lass (fathered by Jolly Tom so quite a jolly lineage and owned, by the reputable Mr Sykes, a kind of king of the breeders, of Breck, Poulton) which was grazing in one of the fields. Recently she had injured her foot prior to which she had never been out of the show ring without a prize. She was still foaling, being served by Mr Forshaw’s stallion, Orchard Prince. Mr Dewhurst had a fine stock of horses in the stable boxes too.

Shire horses for which the Fylde and Whinney Heys were renowned at one time was a much more profitable line of horse breeding than the ordinary hackney horses and they could fetch a much better price. Also on the farm there was a dairy herd of ‘pail fillers’ which provided enough milk to warrant twice daily journeys to Blackpool to sell. The dark roan bull which served the cows to produce dairy and butchers’ products was an Oxford Rose and was just one year old. All in all the farm of Mr Dewhurst at Mythop was a successful, well run and profitable one.

The correspondent of the 1896 Preston Herald then went on to visit the farm of the other Dewhurst, Daniel at Whinney Heys and found that he had just got over a bout of serious illness. At Whinney Heys Hall of over 200 acres, 22 of these were taken up with excellent hay. His wheat, oats and barley were also of a very good quality. The weather hadn’t favoured his root crops to date but there was still time for improvement before harvesting. He sends about eighty gallons of milk a day to Blackpool in summer and about 30-40 in the winter months and his prices are double that of the milk bought by the creamery, that new idea fresh in from Ireland of a collective buyer which produced a conformity of output of butter and cheese, differing entirely from the individual tastes and consistencies of the individual farms.

One of the perhaps unique features of the farm was the pond which was rented out to the Aquarium at Blackpool. The fish from there were brought to the pond for an ‘airing’ by the Aquarium, and left there for a considerable time before being taken back to the glass cases of the Aquarium building to delight the day trippers.

As well as the arable land, there was a field of ewes which had produced 80 lambs this season alone and many of which were ready for the butcher’s knife. In the same field were some horses, some of which were famed and had won several prizes in the local and county shows and beyond.

On the 1891 census there is a James Dewhurst as the farmer at Watson’s Farm at 314 Lytham Road. In this year Daniel is living at Whinney Heys with his family, which included his wife Ann, sons James and Thomas and daughters Margaret and Mary and three farmsevants. He had married Ann Fairclough, of a farming family, in 1860 at Poulton St Chad’s.

In 1891 at the Blackpool Agricultural Show a prize was won for a three year old draught horse sired by one of his own horses. In 1892 he also won a first prize for a ‘three old filly or gelding’. The next farms along are Dawson’s farm and then Atkinson’s farm. Daniel is on the electoral rolls for this year.

In 1893, the members of the Lytham, Kirkham and Blackpool Agricultural Society put on their annual show in Blackpool at the Royal Palace Gardens, Raikes Hall, on spacious land ideally suited to the event. It was a fine day but the ground was soft and wet beneath. It was a focus of attention for the farming industry and for locals and more distant entrants. Mr Daniel Dewhurst of Whinney Heys won third prize for his brown shire horse, Jolly Lass. He also collected prizes for a smaller brood mare, (breeding horse) and a yearling gelding or filly.

By 1896, at the Little Marton Horse Society show held, not surprisingly in Little Marton, in September of this year, there was not a very good show of quality apart from the exhibits of Mr Sykes of Poulton who had won every show he had entered his horses into recently. However a heavy horse, a brown mare shown by Daniel Dewhurst of Whinney Heys, (once more described as in Staining), came reputably close. It was a disastrous show as when luncheon had been prepared in a large marquee the wind blew strong and ripped it up as well as turning over all the tables and so those who wanted anything to eat had to be accommodated at ‘a nearby hotelry’.

Also in this year, at the Blackpool Agricultural Show, the committee of which had Daniel Dewhurst on its books, he won a prize for a short wool ram. The Summer months were a busy time for farmers to show, and also in this year, a correspondent in the Preston Herald, describing a stroll through the Fylde, says this about the crops of Daniel Dewhurst of Whinneys Heys, ‘Wheat looks extremely well and on the farm of Mr Daniel Dewhurst, at Whinney Heys, I saw a grand field of this crop as could be found in the Fylde.’ The best crop of wheat in the Fylde.