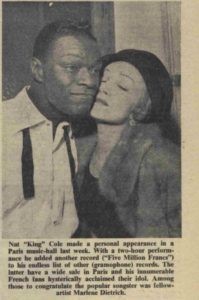

Victoria Monks Musical Hall Artiste

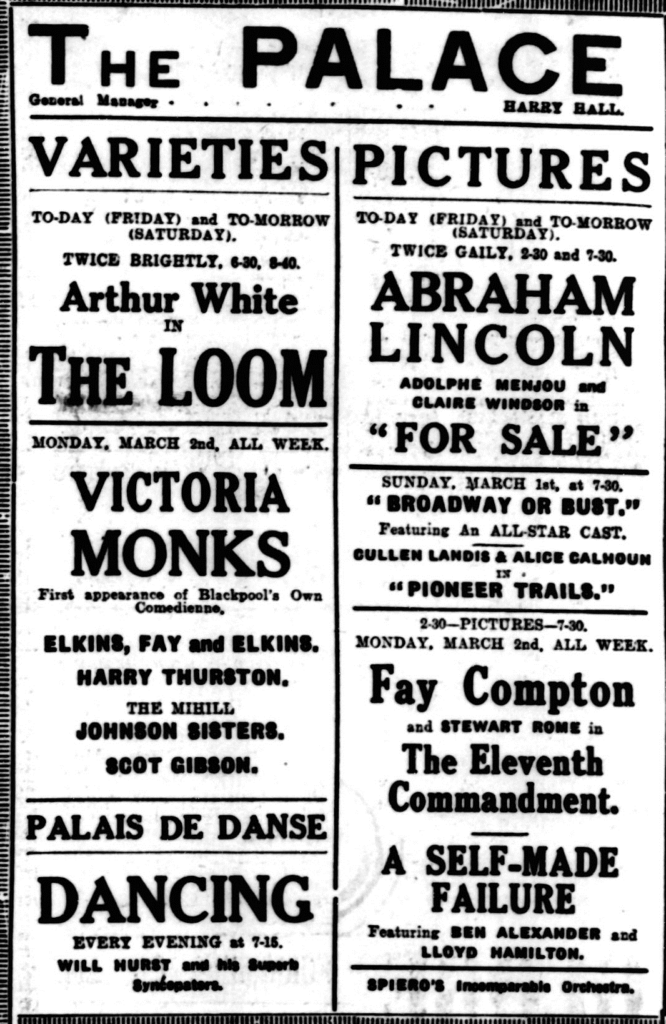

Victoria Monks was born Anne Monks in the district of Revoe, Blackpool on Nov 1st 1882 and, at a young age, found popularity and then lasting fame in the Music Halls during her lifetime. From the 1890’s to her death in 1927 Anne Monks, eventually as Victoria Monks, was on the stage at various levels of popularity, sometimes extremely high and sometimes extremely low. She invited much controversy in her private life, often providing good substance for the newspapers. In her role as celebrity, and with less publicity, she was involved with raising funds for charitable concerns, kicking off charity football matches, and contributing to appeals for soldiers’ comfort funds (cigarettes etc) during the War. Eulogies after her death describe her as a generous friend to her fellow artistes.

Victoria Monks was evidently a naturally talented artiste with an excellent stage presence and an artiste who knew how to connect with the audience. Her private life, however appears to have been the opposite, caught up in the wealth and confusion of a high life of popularity without the help of modern day counselling or psychotherapy. Just like many a modern day celebrity, Annie’s true soul remained paralysed within her wealth and popularity. She had a fatalism running through her life which created a difficult marriage with what might seem a difficult husband and which continued after her divorce when her inner insecurity was exposed to the elements. Her original earnings as Little Victoria of £5 (£531.64 in 1899- -another newspaper puts it at £10) per week increased to several hundreds of pounds at the peak of her career, and her most successful phase was the first decade of the century.

When this account was first written, and without an official notification of birth to go on, there had been some doubt about the place and circumstances of her birth, but this has since been confirmed by a view of the birth certificate and revealed by the diligent work of Alison Young, secretary at the British Music Hall Society. The notification of her birth states that she was born in Revoe, which is one of the two ‘working class’ districts of Blackpool. From this Revoe address, the family then moved to Duke Street by the railway line, where Victoria’s mother died and then the family finally established itself at 24 Elisabeth Street where a commemorative, blue plaque, is about to be unveiled and scheduled for 19th April 2024. This event has been arranged and organised for the British Music Hall Society again, via the persistent and careful work of Alison Young over the years. There has also been the evident misconception that Victoria’s mother died as a result of giving birth to Victoria but this is disclaimed by the fact that her mother, Mary Monks, died in 1884. If she had very tragically died in childbirth, the child would have been the seventh in the family.

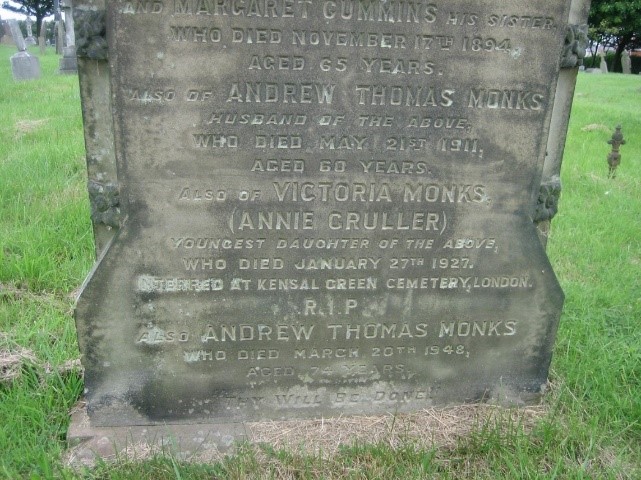

The censuses (seen) can be confusing because, as well as giving different forenames to Victoria’s father, they also give Blackpool and Liverpool as the birth place of both her two elder sisters (and Birmingham and Liverpool for one of her brothers). The family, however, are settled in Blackpool by 1891, some of who are later buried in Layton Cemetery, where Victoria is inclusively commemorated on the family gravestone (though she herself is buried in Kensal Green cemetery, London). She was variously known as Anne/Annie/Nancy/ /Little Victoria/Victoria Monks/Hooper/Gruhler/Groller, (also Nancy Victoria in her earlier, stage days, and even ‘Saucy Victoria’ at one time when the public demand was high and the critics were swooning.) By 1899 she had left the name of Little Victoria behind, to become simply Victoria Monks and the name stayed that way. The Groller of the commemorative gravestone in Layton cemetery, Blackpool, would be expected to be a misinterpretation of Gruhler (her official, married name). Either the monumental stonemason was drunk or the instructions were wrong. You would like to believe the latter.

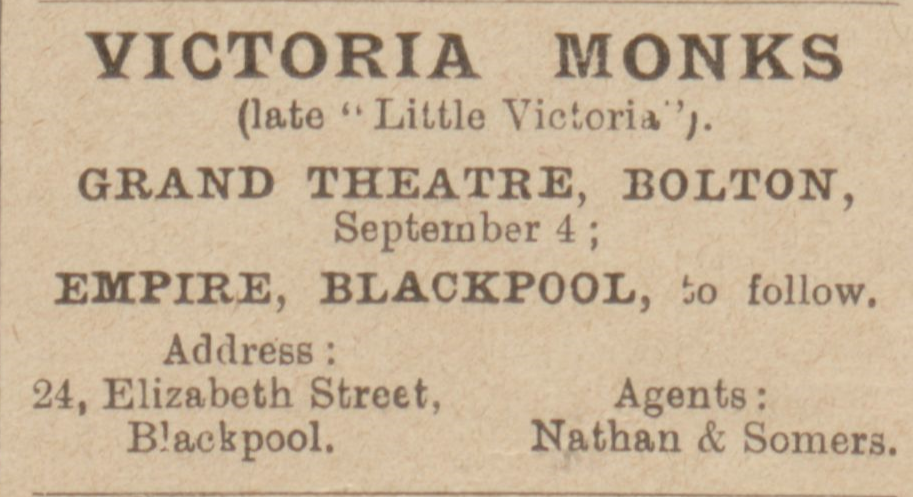

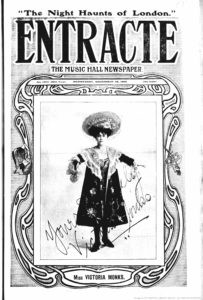

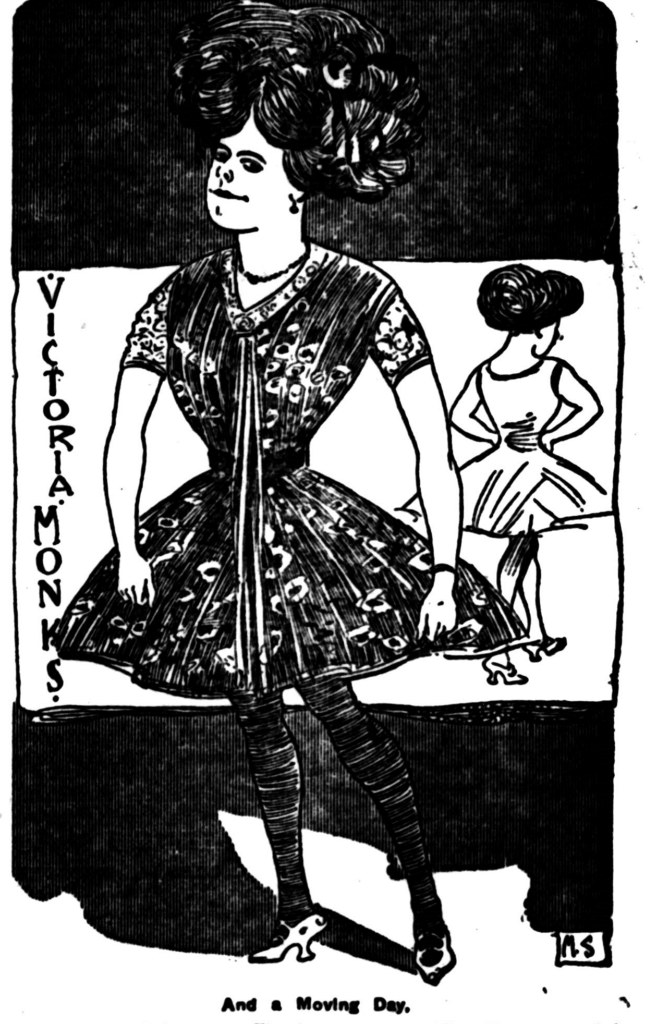

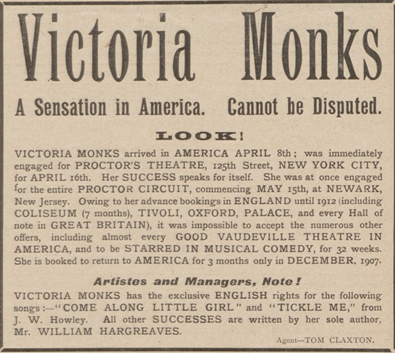

The Music Hall and Theatre Review August 25th 1899. About the time, as a 17 year old, she changed her name as she embarked upon both a career and an adult life.

Anne, was reportedly first on the stage in a dance troupe, often reported as being at the Raikes Hall Gardens and then, in her own professional capacity, as Little Victoria, at the Empire Theatre, Blackpool (the building now demolished – it became the Hippodrome then the ABC, then Rumours night club and now a car park and in process of redevelopment). She was only 11 years old at the time and, in the following years on tour, she was on occasion, accompanied by her two sisters, and her brother who also sang on the same bill. In March 1909 Victoria’s brother, Jack Monks, billed under his own name at the Royal Hall, Jersey, ‘sang in his usual fine style, ‘Turn to the West,’ ‘You Know Very Well What it Is,’ and ‘In the Valley,’ for an encore’. Margaret and Elizabeth Monks were equally and unimaginatively known as Peggy and Bessie Monks and both have, ‘comedienne’ in their descriptions. Indeed in 1901 Annie is living at home at 18yrs old and is a Music Hall artist, and her father is a self-employed optician. In the ‘Era’ publication of October 1901 Victoria Monks’ talents are advertised, and her Blackpool address is given as 24 Elizabeth Street. By now it appears she has a manager who is George Aytoun of London (she seems to have changed managers several times during her career, and left not always on good terms).

As Annie, she appears definitively first, as far as these pages are concerned, on the 1891 census which shows the family living at 12 Duke St, Blackpool, before a move to 24 Elizabeth Street by 1901. Duke Street backed on to the busy, arrival, departure and shunting lines of the (now defunct and demolished) Central railway station of the town. Elizabeth Street is more residential and would have perhaps been quieter, apart from the neighbours, maybe….. It seems Annie attended, (‘passed her early childhood’), in a convent in Warwickshire or in Blackpool… or in Preston…or in Birmingham…or in Belgium…(and more precisely Brussels) or a combination of one or more, if the newspapers are to be believed without question. But a family source states that she went to the Layton Hill Convent in Blackpool. She is also reported to have attended a dance school in Oxford Street, Liverpool and then was a member of the ‘Four Little Daisies and the Coon’ which, if true, might have been instrumental in developing without questioning, her imitative act of the Afro-American persona, as considered quite acceptable in the day. In the beginning of her career as a young girl she could earn £10 (£1,051.32; calculated as in 1892) a week and by sixteen her earnings reached £100 (£10,754.92; calculated as in 1898) weekly. Suggestions of her parents not wanting her to go on the stage are not borne out by her mother’s early death and the fact that three of her siblings, Margaret, (‘Peggy’) Elizabeth (‘Bessie’) and John (‘Jack’) also took up the stage profession, and all lived at home in the early years. It is also stated, that her father was a popular theatrical agent in Lancashire and Yorkshire, though no direct evidence of this is forthcoming to date. Her father is reported to have acted as his daughter’s agent and it is claimed by Olive Plant, one part of the Dainton Sisters who, it is reported, was educated at Breck College, Poulton Le Fylde, that Alfred Monks has procured for her, her first paid engagement. Elsewhere it is loosely stated that her father was on the stage himself at one time, though the only stage apparent in observing his reported history is the ground he is stood on and, in front of him, his audience, those who would be part of his life, close or distant in the turmoil of self-understanding and relationships. There is a family story however, related by Ken Vickers, who has accumulated a lot of material on his great aunt Victoria Monks, that Andrew was in a minstrel band at one time, though just when, or for how long, is not known.

He was however, originally at least, by profession, an optician. He advertised his business in the local papers and had a business address on Lytham Street (now Corporation Street) in the town centre and stalls on the two existing piers of the time. At the annual Arts and Industries Exhibition for Blackpool North West Lancashire held at Blackpool in June of 1891 from the Blackpool Gazette and Herald, ‘Mr A T Monks as was the case last year, has a stand at which everything appertaining to the “optic” may be learnt and all kinds of instruments obtained at very moderate prices.

Victoria’s Character

To impose a modern viewpoint on Victoria’s character especially regarding the genuinely sensitive topic of race relations would perhaps be unreasonable. The Music Halls reflected the zeitgeist of the age and it was a time in human, social evolution where, on the worldwide stage, one race of folk felt they were legitimately superior to another and could consequently patronise, ridicule satirise at will and with impunity. The accent and character of the Afro American of the Deep South was thus ridiculed on the stage and did indeed help to prolong that attitude into succeeding generations. So, while change does happen, even without the associated pain, it is usually agonisingly slow.

In a eulogy from an arts reporter in the Preston Herald of August 1911, Victoria Monks is described as a ‘Blackpool lass,’ before her appearance at the Hippodrome in Preston. She had some new material, but it was expected that there would be a good demand for her old, popular numbers. She is described as unique and cannot be compared or copied. She is not just a singer but also an actor and her songs are contained as much in a ‘one part sketch’. Her talents are extremely apparent and her presentation strong and confident. There is, however, some hesitation or ‘singular disapproval’ of her methods which might refer to her eccentric dances, a directness in her manner, or perhaps to the ‘negro’ content. In some songs she had a stooge – a ‘burnt-cork’ individual.

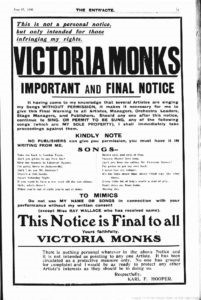

Relying largely on newspaper reports, her character is variously described throughout the decades of her career. To quote the Music Hall and Theatre review of 5th May 1910, ‘Victoria Monks, the moment she appears on the stage, creates an atmosphere that arrests attention. Apart from her attractive and fascinating personality, she is an artiste whose magnetism, artistic methods, and reserve power enthral and subjugate a concourse of human beings at will. The power is given to the few who achieve success, and trebly to those who, like Miss Monks, maintain and firmly hold it.’ She excels in the clever ‘negro’ character songs, but, in this, more specifically those of the ‘deep south’ of North America where the conflict between the races was most evident in its horror. This very real horror did not, it appears, exist in the mindset of those who imitated the same ‘deep south’ manner and accent or those who were entertained by its expression. In contrast to this, in the world she knew, she ‘has a reputation for great kindness of heart and it is well known she is the first to help those who have fallen by the way.’ When asked what her amusements were, she claims it is dogs and horses. She loved animals, perhaps because she could get on better with them than with another human being. In this respect, there was no one to argue with, no one to criticise and no one to whom you had offer your own self-justification of being alive. You are in control of the animals and they do what you tell them, sometimes anyway. According to this continuing review she had in her house ‘an assortment of cats and dogs and parrots, the latest recruit which is a baby goat which is being brought up on a bottle’. Of her dogs, one is called Bill Bailey, the song she is most famed for. Of horses, she claims she can ride quite well and one of her ponies is ‘the best trotter in London not engaged in track work.’ ‘These are my recreations.’ She would have loved to retire to the countryside with her menagerie of pets, ‘But the stage is my life’, and she was most evidently in great demand at the time. Her private life does not get the attention that her very public life does.

Regarding her pets, in May 1914, Victoria was a defendant in one of her several court cases. She had refused to pay an extortionate vet’s bill of £24.11s (£24.55p: approx. £2,341.00). The judge agreed that the vet’s bills were very high and, since Victoria Monks had intimated that she would be prepared to pay a fair price, the judge set the cost at £10.6s.5d (approx £1000.). The dog, a Yorkshire terrier, which had had pneumonia and had developed distemper, was not even Victoria’s dog but belonged to her friend, Mrs Dunville (who was currently on tour in Wales) and with whom she shared her flat at New Cavendish Street in the West End. It was stated during this case that Victoria was fond of horses and dogs (as was her former husband). ‘Miss Monks owned five scotch terriers all named after music hall stars.’

In this Talking Machine review, ‘Her fascination is remarkable, for whatever song she sings, her audience are all attention – no little journeys to the saloon bar for refreshment, for instance. Sometimes she first stands still upon the stage; sometimes merely wanders backwards and forwards,’ and, ‘Like a harp she plays on the mass of people from stalls to gallery.’ The review continues, ‘She is ‘not beautiful even pretty but her face has a fascination often denied to either.’ She had a strong voice but not in any way striking’. At the time of the review it was claimed that she was static on the stage but as soon as she arrives there she has the audience from stalls to gallery in the palm of her hand.

And in the Empire News of 29th November 1908, we are informed that, ‘Victoria Monks is really the sentiment provider to the populace. She generally has her songs set to catchy, easily hummed waltz tunes, she warbles with commanding force, her mighty methods compel all to listen and to hear, and she changes her ditties with commendable frequency. Hit or failure, the repertoire must be regularly altered, and she refuses to cling on to even the greatest of her successes until it becomes a classic.’ At the time this was written it was claimed that she had become tired of ‘Bill Bailey’ and now all London was singing, ‘Come Round Any Old Time’, and she had tired of that too and now was ‘dealing with entirely fresh words and music.’ In this year, too the 22nd December she also performed among many others, including Cissie Loftus, (who had attended the same convent school in Blackpool) at the Coliseum for funding by the grand Order of Water Rats, in aid of William Treloar’s Crippled Children’s Hamper Fund.

In 1911 she is an ‘eccentric comedienne, whose songs may sometimes be coster and sometimes coon.’ The fact that she is described as eccentric would be a positive opinion of her uniqueness.

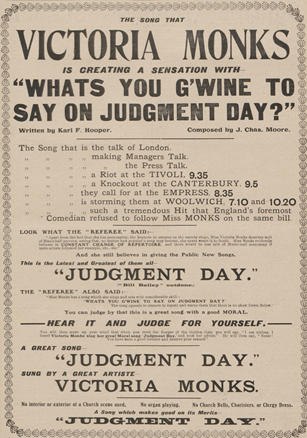

Her confidence and commanding presence on the stage in keeping the audience to attention is once more offered in the review of the same newspaper, The Umpire, column in 24th July 1910. In this she is compared to the preacher in her song, ‘Judgement Day’, in which the ‘dusky’ preacher of the deep south, in the singer’s imitative accent, warns his flock, or frightens them to death, as any militant preacher of any religion and in any accent would do, as much she does to her audience. … ‘I guess Miss Monks knows something of her powers. You can tell that by watching her on the stage. Statuesque, calm, self-possessed, and deliberate she always seems to be “keeping herself well in hand”.’ For the rendition of this song in particular, which rises to a crescendo at the end, a strong voice was needed and ‘Miss Monks’ indeed possessed such a capability of ‘a voice of double forte capacity.’ It was perhaps an attitude borrowed from the preacher she is imitating rather than being a blatant ridicule of his type, for the morality of sinning expressed in the song is the same for all human beings, which the audience in front of her constitutes. In her own self-possessing character, through the voice of the preacher, she might be dictating to, rather than merely entertaining. In referring to her ‘clarion tones’, which may be a result of her upbringing in the ‘boisterous breezes of Blackpool,’ … ‘she can sing in a key that is quite as convincing as that of the railway porter who yells, “All tickets please!”’. In her formative years, Victoria had lived next to the exceptionally busy Central railway line in Blackpool, but this reference was perhaps purely coincidental.

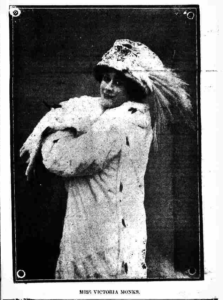

The Umpire 24th July 1910. Dressed in one of her trademark ‘frocks’ and a reference to her song ‘Moving Day’ which also required a strong and confident voice with clearly delivered lines.

Back with the Music Hall review of 1910, Victoria could indulge in what is probably nearly every young girl’s fantasy and that is to possess and dress up in wonderful clothes. One dress of Irish lace was insured for £130 (£12,670.64) and she had others and, to take up the words of the review, ‘On her pretty dimpled neck, she nightly wears diamonds to the value of £2,000 (£194,932.92). She was the originator of the little coat worn over the short gown, and she is about to startle the variety world in three months by introducing an entirely new style of dress. Some of her latest frocks are very smart. Handsome is a gown with colourings suggested by a flame, shaded to the faintest shade of yellow with a pink tinge, carried out in sequins and diamonds. A silver sequin coat over white glacé is worn with this fascinating gown. Another gown of silver shot satin has a helio lattice work over it in sequins. Shoes and stockings of helio accompany the frock. A silver-grey satin has a trellis work of cerise. A dainty coat of crepe-de-chine, with cerise sequin sleeves and silver shoes and stockings are worn with this charming toilette.’

And the same correspondent, ‘Marjorie’, delights herself once more in the same publication on August 11th, of the same year, ‘As a special favour to MUSIC HALL readers, I have the pleasure of describing several gowns that are in preparation for her. A lovely frock of royal blue satin is being made quite tight fitting and covered with a trellis work of pink and blue cup spangles. The underskirts are masses of foamy shaded salmon pink chiffon. Crepe de chine, that exquisite fabric so favoured by artistic costumiers, is the material of a beautiful gown just designed for Miss Monks. The whole of the tunic, which comes well over the hips, is composed of exquisite pearl embroideries. The fishwife drapery of crepe de chine is caught here and there with white silk tassels. A new matinee gown of powdered blue satin has the corsage of white lace embroidered with gold. The sleeves of rucked chiffon are held together by tiny gold and pearl buttons. A distinctive feature of the frock is a handsome pearl ornament which forms the lower part of the corsage.’ Perhaps an understanding of dress sense and couture, as well as little vocabulary, would help the imagination in reconstructing the dresses.

The same Marjorie is quite content to bestow praise upon the character of Victoria and if we were to believe her words, the Muscal Hall artiste is a very aimable character, keen to watch and enjoy and applaud other acts with genuine enthusiasm. She is not locked up in herself but will partake in conversation with interest and delight in any subject, ‘She laughs and applauds the good points like a jolly schoolgirl and is quick to appreciate the talent in others. Victoria Monks has a wonderful smile. It s not the perpetual “tooth grin” of the picture postcard beauties. It is a natural smile and illuminates her whole face.’ At the time Victoria was doing five acts a night at various venues in London but through this testing time of hard work she does not let the strain get to her and she is always, ‘bright and cheerful, alert and full of interest in the world round her.’

In March 1905, she was given a heavily feted send off at the Canterbury in South London, where she was a firm favourite and where she is billed as a ‘serio-comic’ before she was due to leave for America. The stage was bedecked with flowers around which she sang and danced her Afro-American parody routines in her ‘eccentric dance’. A floral procession of several baskets of flowers were brought on to the stage, prompting her to give a farewell speech at the end of her performance. Several ‘flashlight’ photographs were taken. ‘On Monday she appeared in black satin, with very stiff underskirts of flame-coloured chiffon and silk, a smart black coat with a bold design of flowers and scroll work round the sides, and an enormous hat, with beautiful shaded plumes 36 in long. Next week she is going to wear a frock as dainty as a piece of Dresden china. It fades from deepest rose into palest pink, and it is covered with cream-coloured lace that took first prize at the last Paris Exhibition.’ Such was her popularity that her bookings reach as far forward as 1912 it is claimed.

Andrew Thomas Monks, Victoria’s father.

It might seem evident that some aspects of the character of a somewhat, at times, self-assertive Victoria Monks might be understood from her father’s heritage. While her mother in her own right was not averse to standing up for her own sense of protection and justice with a boxer’s physical swipe at a male neighbour who vexed her, Victoria’s father had spent a brief time in the Bridewell prison in Liverpool. While this would normally suggest a criminal element in Andrew Monks, and there are several more instances where he is up before the County courts of both Blackpool and Kirkham, the nature of the incidents might suggest rather more of a character failing or inadequacy, which could occasionally manifest itself, at one time perhaps in extreme form and for which a modern psychoanalyst might be able to provide a definition. In all, he appears potentially as a likeable man with a focussed talent. Of his children, most of who are restless, energetic and expressively self-righteous on occasion, Victoria was perhaps the most evident example of this characteristic.

Andrew was born in Leeds in 1847 and married Mary Dalrymple in 1867. There is one record seen of a marriage between the two names and this in Stepney, London. Mary was born in Newcastle on Tyne and there is a little indication discovered as to why they would marry in London. They have children born in Manchester, Birmingham, Liverpool and, finally, Blackpool, so it is an itinerant and unsettled family at the beginning, as probably were the two individuals who met and created the family.

On the 13th April 1871 Andrew Monks was admitted to the Workhouse asylum in Liverpool. Classed as a pauper. He arrived it appears, from the ‘industrial school’ having contracted smallpox and remaining there until discharged on 2nd June, presumably cured. This would be the same Andrew Monks, aged 26 years, married and occupation of optician, who was returned to the same Workhouse from the main Bridewell prison on May 23rd 1873 and classed as a prisoner. In both cases he was discharged from the asylum and since no illness was described in the second instance, when he had requested his own admittance, it might be assumed another reason, even if a ruse, to get away from the prison confines for a short time. Regarding this confinement to the Bridewell, there is the report of an Andrew Monks back before the police court on June 6th of the same year having been on remand in the Bridewell for an offence committed on May 22nd. In the short column within the Liverpool Weekly Mercury headed ‘Freak of a Lunatic’ he had been arrested for impersonating a police officer after arresting a young woman he had grabbed in the street. He had taken her into a druggist store, rather unusually claiming she had something hidden in her hair. The young woman, a shop assistant, must have been terrified, but it appears that, curious and dramatic as the incident was, and especially traumatic for the victim, there was no self-satisfying criminal intent in his actions and he was classed as insane and, already having had treatment at the Workhouse and discharged from there by the doctor, he was bound over to keep the peace for six months. A modern interpretation of the event might, perhaps, be different and could offer more insight.

On the 1881 census return the family is living in Birmingham where they had relatives living with them, an aunty and uncle, Margaret and John, siblings to Andrew’s mother it would seem, and who were working in the shoe making trade. Victoria (Annie) is not yet born. John, (Jack when on the stage) who is Andrew and Mary’s eldest son, is nine years old and born in Liverpool as are daughters Elisabeth and Margaret. A son, Robert, is born in Birmingham and Andrew in Manchester. So there wasn’t much time for grass to grow beneath their feet nor the ability nor opportunity to settle in mind and spirit. The father’s opportunity to eventually settle down in life may have come about when he was able to fully pursue the occupation of optician in his own right for which there must have been an input of both favourable opportunity and cash at some point.

Soon after the 1881 census for some reason, the family move up to Blackpool, perhaps because it was a rapidly developing seaside resort where that opportunity beckoned. Annie was born in the town in the district of Revoe, though she was for some reason taken back to Liverpool to be baptised at St Peter’s Church, a church which would have its claim to fame in the music world, if the same St Peter’s where John met Paul for the first time and gave birth to the Beatles. The family, it seems, is in a position to stand firm and hold its own in the conventional manner of the district of Revoe, a district where both physical and material survival was by hard work or guile, not by the influence and privilege of material wealth as in other areas of the rapidly expanding town. Here, both Mr and Mrs Monks are quick to defend their eldest child, John, with violence and threat against the violence directed at him by their next door neighbour. Only a couple of years later the family is living in Duke Street, a cul de sac which backed onto the busy central railway with its hundreds of excursion trains a day, and Andrew has a qualifying electoral address of both 2 and 20 Duke Street. It is here at No 20 that his wife Mary dies at the young age of 36 years in 1884. Annie would be less than two years old and consequently would have grown up without a mother. It seems by now that Andrew might be a little more emotionally settled, but if a kind of paranoia had dogged him to date, events would show that it hadn’t entirely left him, and his daughters would it seem, take a little slice of it for themselves into their own lives. Moving from this address to that of the easterly expanding Blackpool, he settles at 24 Elisabeth Street, most probably as the first occupant of what is most likely a new build property. An electoral roll shows Andrew Thomas Monks as occupying 42a Milburn Street nearby in 1898 (which could be father or son, probably son) and 24 Elisabeth Street in 1900.

Within the personality of Andrew Monks, there are a couple of reported instances where, in somewhat delicate, perhaps precipitously hyper-sensitive state, he was prepared to take off his coat in readiness for a fight to justify his actions or merely threaten to ‘blow out their brains’ of the person confronting him. Once in Blackpool, and settled in Revoe, one of the two ‘working class’ districts of the town in which you had to roll up your sleeves to survive, sometimes with questionable legitimacy, Andrew found himself equal to it. So when, in the June of 1883 with little eight month old Annie Monks probably snug in her cot or equivalent, the next door neighbour George Aulder complained about Andrew’s 11 year old son, John, making a noise by his back door and he went out and allegedly kicked him, a vicious attack to which Mary Monks took exception and, subject to the fury of a mother defending her child, gave Mr Aulder a ‘backhander’ for which the neighbour retaliated and ‘threw her down’. This brought Andrew into the fray either at the same time or sometime later in the day and, with his own rigid sense of justice to protect his family and his wife, and usually the traditional male preserve of the day, though the woman could also be equal to it in the district as Mary had demonstrated. Described in some misplaced wording in the consequent reporting of the court case in the newspaper, Andrew took a hammer to George Aulder and, in a case of mixed metaphor, threatened to blow his brains out. The court dismissed the case as the accusations of both plaintiff and defendant conflicted beyond what could be judged as right or wrong and no reasonable judgement could be arrived at. Annie being so young, this particular event would have had no influence on her own similar propensity to impassioned self-justification led by the fist into the ranks of the perceived enemy. But it wasn’t the only time her father was on the defensive before the courts, and his personality and its consequences may have had an influence in teaching her that characteristic. Among the total chaos of life around her, life indeed would appear as that literary ‘stage’ and for the family it might as well ‘strut and fret’ upon this stage as it did turn out for four of them. Andrew senior himself played his part too, as there is indication that he acted as a theatrical agent, and if so, perhaps beginning with his children in the early days of their careers.

When Annie’s mother died in 1884 while the family was resident at 20 Duke Street in Blackpool, the children’s influence thus was from their father alone. If the children might well have been unaware and not informed of their father’s prison past in Liverpool as they would have been too young to be aware of it at the time, in the November of 1888 Annie would be aware, for the first time perhaps, of her father’s attraction to controversy as he was in the County Court accused of swapping a pair of opera glasses in his possession for an inferior pair which he had allegedly returned to the rightful owner. It didn’t help his case much when the rightful owner was a Manchester Police Constable who was reclaiming his £2 (£205.64) opera glasses for the ones he had been given instead, and valued at only 10s 6d, (approx. £51.44) just over a quarter of their true value. As the story unfolds the policeman, John Gordon, had left his opera glasses at a house in Blackpool in which he had stayed during a short break in Blackpool. It seems that he may have originally bought these off Andrew, for he had reason to write to him and ask him to call at the house in which he had stayed and retrieve the glasses. The claim was that Andrew had accepted his request and collected the glasses but had sent him an inferior pair in their place, for which John Gordon came to Blackpool to confront him resulting in him claiming that Andrew, in the face off, had taken off his coat ready for a fight. Andrew then counter claimed that it was John Gordon who had assaulted him and so he had immediately gone over to Manchester to complain to the Chief Constable there. In front of the county court in Blackpool, Andrew had agreed that the glasses that John Gordon had received were the ones that he had sent, but they were also the ones he had received off Mrs Clay, the landlady. At this point the case could not be decided with any certainty for either party and there was no evidence that either Mrs Clay or her friend Mrs Slater, who was present at the time Andrew called for the glasses, had swapped the glasses in their own interests. The conclusion of the court was that since Andrew Monks had the responsibility for the glasses which he had agreed to retrieve, then, if there was any blame to be apportioned, it would have to be to him, and he was fined £2 as well as the costs for the two witnesses present.

The somewhat nervously self-preserving nature of Andrew emerges again in 1895 over the misplacement of a wedding ring. It would seem now that he had been working successfully as an optician and owned property but, in this year, he was back in the County Court in Blackpool accused of not returning a wedding ring to its rightful owner. A Mrs Nancy Westhead, wife of a cab driver in the town had pawned a wedding ring but when she came to redeem it, Andrew Monks, whose address is given as Lytham Street, (now Corporation Street) his business address, was there with a policeman claiming that the ring had been stolen. It had belonged to his sister who had shared his house address until she had died last year. While Mrs Westhead could not be accused of having stolen it, having bought it off a travelling salesman after her own wedding ring had become worn, meanwhile Andrew claimed it was the ring he had had made to special order, which was in conflict with evidence anyway. Whoever was right, the decision went in favour of Mrs Westhead as a case of the confusion of mistaken identity of the ring, and Andrew was ordered to pay £4 (£435.20) as compensation or 50s (£58.40) if the ring was returned. Another report gives £3 and 10s as the stipulation, both costs being much less than the £20 (£2,176.00) claimed by Mrs Westhead. Annie, the youngest in the family would be only thirteen years old at the time and sensitive enough of age to develop that sense of precipitate self-righteousness, and grievance at the accusation of being wrong even if she knew she was wrong, with a mix of doubt and confidence that would punctuate her own life and career.

And then again in 1903, after Victoria was pursuing her successful career away from the family home, Andrew Monks of 24 Elisabeth Street was in front of the Kirkham petty Sessions charged with three counts of defrauding the railway company of tickets between Liverpool, Preston and Wigan on three different dates, and also with using a second class compartment with a third class ticket on another date. He was found guilty and fined 30s (£150.30) and costs. One trip was to Haydock races so perhaps he liked a flutter or was just there for a day out with friends. His defence seems to always echo with the naive simplicity of not being over aware of doing anything wrong, or perhaps he knew he was wrong but was unable to admit it even to himself, or the air of feeling his actions were right and just without the need to query them… and maybe there was a little bit of getting away with what you can which is often a natural element of the human condition. The distance in time away from these events is too great to make a definitive claim of the amount of innocence or guilt.

Andrew’s eventual respected status and achievement is notably expressed at the annual Arts and Industries Exhibition for Blackpool and North West Lancashire, held at the Winter Gardens in Blackpool for at least two years in the June of 1890 and 1891.

And his daughter Elisabeth, not be outdone, was claiming justice, for items she had sent to the cleaners. In the October of 1901 she claimed £4 13s 6d (a little less than £500) from Crawshaw and Co, dyers and cleaners. Items included coats and a feather boa. The feather boa had not been returned and the judge, it is intimated, did not regard the complaint as very serious. Perhaps, being a male he only understood that the clothes, and the quite luxury items as they were, as unnecessary paraphernalia for fussy women, even though in the male mindset women were expected to look good for male visual consumption. It is not stated but again, intimated that the boa was returned, though uncleaned as the Company claimed it wouldn’t clean properly. There was enough in the complaint however to be awarded 40s (£203.41) compensation.

Alfred’s own last memories of Blackpool would be when, in evidently good health, he had left Blackpool to visit Victoria in Norwich where she was playing. Peggy was also down in London performing and staying at Victoria Lodge 104 Tulse Hill, Victoria’s residence which her sister had only recently acquired some weeks ago. The gardens to the property were extensive and included an orchard and Peggy persuaded her father and sister to visit her. They travelled overnight by car arriving at 4am and the three spent an enjoyable day together with the dogs and took many a photo and enjoyed a good dinner in the early evening. In the evening, however, as they sat together, Alfred suddenly fell forward from his chair and was found to be dead. The picture of the two sisters, father and the dogs had been taken on that day, the last day of Alfred’s life. Victoria and Peggy cancelled their engagements and Victoria was later due to play in the Midlands. Peggy came back to Blackpool while Victoria stayed in London to look after the funeral arrangements. The body was brought back to Blackpool and interred in the family grave at Layton cemetery.

The funeral took place at Blackpool’s Layton cemetery on Friday 26th May, the body having been brought back the day before. It was intended to be a quiet affair with only family members and a few friends invited. However, a large public presence was reported at the cemetery. The officiating clergyman was Rev Job Edwards of Christchurch. Among the many floral tributes was an ‘artificially worked cushion’ and another representing the Gates of Heaven.

Style

Features of her act, and which belonged to the Music Halls in general, were her coster and coon songs, both in the innocence of ignorance or the ignorance of innocence. The low, perceived, social standing of both the working class ‘coster,’ and the Afro-American, was easy meat to patronise, criticise or ridicule or perhaps unconsciously imitate in flattery. As early as 1898 Little Victoria Monks, aged 15yrs is listed as a ‘serio-comic’ at the Empire in Wigan. Also billed on the same night is a ‘negro’ comedian, which might have had a further influence on her later acts. She had perfected a ‘coon’ song and dance, for which she earned ‘an ‘irresistible cheer’ while still a teenager, at the Empire Music Hall Burnley, in March 1902. Of this genre, ‘Won’t You Come Home Bill Bailey’ was a song imported from the USA which she made famous, and equally which made her famous too. Or she could sing, dance and act in accompaniment or with a lavish stage set around her, and sometimes she would use a stooge to play off.

Later on she turned to poke fun at the rag time glide (the ‘Vicky Glide’) which was a mad craze sweeping the dance floors in 1913 and in her sketch the ‘Extra Turn’ in 1917 revitalised her career for a short time. She could sing on her own, and her voice was in loud form so much so that the manager of the Hippodrome in Preston, suggested he should reinforce the rafters of the building, and so popular was she in this town that he would be willing to remove the wallpaper from the walls in order to get more people inside.

In 1904 she had already been on a successful five week tour at Johannesburg Empire, South Africa and, on her return to the Palace theatre London for the Easter programme, a six weeks stint, she had been called ‘Saucy’ Victoria, aged 21 only. The announcement in the Era of September 1904 of her marriage to Karl Hooper (birth name, Karl Gruhler, an American) in August of that year describes her as a ‘charming burlesque actress’. From that date it seems that her husband became her manger as he ran his own theatrical agency

She was often confused for an American, perhaps because she had married an American, but she was always patriotically British whatever country she might be in. In 1919, in a misconception of Victoria’s nationality on both sides of the Atlantic, it was reported in the Leeds Mercury of May of that year that, after a dinner given in America in her honour for an exceptionally successful tour there, she was toasted as ‘one of our compatriots’, to which she immediately retorted (Victoria was usually not one to keep her mouth shut), ‘I am not. I am John Bull’s girl’, a title of one of her popular songs. In an incident while she was on tour in South Africa and during a train journey and no doubt travelling first class, she had sat next to Christiaan De Wet, the Boer War General. She had shared a glass of wine with him, but then he mistook her for an American and naturally and openly he began to berate the British. On this occasion, no reaction was recorded from Victoria, and ‘John Bull’s girl’ as she was known might have only kept herself quiet as the bottle of wine might not have been finished.

By November 1906 Victoria was earning large sums. Since March she had earned £1,500 (£150,915.81) in musical hall salaries and she had a recording contract (‘to sing songs into a gramophone’) worth £360 (£36,219.79) a year. ‘This week she would earn £80 (£8,048.84) for two engagements of £40 each’. These figures were declared in court when she and her husband were defendants in a case in which they had been accused by Harry Jacobs, manager of Wonderland in Whitechapel of lending them money (£35 and £30 respectively; £3,521.37 and £3,018.32) which they had not returned. In the course of the proceedings it was intimated that Karl Hooper was in the habit of striking his wife. Though this was never substantiated, it was perhaps an indication perhaps of the volatile and unsettled life that was Victoria’s inevitable lot. Both claims were dismissed with members in the public gallery of the court vocalising their disbelief.

Earning this kind of money brought in the crooks and while Victoria was performing at the Duchess Theatre in London there was a cheeky attempt to obtain her salary while she was away from the building in between shows. There had been a telephone call to the manager, Mr Bertram Ross, claiming to be her husband Karl Hooper, stating that Miss Monks’ had had an accident in her carriage and she had sprained her ankle and couldn’t perform. She would need her salary and consequently someone would be calling at the theatre to collect it. That person did arrive at the theatre but Mr Ross was equal to it and said that Victoria could collect the salary on Monday morning and the messenger went away with nothing. When Victoria and her husband Karl Hooper arrived for the second show, they were surprised to learn of the plot.

In March 1918 two of her Pekinese dogs and about £90’s (£4,231.71) worth of property were stolen from her flat in Hart Street. In 1920 her address is given as New Street, St Martin’s Lane in a report where thieves broke into the flat and stole clothing worth around £100 (£3,698.33) which included a brown fur coat, a musquash and sable coat, three stockingette dresses, a blue and gold embroidered dressing gown and a silk dressing gown. The thieves had got in by removing the fanlight from the front door.

By January 1907, Victoria had sneaked in a little more sponsorship as she praised the propriety coughs and colds cure known as ‘Peps’ in a newspaper advert. What does come across is her lasting trouble with bronchitis and ‘throat lag’ which she was prone to after singing. She recommended Peps to all, especially singers.

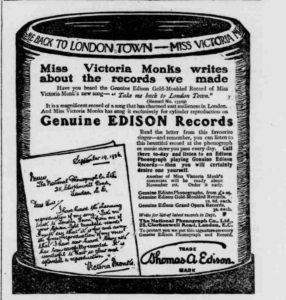

Eventually, as technology was setting out on the path to change Music Hall for ever, the songs of artists were played at intervals in performances, as at the Aberdeen Empire on George Street in March 1908 when her songs and those of Harry Lauder were played on a ‘pathephone’ (gramophone). The disembodied voices of the singers could now be heard on the stage, or at home without needing the real person to be present in the flesh.

In May of 1908 Victoria was in the general news for good reason. In the aid of the Music Hall Ladies Guild which raised funds for female artistes and their families who had fallen on bad times she, and a ‘bevy of vivacious damsels’ invaded a crowded Throgmorton Street in London. She arrived in a car and was soon joined by Ella Retford, Maude Mortimer and the president Mrs F Ginnet. Victoria Monks was described as wearing a ravishing white bebee hat and a rich, mauve tinted cloak over a white dress’. They went down the street disturbing the usually seriously business of broking as they were audaciously selling tickets for a matinee at the Oxford Theatre in aid of funds for the Guild. It is assumed that the escapade was successful and the brokers took some delight in the surprise interlude and might have been persuaded to buy a ticket, through the charm of the ladies, even though they might have had no intention of going. The party certainly succeeded in attracting a great deal of attention, but the only negative aspect in the all-male preserve of the ‘sacred’ Throgmorton Street was that on occasion, despite the goodness of their enterprise, the women were mistaken for the much maligned suffragettes.

In October 1908 at the Empire in Bristol Victoria’s varied talents were praised and she ‘is in the top flight of comediennes’. The song entitled ‘Moving Day’ was of the ‘coon’ variety.

In 1909, on stage at the Canterbury Music hall, she was the only performer who was able to get a hearing, and any sense out of a number of rioting, medical students, who were shouting and hollering and throwing fruit onto the stage at several of the performances, since the act they were expecting, Dr Bodie, the bloodless surgeon, was not able to appear because of illness. The safety curtain had eventually to be let down and the performances suspended, but Victoria took it upon herself to lead one of the more reasoning students on to the stage by the hand (a delight to him, no doubt) and some sense of order was achieved before the police arrived. Victoria was certainly self-motivated and at the height of her popularity also must have held quite an amount of influence.

It was in this year of 1909 that Victoria took up roller skating. The leisure activity had become a craze and roller skating venues popped up everywhere and professional roller hockey was played at these venues too. There is a photograph Victoria and Marie Lloyd together in the Era of the 4th December 1909 in which they are shown before their ‘Double Rinking Act’. Unfortunately for this account, it is too dark to reproduce, as often photographs haven’t digitised very well. The activity of roller skating had been made popular for the stars by Marie Lloyd at the Earls Court rink and Victoria had taken a liking to it, claiming it was ‘simply lovely’ and wished she had taken it up a year earlier. Mostly, as an activity, the roller skater just went round and round the rink but there were more complex manoeuvres that could be undertaken and these ‘figures’, as in ice-skating, could earn points in the professional competitions of figure roller skating. It is not recorded how much either Marie Lloyd or Victoria Monks were proficient in anything beyond merely the leisurely pursuit of the activity.

1912 was the year of the first Royal Command Performance to celebrate the coronation of the new King, George V. Victoria was on the stage, along with 142 others, among who were Cissie Loftus who had a brief spell in Blackpool during her education, and Walter Munro who would come to the town for health reasons and stayed, and is buried in the same Layton cemetery as Victoria’s family. And there was Vesta Tilley who would get to like Blackpool and even convinced her impresario husband Walter de Frece to successfully campaign to become MP for the town.

In this year of 1912 her status as a ‘feminine coon’ singer is renowned and the audience at the Palace theatre in Hull would be hard pressed not to believe ‘that she wasn’t one herself’. She had just returned from a sell-out tour of America. However, it seemed that America hadn’t enthralled her entirely. In a reference to her time there, the Sporting Chronicle of 1916, in a gossip column with information acquired from a recent conversation with Victoria, described her retort to an American society woman who, ‘didn’t think very much of your Queen Alexandra.’ Such was Victoria’s popular reputation and the evident understanding in the view of the columnist that he feared for the American woman. Emphasising her Britishness as ‘John Bull’s Girl’ and her characteristic indignation bursting to the surface, she told them just who Queen Alexandra was and just who the woman front of her was. That American society woman, the columnist emphasised, would have certainly learned in clear terms something that she didn’t know, perhaps even in words she hadn’t heard before and, no doubt, would have been left with a bee in her bonnet. As John Bull’s Girl she was steadfastly British and was not so keen on America. The heritage of her roots in her homeland seems also to have stuck with her in her consciousness, if not in the exercise of her wealthy lifestyle and absorbing the adulation resulting from her fame. In contrast to this lifestyle, as reported in 1916, she was a big fan of Ben Tillet the Labour leader and no doubt this stemmed from the experience of her upbringing especially with the females, as the right of value and expression of the individual whoever they were. If someone can’t be heard or valued they should fight for the value they see in themselves in order to be accepted. It was a time too, when the suffragettes were not letting go of their objective, though there is no evidence for this account of Victoria being involved physically in the group’s activities.

In March 1914 Victoria is embroiled once more in the interactive nature of the Music Halls and she and showed her sympathies with the ‘working class’ idea. The film show of the 1913 Johannesburg labour troubles in the gold mining communities on the Rand, emphasised by the violence of workers versus owners and government, and resulting in the ‘massacre’ of Johannesburg market Square and the burning of the railway station, was shown at the Palladium as part of the show. Maybe Victoria was aware of the presence of a whole group of trade unionists in the galleries, or maybe her references to the nine deported labour leaders from South Africa were merely topical coincidences, but her show caused a noisy reaction in the galleries. Her act was delivered in repartee with her ‘burnt-corked’ stooge, a character of lesser given status than the white trades unions whose jobs were in danger of being usurped by the indigenous, black population. The galleries erupted, claiming that Britain was just as oppressive, as the more expensive stalls below looked up above themselves in alarm.

The massacre of the market square, Johannesburg in 1913, had involved about ten thousand strikers and families. It was mostly a white crowd, the black workers who numbered about 200,000, had been forced violently into the mines with threats of severe sanctions and few, no doubt, could risk overt action. The crowd, already in a nervous mood, was attacked by the police and a handful of dragoons. As the situation deteriorated, guns were fired indiscriminately killing 21 and injuring 47 men, women and children.

Though it was the beginnings of a working class movement, it was only a white working class, and these were mostly from Britain, (many of these -50% has been quoted – were Cornish and they sent their money home to their needful families). Victoria’s brother Jack himself is reported to have worked in the lucrative South African mines. Racial segregation was proposed in the region as well as the enforced repatriation of Asian workers. In this light it can be understood why Victoria could use her evident skill at getting the crowd on her side. Her reference in repartee with a ‘burnt-corked’ individual to the number 9, (the number of trades union leaders forcibly deported from South Africa), provoked the galleries into a delight of both self-righteousness and of condemnation of the perceived aggressors, but the ‘burnt-corked’ individual would, with as much injustice, have to wait decades for a concept of equality while continuing to be the butt of jokes on the stage, and of discrimination and violence off it.

In June 1914, and now some time after her divorce, and some further time after she had ceased to live with her husband, Victoria’s style and stage routine is noticeably different. At the Nottingham Empire her act is recorded as losing a little of the verve of her previous routine, though nevertheless successful. In her number, ‘All Aboard for England’ the stage is dressed like the scene from a play, with wind effects and a landing stage and the ‘sighing’ of the sea, as the comparisons of England and America are aired. It also included a ‘burnt-corked’ individual in a comedy scene which once more reprised the delight of both white-skinned home and Transatlantic audiences with the curiosity of the ‘negro’, the Afro-American. Miss Monks had an aptitude for the curiously named, ‘coon shouting’ which was ‘quite Atlantic’ and which, in ignorance, such interpretation was not able to understand the injustice it was no doubt expressing.

In stark contrast to this, in October 1914, the ‘white’ crowds of Marseille were enraptured by the arrival of the Indian army. It took several hours for the Sikhs and Ghurkas to disembark from the troop ships en route to the theatres of war in northern Europe. They were showered with tricolour flags and flowers, and there were those who even took it upon themselves to shake their ‘brown hands’. Three years later, the Afro-American buffalo soldiers, formerly ‘stolen from Africa’ as the song goes, would disembark in France, to a similar reception along with their white compatriots. They would be fighting for a concept of freedom which belongs to all human beings.

In 1915 Annie was singing patriotic songs written for her. In January she was at the Empire, Sheffield and in May at the Holborn Empire, singing new songs, one particularly patriotic one about her opinion of the Kaiser. At the Leeds Empire in April 1915, shortly after, Neuve-Chapelle, the first real trench-to-trench battle of the War, when the fighting had been notched up a degree, and when men on both sides were being slaughtered in their thousands, a critic in the Yorkshire Post, intimated that it was inappropriate for Miss Monks to use the word ‘damned’ (printed, ‘d….d’ in the newspaper) when referring to the Kaiser as a ‘damned old fool’. Slaughter, as patriotic, it would seem, could be justified but ironically, it might seem, swearing in public could not. By 1913, George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion had been performed, and there was controversy over the word ‘bloody’. While Victoria was happy in using the word ‘damned’, she was less keen on being obliged to use the word ‘bloody’. The point being that a word from a play that an actress or actor was expected to repeat – would it be unprofessional not to? Victoria claimed she would not take her 14yr old niece to a play in which there might be unsavoury language. Swearing should be used in the appropriate way at the appropriate moment maybe, but not as free range of expression anytime, anywhere it might seem to her.

Victoria’s career moved on, but not perhaps with popularity of her former years. She was still a respected artiste and a crowd puller but the nature of entertainment was changing. Songs, like alcoholic drinks today could be bought and taken home to be consumed and films, which brought a different kind and excitingly new diversion to reality, were being shown at theatres. But in 1917 in Leeds she can still pull in the crowds. In a sketch called, ‘The Extra Turn’, she displays her vaudeville skills to the appreciation of the audiences. Victoria’s engagements continued regularly, and in 1924 she has a new song described in the Era and entitled ‘Waitin’ Around’, an American foxtrot song. Victoria feels it is the best song since ‘Bill Bailey’, the one that had made her famous. In August 1926 Victoria was performing three shows a day (one matinee and two evenings) at the St George’s Cinema Bexhill-on-Sea. After her performance there were film shows which indicates the demise of the old style Music Hall. She was innocently referred to as a figure from the past, her songs were ‘in vogue twenty years ago’ but she nevertheless still commanded a great popularity.

By 1909 Victoria Monks, mark 2, Victoria’s niece via her bother Andrew’s marriage, was treading the boards, Victoria being her birth name. It was the annual children’s fancy dress ball held in the Empress Ballroom of the Winter Gardens. Victoria was ‘Joan of Arc, leading the battle.’ The annual ball was always a grand affair with lavish costumes and accompanying orchestral music and dancing and the balconies were filled with families and friends. In the newspaper description by regular correspondent ‘Dorothy’ who delighted in the exuberance of describing such events, ‘Little Victoria Monks was most decidedly ORIGINAL AND VERY DELIGHTFUL in her historic costume of Joan of Arc, the famous French heroine. The pretty little thing wore a complete suit of armour composed of innumerable circular rows of silver spangles of about the size of a sixpence. Right from head to foot she was covered with the shimmering glistening coat of mail, her tiny legs being encased in leggings of the same “armour” but it was easy to see that the little thing could move quite easily in it. She carried her white, plume helmet with an air, I can assure you, while round her neck were pendant beautiful rows of large pearls.’ In 1911 Victoria is once more at the children’s fancy dress at the same venue, this time appearing as Boadicea. ‘Dorothy’ of the Blackpool Gazette and Herald once more went to town with unbridled enthusiasm on the costumes. Immediately behind a little girl, Mollie Selkirk, dressed as ‘the perfect embodiment Summer’, ‘walked a bonny little, Victoria Monks, as “Boadicea”. Her costume was composed of silver armour, exactly as we have seen the famous Queen in pictures. The little girl also wore a silver helmet, plumed with brown ostrich feathers, and carried a spear and shield in captivating way. She also wore brown sandals. Indeed, her costume was absolutely perfect. With her was Karl Victor Hooper, a handsome lad, who came as the “Diamond King,” and very faithfully he carried out the character. He was aglitter with silver, studded with “diamonds” which shone beautifully among the silvered cloth and material of his costume. A long, fringed tie, like a Jabot, was blazing with diamonds which also bordered his lovely silver coat. His boots were studded all over with brilliant diamonds, as was his jaunty cap. He also carried a diamond studded stick, and wore diamond Marquise rings.’ There did seem to be a promotion of the female in the themes adopted by little Victoria, perhaps inspired by the success of her aunty. And for Dorothy, to not only describe the event but to meticulously describe all the children, she must have had a well of ink even if working in shorthand. Karl Victor Hooper was Victoria’s son who spent some time at 24 Elisabeth Street while his mother was away on tour and his education was conducted at St John’s school in the town centre.

Court Cases

Victoria’s life was studded with court cases. As early as November of 1899, billed as Nancy Victoria at the age of only 15 she was involved in litigation which would be a theme of her professional life and which would eventually ruin her financially. In November of that year at the Blackpool Empire she sang a controversial verse of a song which the manger had asked her not to sing. The song, ‘We don’t intend to have it any more’, was a little critical of the French and the manager at the time, Mr Lemee, happened to be French. But Victoria wanted her own way, which also would be her characteristic throughout her life, and she may have, even at that young age, cheekily and deliberately included the banned verse. As a consequence she was summarily dismissed from her two week contract. Her father, no doubt proud of his daughter and quite content to take her side, sued the Blackpool Empire Ltd for £12, (£1,275.92) though subsequently Victoria’s first legal case was lost. She had been engaged at £5 (£531.64) per week.

In June 1904 Victoria was involved in one more of her several court cases. She had alleged that Miss Mattie Oxberry, a member of the Knick Knacks (and who had songs and a routine quite similar to Victoria) had stolen some of her songs. When confronted after the show, there was a scuffle and Victoria received a cut lip and a black eye. The blow appears to have been invited, a ploy which Victoria might well have used in all her later altercations, though one witness claimed that Victoria had struck first with her handbag. The case was dismissed on the condition that Miss Oxberry would pay 5s (25p; £100.61) to the poor fund.

In November 1904, with Victoria now married to Karl Hooper and earning £60.00 (£6,036.63) a week, it left the other members of the family at home in Elizabeth St, the two sisters, Margaret and Elizabeth, and a brother, with their father. Both sisters at this time were also music hall artistes, though not currently engaged. The brother, too, would join Victoria in a show on at least one occasion. Margaret is described as ‘serio-comic’ and singing songs such as ‘Dreamy Eyes’, ‘Always Loving’ and ‘When Mr Shakespeare Comes to Town’. Bessie had not worked for some time. It seems that they had a dispute with their neighbour over the painting of some party railings in between the houses. The neighbour took exception to it and found a golden opportunity to call them some choice names and impugn their reputations which was easy to do since women were supposed to be pure creatures and keep themselves that way. In the Court case at Manchester Assizes that followed, the words alleged to have been uttered by the coal merchant next door, a Mr Livesey Howarth, were not pronounceable in the courtroom. The sisters wanted it emphasised that being music hall artistes did not mean that they were ‘loose’ women and they wanted their good repute to be made public. Margaret was awarded £5 (£503.05) damages but the case for Bessie was found against her and costs were awarded against both sisters. However, Bessie was back in court the following year for non payment of the £8 7s 3d (approx £844.00) awarded against her. Her non-ability to pay was exposed in court, the first case to come before the new circuit judge Hamilton at the Blackpool County Court. The financial status of the Monks family was questioned and it was revealed that Margaret was at home in Elisabeth Street, the address they shared with their father, looking after the household and hadn’t worked for over a year. Elisabeth, as Bessie, could earn from between £2 and £3 a week (£201.22 and £503.05). However, she wasn’t working at present and when she wasn’t working in her own right she would often act as dresser to her sister, which would imply Victoria. When the financial status of the father was queried she explained that he was a travelling optician and it was her brother who had an optical stall on the market not her father as the two shared the same name.

The case might have been an excuse for the prosecution to disguise the contempt for a female Music Hall artiste and intimate with impunity, in legal language, the lack of morality of such a person. Elisabeth perhaps didn’t help her case for an inability to pay as she presented herself before the judge in a ‘very elaborate hat of a pale blue shade, adorned with forget-me-not. The size was prodigious.’ In a rather patronising conclusion, ‘Even if you lived without that hat it would be something,’ the judge, considering that both sisters were talented women and could easily find work even if only sewing with their hands, he ordered that they should pay 5s (approx £25) a week. In all it had been a complex argument about costs drawn up by the solicitors and the judge of the original Manchester Court hearing. Mr Howarth, despite having paid out large amounts as he was required, had not received anything back and only wanted some of it back at least.

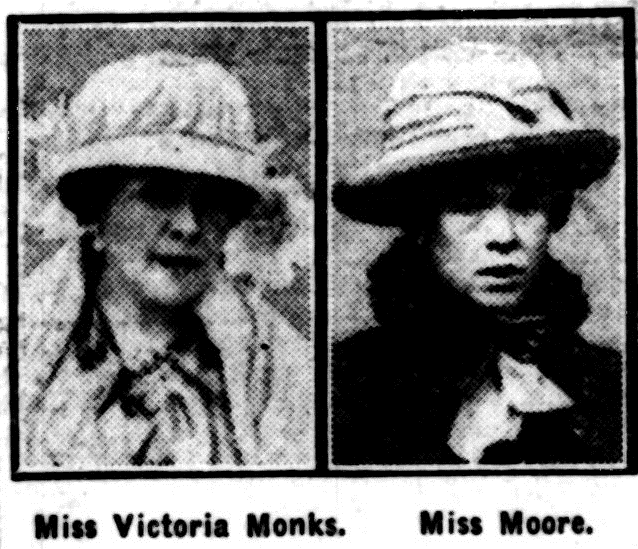

In May 1913, Victoria’s skirmishes with the courts resumed. Her personal life was faltering and the separation from her husband would soon turn into divorce. She lost her case against her former friend of twelve years, Theresa Russell, a musical hall artiste known as Florence Moore who claimed she had been slandered, assaulted. The complaint even contained one of trespass against Victoria, since Victoria, in the rage of her determination, had climbed in to her house through a window after being thrown out the door during an altercation. Florence claimed that she had been called a thief and had been given a black eye over a dispute with some furniture that Victoria had left in her care while she was on tour. The newspapers have many reports of the incident, some differing in detail and some enjoying a loaded content to make a more lurid story. However Victoria’s character does come through as that of expressing serious indignation at her actions being called into question, a family trait, seemingly inherited from her father, on being impugned by those who have no right, even in law, to judge. It gave the opportunity for the court to ridicule the women and the courtroom to have a laugh at their expense in disguised language as they were only women after all, and Music Hall artists at that, who were unbalanced and affected, unlike ordinary women who should now their restricted place in society.

The case proceeded like a one act play, as the story unfolds, in more than a hundred nationwide newspaper articles. There are the two women, a theatrical agent, a solicitor, a waiter, a builder and a chimney sweep all reported as being present at one time or another, and entering through doors or windows, stage left or right at opportune, unscripted times. The story begins in late 1912, when Victoria was about to move out of her house at 104 Tulse Road and was also going on tour at the time. She had asked her longstanding friend, Theresa Russell, to remove her furniture and effects to her friend’s apartment at 69 Hackford Road in Brixton and sell on what she could.It seems that when Victoria returned from tour, she called at her friend’s house where she had since moved to 18 St Annes Road and trouble that was already brewing, via a phone call from Stockton on Tees where she was performing, exploded. It seemed to be a delight for the court to talk about two women fighting when it was their considered place in society to be quiet, withdrawn and demure. After Victoria had called at the house and had been invited into the premises, she immediately took exception to some of her property, valued at around £800, (£76,381.88) being on display, as if it had taken into ownership by her friend, Theresa. A row broke out and Theresa asked Victoria to leave after she had accused her, in expletive language, unbefitting of women according to the court, of being a thief and she was going to get a van and collect all her possessions and take them back. She did return sometime later along with her manager Mr Wragg, whom she would also have a fight with the following year, and her solicitor Mr Kingsbury. While, it seems that Mr Kingsbury was allowed access to the house, both Victoria and her manager, having been denied that access, climbed in through a ground floor window, witnessed from an upstairs window by a builder who was working on the premises at the time and who didn’t raise the alarm because he had a mouthful of nails at that moment, and which caused one of the many giggles during the court session. Maybe it was the male builder’s convenient way of saying that he was going to enjoy the uncomfortable proceedings of society women in conflict.

The first accusation of a physical assault comes from Victoria who alleges that Theresa kicked her on the way out in the first place. Theresa was more than surprised to see Victoria in her drawing room and perhaps wasn’t prepared for the assault from Victoria which came next, the alleged blow to the face cutting Theresa’s lip and giving her a black eye. Not satisfied with that, Victoria took off her sealskin coat and was ready for more until prevented by the arrival of the two men at some point. The two women had had a stormy relationship to date as it was revealed by the court. Victoria had allegedly asked Theresa to leave her home in Tulse Hill because of her affection for alcohol and she was often drunk in the street and there had also been an incident in Preston, which was referred to, with a wry smile by the court which appeared having a great time, where the two had a row and Theresa allegedly hung onto the back of Victoria’s car as it was moving off and Victoria Monks had to have police protection from her.

The conclusion of the case between the two women saw Victoria having to pay £50 (£4,773.87) in compensation with costs, not a high amount for her current income.

In March 1914 she was sued by the Glasgow Empire for failing to perform on twelve occasions at the venue while under contract for £150 (£14,321.60) a week, a salary ‘considerably larger than that received by a Cabinet minister’. She was fined that £150. Though she claimed she had been ill, no medical certificate had been produced.

As officially Annie Victoria Gruhler she was in court again in November 1914, this time the plaintiff was her manager, Ernest Wragg, who also had his own act, and with whom she had had a stormy professional relationship. He was suing her for wrongful dismissal and loss of earnings as well as stealing a ring which belonged to his wife. Victoria was easily upset and was soon into a temper if an argument ensued. The alcohol that both consumed after the shows didn’t help both parties as both were partial to it. Violence was a natural part of Victoria’s arguments and this time, it was alleged by Ernest Wragg, that she had thrown a bottle of ‘lung tonic’ at him, broke things in the room and spat at him. In court, it was evident to the judge that Victoria Monks was a very emotional woman and, though nothing was categorically proven, he found the case for the plaintiff, Ernest Wragg, though the amount sought was reduced from £100 (£9,547.73) to £95 (£9,070.35) with costs. The fact that she already possessed plenty of rings and jewellery (and she held up her ring-laden fingers for the court to see), poured doubt upon the allegation of stealing the ring, which she hoped the court could accept as evidence.

Victoria’s court actions didn’t stop merely at her professional associates, but they also included family. In January 1915 her sister Margaret (Peggy Monks), who had an address on Aytoun Road, Stockwell, London at the time, brought an action for slander against her younger sister. A settlement was reached and Victoria voluntarily paid the costs. It seems that there had been a third party involved who may have been stirring things up, though it does reveal somewhat a strain and of a lack of trust between the two sisters. Victoria’s explanation was that she had left for South Africa at the time the action was taken and knew nothing of it till her return home. She denies ever having slandered her sister and would have no reason nor desire to do so. She would however, be prepared to pay costs.

Shortly after in the February of the following year of 1915, Victoria was back in court, being sued by Mr Edward Maxwell and his wife for ‘wrongful dismissal’ and recovery of unpaid wages as both her manager and housekeeper, respectively. The incident referred to the 15th September the previous year when, after a performance she, with a preference for crème de menthe and he, her stage manager in part, with a preference for beer, came home late one night to Miss Monks’ house at 104 Tulse Hill. Victoria must have been living at the house despite her divorce, and claimed that ‘her husband would not be at home when they got back’, not perhaps with a ‘come up and see me sometime’, inference but more that her husband might have objected and anyway Mrs Maxwell was at the house too, and she had opened the door to the two.

It turns out that the Maxwells, both Music Hall artists, were staying at the house and Mr Edgar Maxwell was employed for £2 (£170.12) a week and all expenses. Mrs Caroline Maxwell (whose stage name was Carrie Joy), opened the door and Mr Maxwell accused ‘Friday’ as the private hire chauffeur (real name Clyde Burchett – or referred to as Victor Nathaniel Lavender) who was now in the Armoured Division of the Royal Naval Air Service, of damaging his hat. Accounts differ, in one, Miss Monks took the side of her chauffeur and Mrs Maxwell that of her husband. It was claimed that Victoria had hit Mr Maxwell with a golf club. In typical fashion Victoria said that she didn’t have any golf clubs at the house and that she had never played golf, a claim that was countered by a witness who had said that he had played golf with her. But there was evidently an ugly, drunken scene in the front garden where Victoria had also allegedly picked up a rock and threatened to hit Mr Maxwell with it. The police were called and Maxwell was taken in charge while Victoria invited the policeman in to dinner where they had roast beef and a few drinks (somewhat sarcastically referred to in Court later on) and as much as these reports can be believed. The problem that the judgement of the courts had with most of Victoria’s cases that came before them was to decide who was telling the truth. In the drunken shambles of the event, many things were said and screamed out and many actions alleged, and all contained substance for the court to attempt to impartially determine and the newspapers to enthusiastically report in their own way.

During the trial, with the prosecution attempting to explore the irrational nature of Miss Monk’s behaviour, it was claimed that she had at one time ripped the clothes of her sister Bessie Monks to prevent her from performing, and had thrown a cruet set at her. Bessie Monks, Victoria’s elder sister was an occasional singer on stage with her sister. In the witness box Victoria wore a smart, navy blue costume with a scarlet collar and a dark brown hat. While denying the charges, she broke down in tears, wiping them away with a lace handkerchief. It seems that life was quite an overburden for Victoria by now, finding solace among her riches and alcohol. It was a difficult time of her life. She had to pay £35 (£2,977.16) damages but was cleared of a charge of false imprisonment which had been alleged.

But Victoria was as popular as ever on the stage and in May is expected back at the Preston Hippodrome where she is ever welcomed as, ‘there is only one Victoria Monks, the chic, the charming and the daring…..There is spice in her songs, and brilliance in her execution, that are never short of absolute genius.’ Perhaps the correspondent who wrote this was promoting the theatre and knew only a little of Victoria Monks as he (presumably he) claims to prefer her to her sister Marie. While Victoria doesn’t have a sister called Marie, he might be referring to Marie Loftus whose daughter was Cissie Loftus, with a Blackpool connection, and the two were often confused, the one for the other, which was taken as great compliment by the mother no doubt.

In 1921 Victoria was involved in another, rather unsavoury, court case in which she was accused of ‘stealing and receiving’ a dressing case containing valuable items, including diamonds, and pawning the proceeds. It was a period of her life in which she had been very unwell and the man she was living with, Captain Arthur Simmonds and who eventually pleaded guilty, turned out to be a conman who had claimed to be the son of a Canadian millionaire. She claims she wasn’t aware that the expensive items that he had given her had in fact been stolen. The contradictions in the statements that she had given to the police were due to a severe case of consumption (TB) when the doctor had virtually given up on her. Again, she broke down in court and the proceedings had to be interrupted. She had had to give up several engagements because of her illness and had had to pawn jewellery to keep herself financially buoyant. When working she would earn £100 – £135 (£4,050.55 – £5,468.25) a week. When not working of course, she had no income at all.

Simmonds, (real name reported as Stephen Penge) who was actually born in the East End and was the son of an offal dealer, was given 18 months hard labour for the theft of the dressing case and 5 years penal servitude. She had met ‘Captain’ Simmonds at the Victory Ball so must have been associated with him for a couple of years. In 1921, her court appearances were well known and made good substance for journalism. Maybe she genuinely thought it was a gift from her man friend or maybe it was in her character not to believe the worst, and that if she could get away with it, her innocence in the affair would stay intact. The prosecuting counsel didn’t think so and assumed that she would have been well aware of the property being misplaced and having been lost by someone, and thus belonged to them, and had told ‘lie upon lie’ when interviewed by the police in Birkenhead. It led the counsel, Mr Travers Humphreys to that phrase ‘that the evidence reveals a sordid, miserable story of drunkenness and debauchery.

As the evidence was given at the Old Bailey, the jewellery in question, worth around £1,500, (£60,758.31) had been found in a taxi and which had been left there by the careless or unfortunate porter of the hotel where a Mrs Price Hughes had come to town to stay. Ultimately Alfred Simmonds would plead guilty to theft by finding rather than by theft alone. The jewellery had subsequently been pawned which is probably how it was traced and Victoria was found wearing some of it while she was performing at the Argyle Theatre Birkenhead in the November of 1920. At Birkenhead, Simmonds had claimed he had bought the jewellery in London’s East End and ‘Miss’ Monks had nothing to do with it. By January, the police denied that they had had her in custody after her performance at the Birkenhead theatre but the story unfolds as the case came to trial at the Old Bailey as a ‘tale of drink and debauchery’ on the parts of the two accused.

Victoria Monks at the time lived with Alfred Simmonds at her rented flat in Garrick Street in London. It is not certain how much guilt can be attributed to Victoria herself as it was the man Simmonds who ultimately took the blame for it.

Victoria perhaps had a genuine excuse, of the deception regarding the jewellery while she was staying at Shoreham, a seaside resort which many entertainers favoured and made popular. Her son Karl was staying there with her and had been given an envelope by Simmonds, it seems, containing a sum of money, probably a large sum, to take up to London. In a state of illness described as consumption, for which the open seaside air would be beneficial, Victoria had no idea of the content of the envelope, nor did Karl in his evidence in court. Victoria claimed that she didn’t even know that her son Karl was going off to London.